Sucking It Up

One of the inventors of CRISPR gene editing, a groundbreaking new method to engineer genetic code, believes we could use the same techniques to tackle some of the biggest issues facing humanity right now, including climate change.

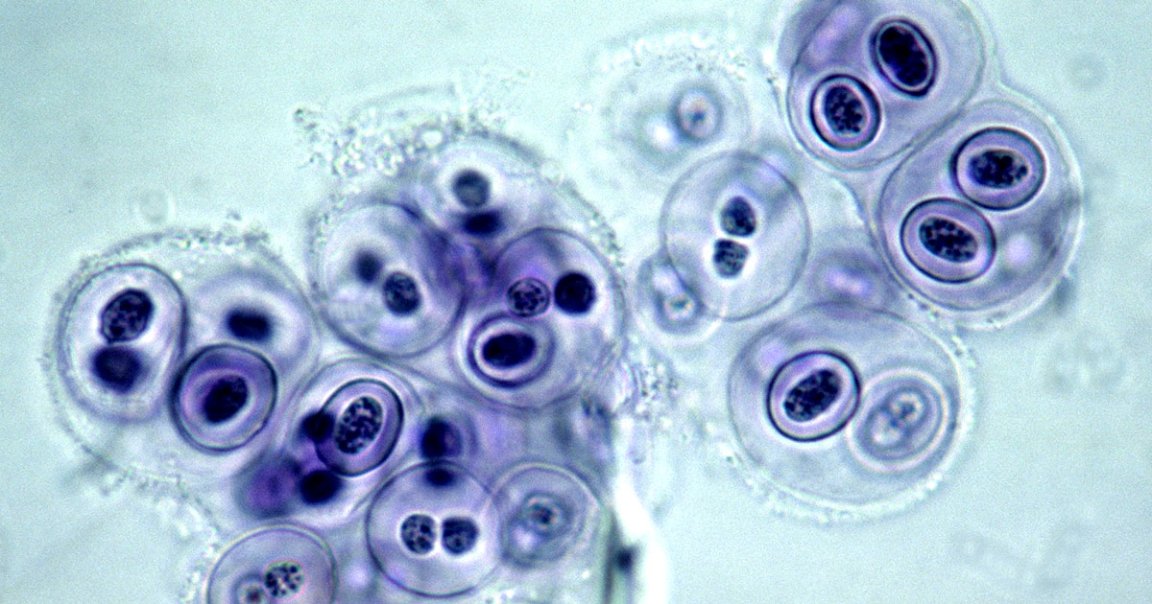

In a new interview with MIT Technology Review, Jennifer Doudna, who received a 2020 Nobel Prize alongside colleague Emmanuelle Charpentier for the discovery, said that CRISPR can be used to “enhance” the ability of microbial communities in the soil or water “for carbon capture.”

The futuristic idea is “potentially high impact” but also “farther out,” according to Doudna.

“There’s been a lot of focus on clinical medical uses of CRISPR,” she told MIT Tech. “However, I suspect that over the next decade, when we think about global impact and impact on daily lives, that’s where the uses in agriculture and even to address climate change will potentially have a much broader impact.”

Enhanced Resistance

The idea of using CRISPR to genetically enhance plants’ ability to suck up carbon dioxide has been around for at least a couple of years. For instance, The Salk Institute for Biological Studies’ Harnessing Plants Initiative is attempting to amplify plants’ root systems and production of suberin, their protective shell responsible for storing carbon dioxide.

Similar processes could be used to allow living organisms to store more carbon dioxide as well.

In addition to allowing plants to store more carbon dioxide, CRISPR could also allow them to become more adaptable to a climate-disrupted future.

For instance, scientists at the University of California Berkeley are attempting to modify the genetics of rice, a major source of calories for humans around the globe, to be more resistant to droughts. The research is affiliated with Innovative Genomics Institute, which was founded by Doudna. But the research is still in its very early stages.

“This is all very blue-sky at the present time,” Jill Banfield, a University of California at Berkeley ecosystem scientist and one of Doudna’s closest collaborators, told TIME in January. “First, we want to understand the pieces and how they fit together.”

CRISPR is already proving extremely versatile, and while scientists are excited most of all for its clinical applications, its potentially groundbreaking effects on the global food chain and our efforts to tackle a growing climate crisis shouldn’t be underestimated.

READ MORE: The scientist who co-created CRISPR isn’t ruling out engineered babies someday [MIT Technology Review]

More on CRISPR: Scientist Who Genetically Modified Human Babies Released From Prison