The latest evidence suggests that Mars used to be a wet world covered in oceans, with astronomers uncovering not just icy remnants of this period, but signs of entire reservoirs of liquid water still lurking beneath the planet’s arid surface.

But we’re still far from having a complete picture of what the Martian climate looked like billions of years ago, before these oceans dried up.

Now, however, the chance discovery of pale yet unremarkable looking rocks by NASA’s Perseverance rover suggest that the Red Planet was not only wet, but much warmer than once believed, according to a new study published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

“These rocks are very different from anything we’ve seen on Mars before,” coauthor Roger Wiens, professor of Earth, atmospheric, and planetary sciences at Purdue University, said in a statement. “They’re enigmas.”

It’s a discovery long in the making. The rocks, in the form of pebbles, were actually spotted the day that the Perseverance rover landed on the planet four years ago — but scientists had so much on their plate at the time that the objects went overlooked.

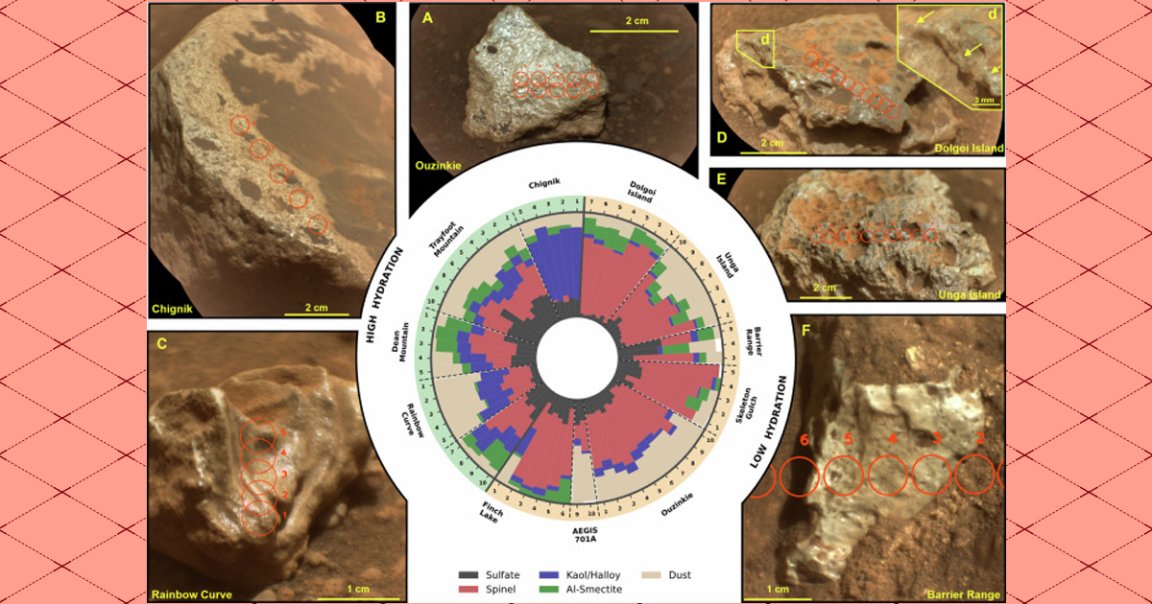

But these pale oddities just kept turning up — over 4,000 of them, in fact, the researchers said. And on a planet as unremittingly monochromatic as Mars, any deviation from the color palette could be significant. Thus, later on, when the team found larger versions of the ashen stones strewn above the bedrock in the Jezero crater, they decided to finally take a closer look.

To investigate, the team used the laser equipped on Perseverance’s SuperCam instrument, the state-of-the-art camera that forms the WALL-E looking head of the rover.

What they found was that these loose “float rocks” — so named because they come from somewhere else and not from the local bedrock — were composed of a suspiciously high amount of aluminum associated with a mineral called kaolinite. And here’s the kicker: kaolinite, along with other uncovered minerals like spinel, typically form in the kinds of warm and wet environments that microbial lifeforms thrive in.

“On Earth, these minerals form where there is intense rainfall and a warm climate or in hydrothermal systems such as hot springs. Both environments are ideal conditions for life as we know it,” Wiens explained. “These minerals are what’s left behind when rock has been in flowing water for eons. Over time, the warm water leaches away all the elements except those that are really insoluble, leaving behind what we found on Mars.”

“It’s fascinating,” Wiens added. “It’s unexpected on a cold, dry planet like Mars.” Wiens suggests that the kaolinite discovery means that “a lot of the water is still there, on Mars, bound up in the minerals.”

To follow up, the team is trying to determine where the rocks came from in order to study them “in place,” which would allow them to test how they formed.

More on Mars: Rover Discovers Evidence of Giant Ocean on Mars