Forgotten Food

It’s a problem of leviathan proportions: every year, an amount of food equivalent to roughly 9,553 blue whales — the largest animal that has ever lived — gets thrown in the garbage. (That’s 1.3 billion tonnes, or 2.9 trillion pounds.)

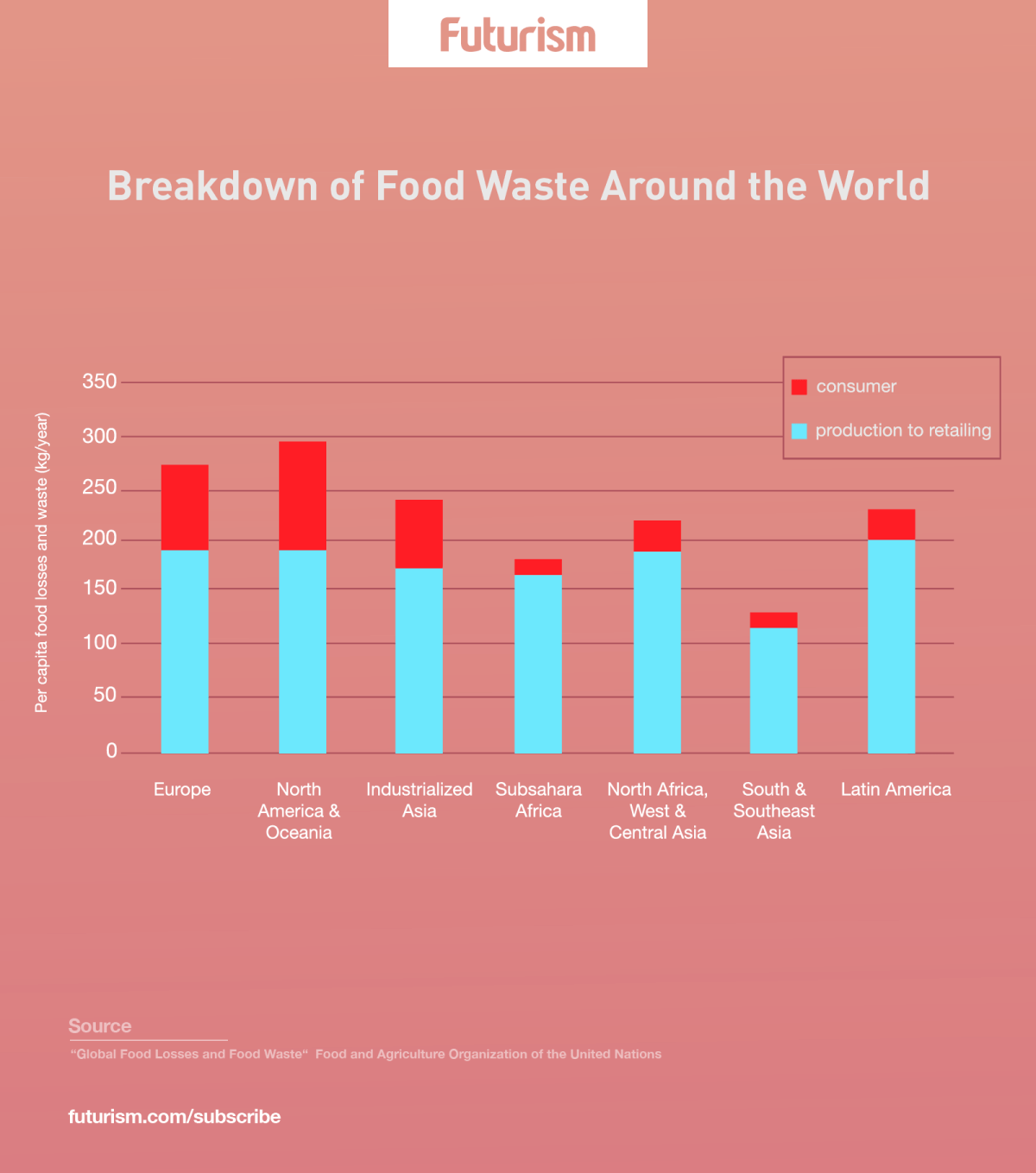

According to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, as much as one third of all food is wasted before it can be eaten, either by food loss (spilled or spoiled before reaching a store) or food waste (when it gets thrown away or spoils before use).

