Sixth Sense

Can the brain process artificial information and use it to navigate a virtual world without input from any of our five senses? Based on the results of a team of researchers from University of Washington, yes.

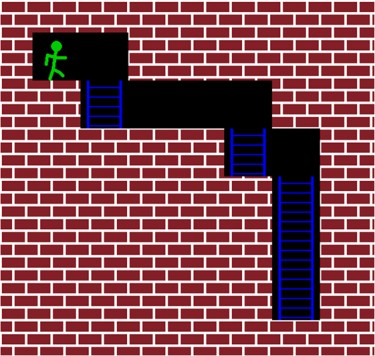

Their work shows humans playing a computer game without relying on sensory cues from sight, sound, or touch. Instead, the gamers navigate through a two-dimensional maze based on direct brain stimulation.

“The way virtual reality is done these days is through displays, headsets and goggles, but ultimately your brain is what creates your reality,” said Rajesh Rao, UW professor of Computer Science & Engineering and director of the Center for Sensorimotor Neural Engineering.

Tasked to navigate through 21 different mazes, the subjects had to move according to the direction of a phosphene-induced stimulus. Phosphene, which is perceived as light, was generated using transcranial magnetic stimulation—a technique that uses a magnetic coil placed by the skull to stimulate a specific area of the brain directly and in a non-invasive way.

With stimulation, the test subjects were able to make the right moves in the maze 92 percent of the time, versus just 15 percent without phosphene stimulation.

“We’re essentially trying to give humans a sixth sense,” adds fellow researcher Darby Losey, a 2016 UW graduate in computer science and neurobiology who now works as a staff researcher for the Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences (I-LABS).

New Way to Experience Virtual Reality

Right now, the team is working with external partners to create the company Neubay, a startup focused on commercializing the research and introducing neuroscience and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques into virtual reality and gaming.

The equipment currently used to stimulate the brain is too bulky to be carried around. Eventually however, they hope to be able to develop hardware that will make it more appropriate for real world applications. They’re also trying to develop techniques that could pave the way for more complex sensory perceptions that are difficult to replicate in augmented or virtual reality.

It’s a small, but significant, step toward greater applications in entertainment, gaming, and even medicine.

“Over the long term, this could have profound implications for assisting people with sensory deficits while also paving the way for more realistic virtual reality experiences,” ends Rao.