A team of engineers at the University of San Diego have come up with a futuristic skin patch that can not only track a wearer’s blood pressure and heart rate but even levels of glucose, alcohol, and caffeine.

The team claims it’s the first all-in-one patch to both monitor cardiovascular signals as well as several biochemical levels in the blood.

“This type of wearable would be very helpful for people with underlying medical conditions to monitor their own health on a regular basis,” Lu Yin, co-author of the accompanying paper, published in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering this week, said in a statement.

“It would also serve as a great tool for remote patient monitoring, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic when people are minimizing in-person visits to the clinic,” Yin added.

For instance, the health-monitoring patch could allow diabetics to continuously monitor glucose levels in their blood, or detect sepsis, a highly dangerous condition in which the body turns on its own tissue as a result of an infection.

Another great benefit to the technology is that it doesn’t require a health worker to insert a catheter into one of the patient’s arteries, something that’s currently necessary in order to continuously monitor blood pressure and other vital signs.

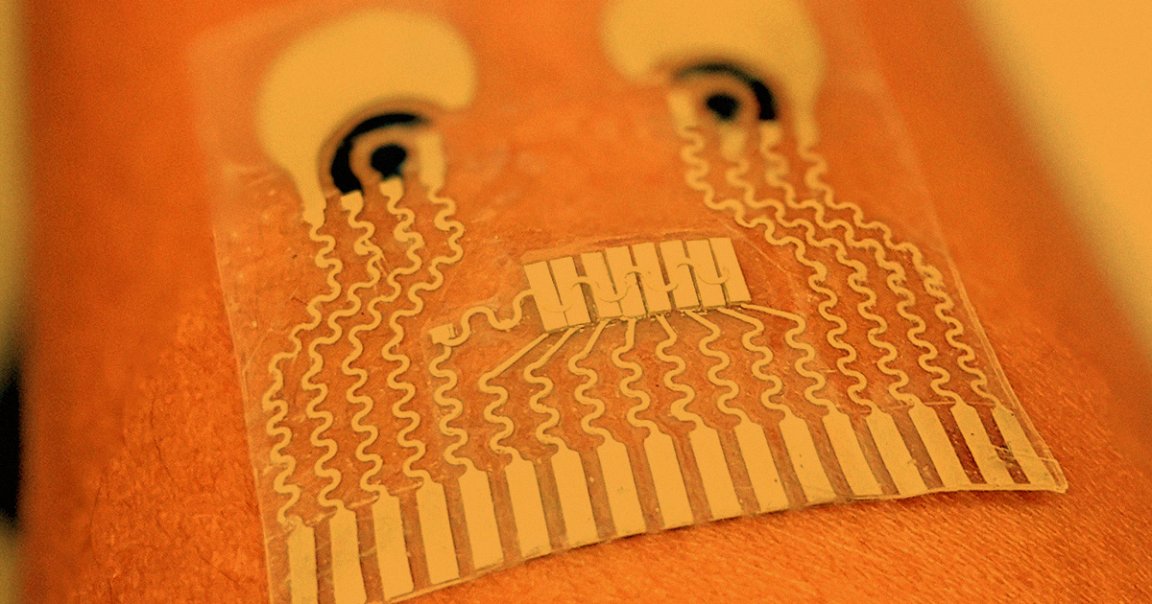

“The novelty here is that we take completely different sensors and merge them together on a single small platform as small as a stamp,” Joseph Wang, UC San Diego professor and co-author of the study, said. “We can collect so much information with this one wearable and do so in a non-invasive way, without causing discomfort or interruptions to daily activity.”

Small ultrasound transducers integrated in the patch are capable of detecting blood pressure by bouncing off ultrasound waves off of an artery. The chemical sensors work by releasing a substance called pilocarpine into the skin to make it sweat. The sensors then tests the sweat for the presence of several chemical substances.

Being able to read a number of different parameters at once would give health practitioners are far more extensive view of a patient’s health.

“Let’s say you are monitoring your blood pressure, and you see spikes during the day and think that something is wrong,” co-author Juliane Sempionatto, PhD student, said in the statement. “But a biomarker reading could tell you if those spikes were due to an intake of alcohol or caffeine. This combination of sensors can give you that type of information.”

The team is already working on an even more capable patch with even more sensors. These new sensors could “monitor other biomarkers associated with various diseases,” according to Sempionatto.

So far, the patch needs to be wired up to an external battery and an external monitor to display readings. The team, however, is hoping to include both a power source and a display in an upcoming “fully wearable” version.