It Feels Like the Real Thing

The placebo effect occupies a liminal space in clinical consideration, somewhere between biological and psychological, therapeutic and phony. Scientists maintain that it is a collective term for a host of processes and mechanisms that effect our experience of our condition — gymnastics of perception — rather than helping to cure the underlying, objective, and measurable causes of it.

Ted Kaptchuk, Director of the Harvard-wide Program in Placebo Studies, summarizes it as “finding out what is it that’s usually not paid attention to in medicine — the intangible that we often forget when we rely on good drugs and procedures. […] The placebo effect is a surrogate marker for everything that surrounds a pill. And that includes rituals, symbols, doctor-patient encounters.”

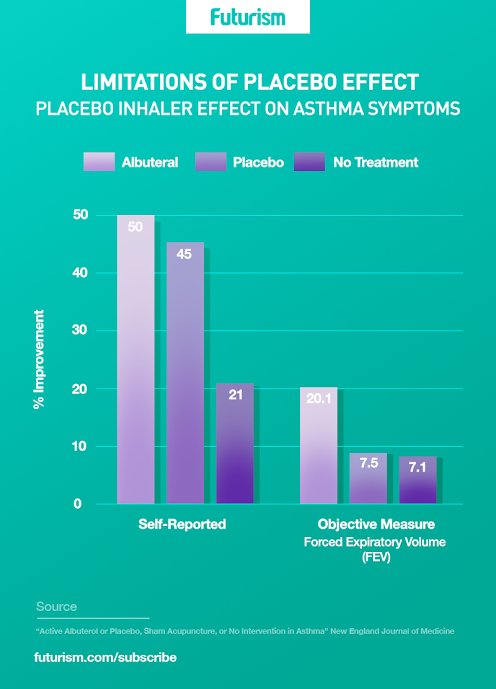

A study undertaken by Kaptchuk and colleagues that shows the power of perception over objectivity particularly well was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011. Subjects were given the effective drug albuterol, a placebo inhaler, acupuncture, and periods without treatment. They all took each treatment three times, which had the double effect of producing lots of data and allowing subjects to serve as their own controls. While everyone reported a similar level of improvement in their symptoms regardless of which treatment they had most recently undergone, objective measures indicated that only the albuterol improved airflow — but all three options actually increased their lung functionality.

While a significant amount of the placebo effect remains obscured by a lack of research, scientists have been able to discover some of the perception mechanisms behind what allows our brains to fool our bodies into feeling better.

The main cluster is the effect that conditioning has on our body’s responses — the results of a soft-Pavlovian training that has been built up since birth. The most rudimentary form of this is the power of expectation. In an interesting study, Luana Colloca has conducted experiments involving lights. One such experiment involved flashing a red light when a subject was given a high voltage electric shock and flashing a green light when they were given a lower one. She then played with the levels and eventually found that, even when the shocks were equal, when the green light flashed, subjects reported less pain. Conversely, when the red light was on, they exhibited higher pain than the shock would reasonably evoke; this is called the nocebo effect.

The essence of this is manipulated and made more complex by the very presence of clinical procedure — a real world “green light.” It can be seen most pertinently when it comes to drugs.

The body responds positively to any drug because it remembers the healing effect drugs have had on it before. This is reflected in one of the most interesting pieces of placebo research in recent years, in which participants knew they were taking sugar pills but still experienced therapeutic effects. This showed that something beneath our conscious and rational mind believed the administration of drugs was beneficial, and exhibited the positive effects of taking drugs when it received one — despite the conscious mind knowing it was fake. The action taking of a pill, rather than what was in the pill itself, became the signal to release the chemicals that the real pill normally would.

Prescribing Placebos?

The next stage in the research is to codify the precise natures and mechanisms of the placebo effect. Franklin Miller, a retired NIH bioethicist, asserts that “sooner or later we’ll get rid of the term” because it will be broken down into component parts.

If we can break it down into these parts, these precise mechanisms, it then becomes hypothetically possible to begin to use them in a therapeutic setting. Because the doctor is using the mechanisms of perception, this actually means that manipulating the placebo effect becomes a psychological treatment of biological phenomena — a psychosomatic treatment.

While Miller goes on to say that the effect can never cure an objective disease with definite biological causes — it could, for example, not cure the ebola virus, but may help with symptoms — because “There are real limits to what you can condition.” The placebo has to treat something that the brain can adjust itself, without help, such as pain.

An example of this is irritable bowel syndrome, which Kaptchuk used for an experiment. Two groups got placebo acupuncture, but half were treated with empathy by the doctor, while the other half were treated without any warmth. The half who had been treated kindly reported 15 percent more relief. Experts have also suggested using the effect to reduce America’s current opium crisis, as it could provide an effective pain relief with smaller doses of physically addictive substances being involved.

The placebo effect remains obscured by a lack of research and the enigmas and riddles of the human mind. However, what is clear is that there is huge potential for it to be a part of our medical system.