In the 1960s and ’70s, physicists Jacob Bekenstein and John Wheeler did a bit of math and determined that black holes “have no hair.”

That seemingly bizarre statement might have left some wondering whether the scientists were partaking in the drugs synonymous with the era, but they weren’t talking about hair in the traditional, stuff-on-top-of-your-head sense.

Or, well, just let us explain.

Hair is often used to describe how a person looks — he’s a blonde, she’s a brunette. But Bekenstein and Wheeler determined that black holes didn’t have that something scientists could use to describe their appearance.

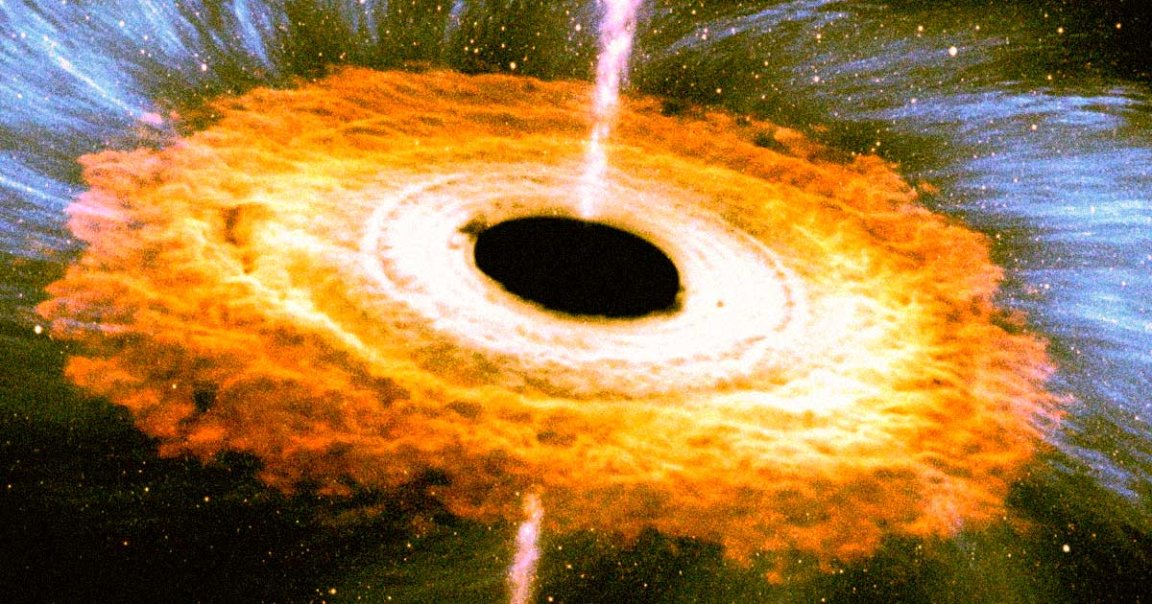

All black holes have, according to the longstanding theory, are the three observable characteristics defined by Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity: a mass, an angular momentum, and an electric charge. The black hole’s gravitational pull snatches up anything else that might be useful for differentiating one black hole from another of the same type.

In other words, the duo determined that the phenomena have “no hair” — and that makes it really hard to glean any insight into an individual black hole’s history or origin.

That changed in 2018 when a team led by University of Cambridge scientists discovered that extreme black holes, ones with the maximum electric charge possible, do have several properties researchers can use to tell them apart. But all other types of black holes remained “bald” — until now.

On November 15, a team at California’s Theiss Research published a paper in the journal Physical Review Research focused on the hair-growing ability of nearly extreme black holes.

“In the movie ‘Interstellar’ the monster black hole is nearly extreme,” researcher Lior Burko said in a press release. “We wanted to see if Gargantua has hair.”

By conducting computationally intense simulations, the team determined that two types of black holes — nearly extreme Reissner-Nordström black holes and nearly extreme Kerr black holes — can grow “hair” just like extreme black holes.

But it doesn’t last long.

“Nearly extreme black holes can pretend that they are extreme for only so long,” Burko said. “But eventually their non-extremality becomes manifest. Nearly extreme black holes that attempt to regrow hair will lose it and become bald again.”

Astrophysicists might not have to wait too long to see the “hair” on a nearly extreme black hole in real-life either.

In the early 2030s, the European Space Agency plans to launch three spacecraft as part of the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna to detect black holes’ gravitational waves — and as Burko told Live Science, there’s a chance the project could spot the “hair” on a nearly extreme one.

READ MORE: Black Holes Grow Hair, Then Go Bald Again [Live Science]

More on black holes: Baby Black Holes May Be Orbiting Supermassive Black Holes