Broad Search

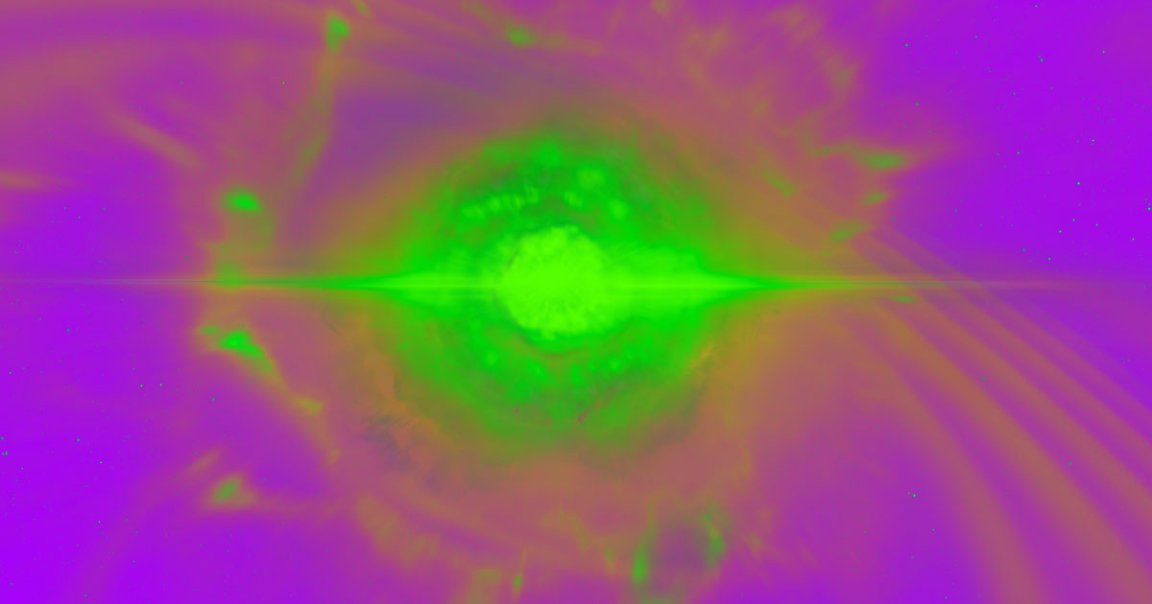

When the European Space Agency launches its Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), which is a network of satellites built to detect faint ripples of gravitational waves given off by merging black holes, it may also discover thousands of new exoplanets.

Right now, all of the 4,000-ish exoplanets that astronomers have found are found in close proximity to our solar system — the farthest is just 27,700 light-years away. But when LISA launches in 2034, it will be far more sensitive than any existing exoplanet-spotting tool, according to Scientific American. In fact, it could potentially spot exoplanets not only throughout the entirety of our own Milky Way but in neighboring galaxies as well.

Prime Candidates

But there are some caveats. Specifically, LISA will only be able to detect exoplanets that are at least 50 times the mass of Earth — and which orbit a particular kind of binary star system, according to research published Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy.

As the binary stars orbit around each other, their center of mass is thrown off by the gravity of any exoplanets orbiting along with them. That back-and-forth wobble of the star system’s central point creates rippling waves that LISA would be able to spot.

That also means, per SciAm, that the satellite network won’t be able to find exoplanets that orbit solitary stars — nor will it be able to tell whether any of these alien worlds are actually habitable.

READ MORE: Future Gravitational Wave Detectors Could Find Exoplanets, Too [Scientific American]

More on gravitational waves: Scientists Just Detected a Black Hole Devouring a Neutron Star