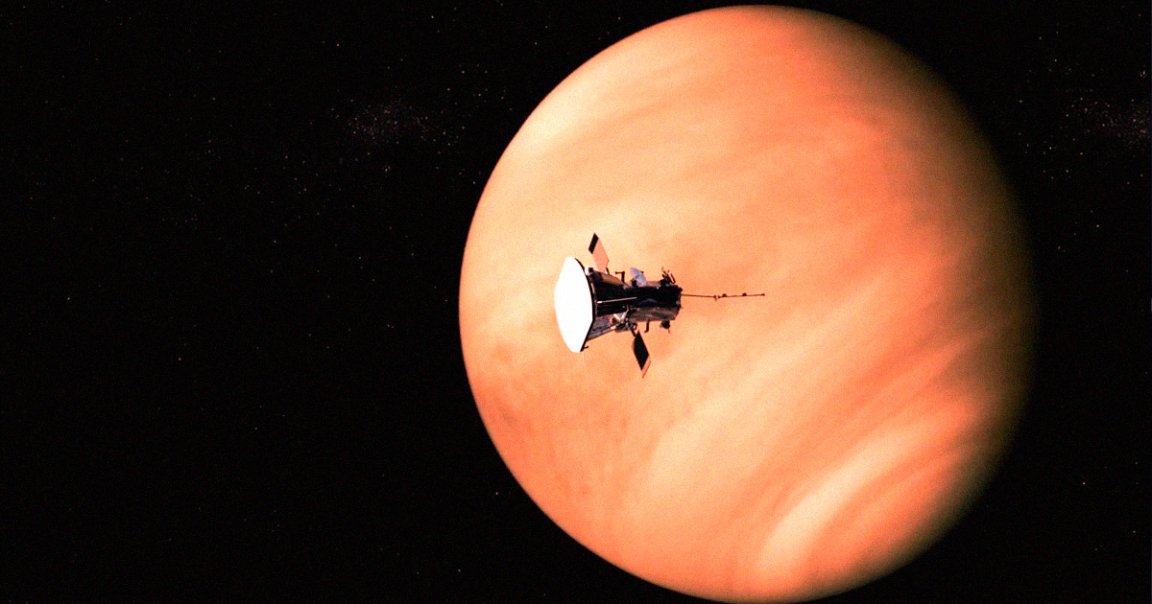

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe came very close to Venus during its flyby in July 2020.

In fact, after scientists sifted through all the invaluable data it collected during its trip, they found that the tiny probe actually made it inside of the far reaches of the hot planet’s extremely dense atmosphere.

The probe got so close — just 517 miles from the surface — that it picked up what appear to be natural radio emissions, as detailed in a paper published this week in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The researchers are hoping to use the data to gain new insights into how Venus devolved into a swirling ball of hot gases, despite its similar size and structure to Earth. Its hostile environment makes it exceedingly difficult to study, making any glimpses we get even more exciting.

The results of the new research show how the planet’s atmosphere changes over the Sun’s 11-year-long activity cycle. The Sun’s magnetic field completely flips on its head every 11 years, causing its north and south poles to switch.

The powerful activities on the Sun’s surface also increase throughout the cycle, with effects being felt all the way back on Earth, including auroras or disruptions to radio communications.

One of the Parker probe’s scientific instruments, called FIELDS, picked up seven minutes worth of natural, low-frequency radio signals during its flyby of Venus’ ionosphere, the region of a celestial object’s upper atmosphere that gets ionized by the Sun’s radiation.

“I was just so excited to have new data from Venus,” NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s Glyn Gollison, lead author of the paper, said in a statement. “Then the next day, I woke up,” he added. “And I thought, ‘Oh my god, I know what this is!'”

Gollison recognized the signals from the ones that were collected by NASA’s Galileo orbiter, which flew by Jupiter and its moons and ended its mission back in 2003. The natural radio emissions from Venus were surprisingly similar to the signals detected as Galileo flew through the ionosphere of Jupiter’s moons.

Gollison and his team compared the emissions picked up by Parker last summer to the last available data on Venus’ ionosphere — readings by NASA’s Pioneer Venus Orbiter collected in 1992 almost 30 years ago.

Back then, the Sun’s solar cycle was at its maximum. Now, with the Parker Solar Probe’s observations, we can compare the readings to just six months after the latest solar minimum, or the least active part of the solar cycle.

The surprising conclusion: Venus’ ionosphere thins out just as the solar cycle reaches its minimum, echoing the effect.

“When multiple missions are confirming the same result, one after the other, that gives you a lot of confidence that the thinning is real,” said Robin Ramstad, co-author and researcher at the Laboratory of Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado, Boulder, in the statement.

It’s the culmination of decades of data collection. While Parker’s primary objective is to get close to the Sun, its many flybys of the other planets in our Solar System show that there are plenty of mysteries to still be uncovered in the data it gathered.

READ MORE: NASA’s Parker Solar Probe Discovers Natural Radio Emission in Venus’ Atmosphere [NASA]

More on Venus: NASA Funds Spacecraft “Swarm” to Explore Venus