Food production is already an environmentally costly process: it depletes nutrients and helpful organisms from the soil, adds pesticides and algal-bloom-causing nitrogen to nearby water sources, accounts for 69% of all water use worldwide, and produces greenhouse gases. In fact, agriculture is second only to energy in producing the most planet-warming carbon dioxide and methane worldwide.

Add in the impact of food waste, and the footprint of food production becomes dizzying. The FAO estimates the cost of wasted food is equal to about US $750 billion every year — and that doesn’t take into account costs that can’t be calculated, like impacts on biodiversity and shortages that feed social conflict. In the below video, FAO estimates that nature could charge us at least an additional $700 billion for these hidden side-effects.

However, entrepreneurs all over the world are stepping up to the plate to address food waste in remarkably creative ways.

Barnana produces snacks from dehydrated bananas, sourced from Latin America, that would have been otherwise wasted — either because they’re scuffed, too ripe, or an unappealing size for consumption. The company has even “close(d) the banana waste loop,” as chief marketing officer Nik Ingersoll told Forbes, by powering their dehydrator using pellets made from dried banana peels.

In the Netherlands, Koffiekik is growing protein-rich oyster mushrooms using discarded coffee grounds. In California, Imperfect Produce delivers produce that supermarkets won’t sell in-store, due to their odd shapes and sizes, for 30-50% below market price. Bronx-based Baldor Fresh Cuts uses food scraps from restaurants, like carrot tops and pineapple cores, to make cookies, supplements, breadcrumbs and more.

“The idea is to take an item that normally would be wasted and turn it into a consumer product,” Tom McQuillan, Baldor’s director of food service sales and sustainability, told Popular Science. “It’s a great way to get food into the hands of the food-insecure, and to people who should be eating healthy foods.”

Tipping the Scale

By turning food waste back into food, these entrepreneurs are beginning to tackle one of our planet’s biggest paradoxes: despite producing much more food than we consume, millions of people remain hungry.

According to the World Hunger Education Service, nearly 795 million people suffered from chronic undernourishment in 2014-16.

In developing regions, this impacts about 12.9% of the population, compared to less than 5% of developed countries. Unsurprisingly, the balance of food waste skews in the opposite direction, with hungrier countries producing less waste.

In these countries, food waste usually isn’t due to distaste for bumpy produce, but instead lack of access to the technology needed to keep food fresh. A 2014 study from the University of Birmingham found that India loses 4.4 billion UK pounds, or roughly US $5.8 billion, worth of fruits and vegetables due to the absence of refrigerant technology.

As such, projects are underway in these countries that seek to preserve food before it can spoil. In Kenya, where more than half of the mango crop often spoils before reaching market, Azuri Health is developing a facility to dry the mangoes into fruit leather, a shelf-stable product and dense source of nutrients.

The FAO-partnered SAVE FOOD Initiative is among the biggest organization pursuing this mission. Thirteen African countries already have SAVE FOOD initiatives underway to reduce food loss and bolster small farmers, as do India, Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Malaysia, and Timor-Leste. In January 2017, the initiative launched its first project in Russia, where food waste is lower than the global average, but still estimated, as of 2013, at roughly 56 kilos per person per year.

“If each of us takes a look at their fridge and starts counting the volume of food we throw away each year, we will end up with industrial-scale figures. This is particularly disturbing against the background of the large numbers of people around us who have to save on the essentials and need help,” said Viktoria Krisko, president of Foodbank Rus, at the launch.