NASA revealed findings earlier this month that strongly supported the idea that Mars was once a wet, tropical world with the potential to host many kinds of complex life forms. Solar winds had stripped Mars of its atmosphere over billions of years, resulting in the dry, red planet we know today, right?

Now scientists aren’t so sure.

The Red Desert

New research published earlier this week by scientists at the California Institute of Technology and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory suggests Mars never actually had a dense atmosphere to strip away.

Currently, scientists believe that a planet needs a thick atmosphere consisting of enough carbon dioxide to host liquid water. This greenhouse gas is used to trap enough heat and engender a surface pressure that keeps the water there.

Ehlmann reasons that Mars had an atmosphere, just not a thick one. It was just thick enough to keep liquid water on the surface from immediately evaporating, but it didn’t contain as much carbon dioxide as scientists previously thought. So the carbon didn’t go anywhere. It just wasn’t there to begin with.

“The jury is still out on how extensive an ocean there may have been, if it ever existed,” says Bethany Ehlmann, a planetary scientist at Caltech and the JPL and a coauthor of the new study. “But the new data clarifies for climate modelers, who have to explain why these lakes could persist, what the plausible atmospheric conditions are. It’s a slight adjustment in our thinking of what early Mars might have looked like.”

Ehlmann thinks extreme Earth environments like the southwest deserts of North America or the polar deserts of Antarctica — which still do contain standing bodies of water — are better comparisons to what Mars would have looked like in its past.

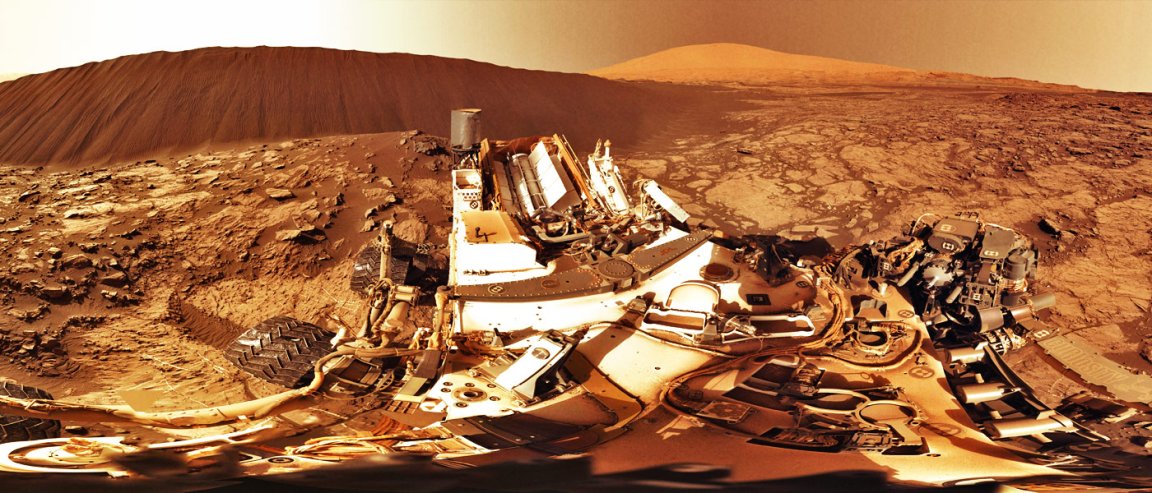

However, Behlmann does emphasize that the new paper is “fundamentally a modeling study.” Data was collected from various instruments and missions, including ground-based work involving isotope analysis of carbonate in meteorites, remote sensing operations of rocks on Mars, and most recently information gathered by the Sample Analysis at Mars instrument on the Curiosity rover, capable of conducting some basic onboard chemical analysis of rock samples.

All of this information was plugged into computer models, which reasoned that the current geological state of Mars is only best explained if the atmosphere used to be at moderate levels, in which carbon compounds in the air dwindled away slowly rather than being sharply shaved off.

This would help explain why carbon deposits in the Martian atmosphere are lower than expected.

Life on Mars

The results seem to be a discouraging answer to anyone who hoped to find evidence of past or current life on Mars. However, the researchers aren’t ready to make any definitive conclusions. “The best thing, ideally, would be to get on the ground and measure the actual isotope value of carbonate,” says Ehlmann.

Unfortunately, we’re a long way from just sending a human being up to Mars for the afternoon to get some samples. The Mars 2020 rover will be capable of collecting sample that can be sent back to Earth, but that mission doesn’t launch for another five years.

The key to verifying the results could be using the MAVEN space probe, a tool that was crucial in helping NASA scientists determine how Mars lost its atmosphere in the first place.

“As MAVEN continues to make measurements over the next year, it’s going to be really important to pin down more details on the loss rates of the carbon and oxygen species. MAVEN has the ability to constrain those.” Ehlmann says.

Moving forward, Ehlmann hopes the new paper will help highlight the importance of studying isotopes in future geological and atmospheric research of Mars, as well as how useful it is to couple different sources of data together to make conjectures about planetary science.

“It’s the key to really nailing the question of the evolution of habitable environments on Earth versus Mars,” says Ehlmann.