Open-Label Placebos

Clinical epidemiologist Dr. Jeremy Howick recently published a review of five research studies covering 260 patients that showed how “open-label” placebos can be an effective treatment for a number of health issues. Placebos are treatments that have no active medications in them (often they’re just “sugar pills”). So called “open-label” placebos are just like normal placebo pills except patients know they don’t contain any medication. While the belief that placebos only work when patients believe they are real medication is a commonly held one, this open-label study proves that this isn’t necessarily always the case.

In fact, this isn’t even a new phenomenon: In 2009, Wired reported an ongoing problem in the pharmaceutical industry where placebo effects in drug studies that were too strong were “ruining” the chances of drugs making it onto the market. In essence, patients were experiencing too much relief from too little actual medicine. The initial response was to search for new medicines, but researchers like Howick see a different answer: learning to use open-label placebos in new ways.

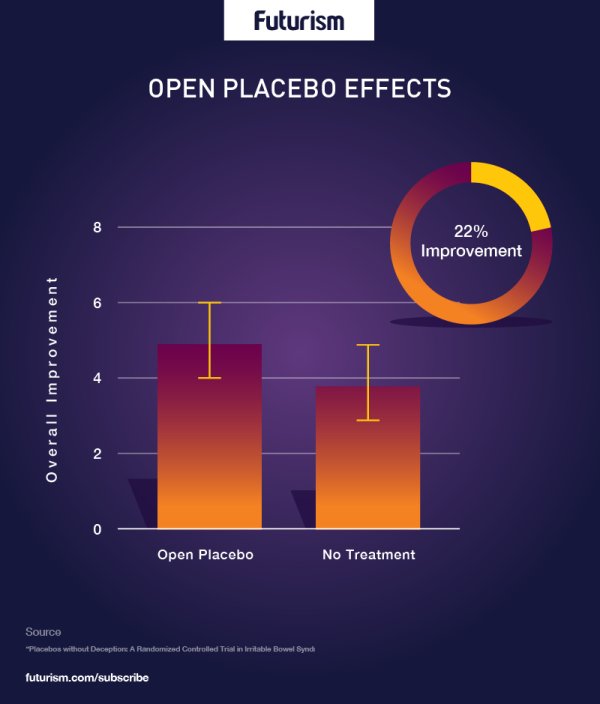

One of the studies Howick reviewed was led by Harvard Medical School’s Professor Ted Kaptchuk. Kaptchuk treated patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with either nothing or open-label placebos. To the surprise of most who read the results, many of the patients who knowingly took placebos experienced significant relief of their symptoms — including reduced pain. In fact, at least one patient who experienced a near total recovery became sick again once the study ended her access to the placebos.

Howick also reviewed studies in which patients were treated for depression, ADHD, and lower back pain — all with open-label placebos. In each case, the placebos were fairly successful.

Why Do Placebos Work?

In the open-label trials, participants clearly understood that they were either not receiving any treatment at all, or receiving placebos. And while they knew what they were getting wasn’t really medicine, previous research has shown that even placebos can cause real physiological changes. For example, they can increase both the levels of dopamine in the brain and the circulation of endorphins in the body, two occurrences associated with feeling less pain.

However, placebos aren’t always effective. Research indicates that they are more likely to be effective when patients are suffering from symptoms such as fatigue, itching, and pain—sensations that the brain can modulate and perceive differently depending on the situation. An individual person’s genetics also play a role in how effective placebos are. Specifically, research shows variants of genes that affect dopamine levels are likely to be connected to sensitivity to placebos.

Beyond the physical process, there are several hypotheses explaining why open-label placebos in particular appear to work as well as they do. One possibility is that patients might be conditioned to feel better once they are treated by doctors — regardless of what the treatment consists of — and that an accompanying boost to the neurotransmitters and endorphins are what produce the feeling of well-being associated with open-label placebos. This is, as reported in the Guardian, the same reason that Pavlov was able to train dogs to drool for a bell rather than actual food.

Another possibility is that patients know that placebos are working for others with their condition, and therefore expect that their symptoms will be relieved, too. This could cause their body and mind to release chemicals that make them feel better.

New Approaches To Healing

For researchers like Howick and Kaptchuk, these findings should be showing doctors a new way of dealing with illness. “I’m not advocating doctors handing them out like Smarties,” Howick said to the Guardian. “I do think, however, that this research is telling us we should start to recognize the benefits of doctors being realistically positive when they talk to patients.”

Kaptchuk is eager to see open-label placebos used in patient care, and commented to the Guardian, “If enough of these studies have positive results in different conditions, I hope we can convince the medical community that there’s something useful here.”