Long before The Jetsons showed an average joe flying to work in a flying car, people dreamt of a flying car for the masses. But even today, that dream is still in its infancy. There is a lot of work to be done until the modern world is ready for mass-produced, affordable, airborne cars…and it’s not hard to see why.

Technological constraints have made it nearly impossible for the flying car to become a reality—but not totally impossible. Whether it’s the careful balancing act of weight and energy consumption (see: drones) or the obvious safety concerns of untrained pilots taking to the sky, flying cars have yet to become a viable mode of transport.

To fully appreciate how difficult it is to get the flying car off the ground, and understand where we are in relation to development, here’s a look at where we are headed, and a look at some of the cornerstone inventions that brought us to where we are today.

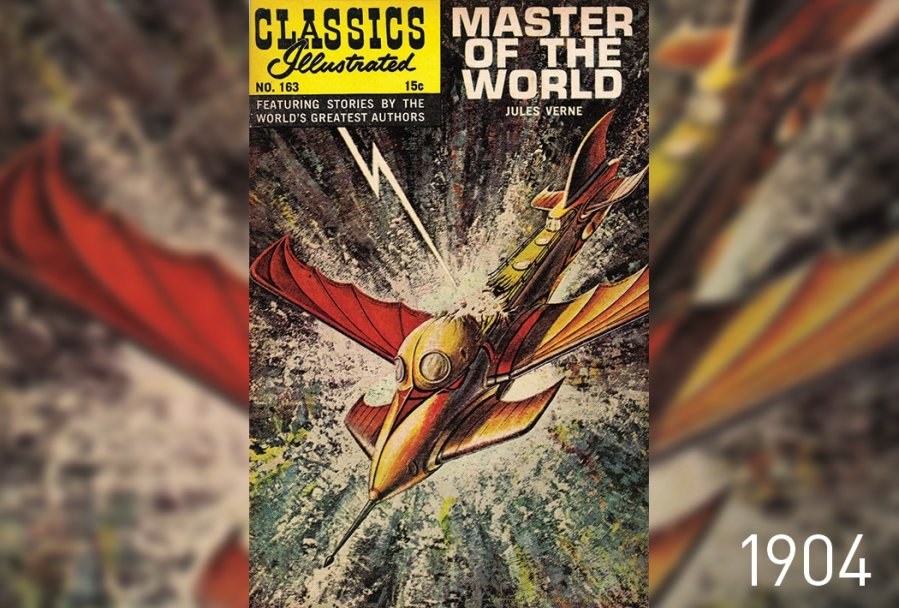

1904 – Jules Verne’s “Terror”

Source: verniana.org

One of the first examples of the flying car can be found in one of French author, and grandfather of science fiction, Jules Verne’s last novels, Master of the World. The protagonist of the novel, a brilliant inventor, creates “the Terror”—a 30-foot-long vehicle that is not only a car and a plane, but is amphibious as well.

1917 – The Curtiss Autoplane

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of the earliest real-world attempts at making a car fly came only thirteen years later. Aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss built a prototype of a flying automobile: the triplane Curtiss Autoplane, which offered space for three passengers: The pilot in the front and two passengers in the rear. Its 100 horsepower engine was able to lift it off the ground, but it was never able to take off during test flights. The project was cut short when the United States entered World War I.

1946 – The Fulton Airphibian

Credit: Bernard Hoffman/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Image

Designed by Robert Edison Fulton Jr., this six-cylinder aircraft featured a car-grade suspension and easily removable wings. The idea of an easily converted “airphibian” flying car became an overwhelmingly popular one with the public, paving the road for countless future (yet fruitless) attempts at being the first true flying car of the masses. Financial concerns resulted in it never leaving the prototype stage.

1947 – Henry Dreyfuss Convaircar

Credit: FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

What if the flying car was just a regular car, with a specialized removable airplane attachment that gave it wings? The 35-foot wide (10.6 meter) aircraft engine attachment could be removed from the roof of the four-seat car body and towed while on the ground. The, almost comically simple, idea ended in disaster when its first test pilot fatally crashed.

1957 – Piasecki VZ-8 Airgeep

Credit: avionslegendaires.net

The military also showed interest in the growing phenomenon of the flying car, even though its usefulness was yet to be proven. The US Army tasked three auto-pioneers with developing a “flying jeep” that would operate close to the ground but could traverse difficult terrain by flying over it. The ducted-fan design of American engineer Piasecki won, but it was later deemed unfit for modern combat.

1980s – The Boeing Sky Commuter

Credit: Barrett-Jackson Auction Company

This futuristic design by aerospace giant Boeing from the 1980s has all the hallmarks of what we imagine when we think of a flying car: A sleek aerodynamic chassis, vertical takeoff and landing, a roomy interior, and a compact shell. It was a significant step away from the limitations of a convertible flying car; an all-in-one vehicle that didn’t require the attachment or removal of wings or even a runway. The Sky Commuter project died before it could be fully realized, as the project costs ballooned to $6 million—a price tag far too high for Boeing at the time.

Ongoing – The Moller Skycar

Credit: Moller International

Moller International has specialized in personal, vertical landing and takeoff vehicles for more than fifty years and is still working to make the flying car a reality. Even with state-of-the-art computer technology (and with not insignificant support from investors), the Moller Skycar has yet to fly without external help. Moller International has continued to research and develop new flying car technology.

Present – PAL-V One

The PAL-V One (“Personal Air and Land Vehicle”) strips the chassis down significantly by focusing on a three-wheeled car design. It features a propeller and rotor on the roof that allows it to take off like a helicopter, while the relatively large wheels and the fact it leans into curves enable it to be driven like a motorcycle. The company is planning to open the very first flying car school and to deliver the first units next year.

Future – Project Vahana

Credit: Project Vahana

Airbus released its plans for the “future of urban mobility” earlier this year. Dubbed “Project Vahana,” Airbus has been working on a flying car concept that takes a page out of recent developments in drone technology. The current iteration of the not-yet-realized concept features an “eight fan tilt-wing” design, hoping to “improve cruise aerodynamics” and lower energy requirements.

2018 – AeroMobil

Credit: AeroMobil

Modernizing the concept of foldaway wings, Slovak flying car developer AeroMobil is attempting to take to the skies with the use of regular gasoline. It only requires a couple of hundred feet of paved or unpaved surface for takeoff and landing. The project proved it had legs (or wings) in 2013 and 2014 with two successful flights, but endured a setback when the third iteration of the prototype crashed during a test flight. The team hopes to take the AeroMobil to market as early as 2018.

2027 – Xplorair PX200

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Another example of an ongoing vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft project is the French Armed Forces funded Xplorair PX200. Announced in 2007, the project aims to say “goodbye” to conventional “rotating aerofoils,” such as the ones found in the AeroMobil, and to replace them with small jet engines, fitted inside the wing. To further set it apart, the jet engine relies on a uniquely developed thermoreactor that is more compact and produces more thrust than conventional jet engines. The project aims to commercialize the Xplorair in 2027.