Stanford’s Moral Pickle

When bioengineering students sit down to take their final exams for Stanford University, they are faced with a moral dilemma, as well as a series of grueling technical questions that are designed to sort the intellectual wheat from the less competent chaff:

If you and your future partner are planning to have kids, would you start saving money for college tuition, or for printing the genome of your offspring?

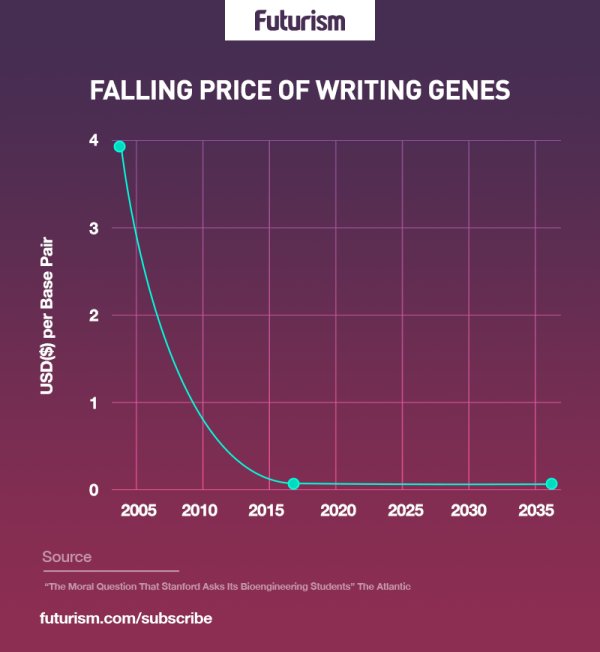

The question is a follow up to “At what point will the cost of printing DNA to create a human equal the cost of teaching a student in Stanford?” Both questions refer to the very real possibility that it may soon be in the realm of affordability to print off whatever stretch of DNA you so desire, using genetic sequencing and a machine capable of synthesizing the four building blocks of DNA — A, C, G, and T — into whatever order you desire.

The answer to the time question, by the way, is 19 years, given that the cost of tuition at Stanford remains at $50,000 and the price of genetic printing continues the 200-fold decrease that has occurred over the last 14 years. Precursory work has already been performed; a team lead by Craig Venter created the simplest life form ever known last year.

The Ethics of Changing DNA

Stanford’s moral question, though, is a little trickier. The question is part of a larger conundrum concerning humans interfering with their own biology; since the technology is developing so quickly, the issue is no longer whether we can or can’t, but whether we should or shouldn’t. The debate has two prongs: gene editing and life printing.

With the explosion of CRISPR technology — many studies are due to start this year — the ability to edit our genetic makeup will arrive soon. But how much should we manipulate our own genes? Should the technology be a reparative one, reserved for making sick humans healthy again, or should it be used to augment our current physical restrictions, making us bigger, faster, stronger, and smarter?

The question of printing life is similar in some respects; rather than altering organisms to have the desired genetic characteristics, we could print and culture them instead — billions have already been invested. However, there is the additional issue of “playing God” by sidestepping the methods of our reproduction that have existed since the beginning of life. Even if the ethical issue of creation was answered adequately, there are the further questions of who has the right to design life, what the regulations would be, and the potential restrictions on the technology based on cost; if it’s too pricey, gene editing could be reserved only for the rich.

It is vital to discuss the ethics of gene editing in order to ensure that the technology is not abused in the future. Stanford’s question is praiseworthy because it makes today’s students, who will most likely be spearheading the technology’s developments, think about the consequences of their work.