Ethanol-Based Cancer Treatments

Researchers from Duke University have achieved a 100 percent cure rate for squamous cell carcinoma in a hamster model by injecting an ethanol-based gel directly into tumors. The work, published in Nature Scientific Reports, was inspired by an existing low-cost therapy called ethanol ablation, and improves the method to work on a wider variety of tumors.

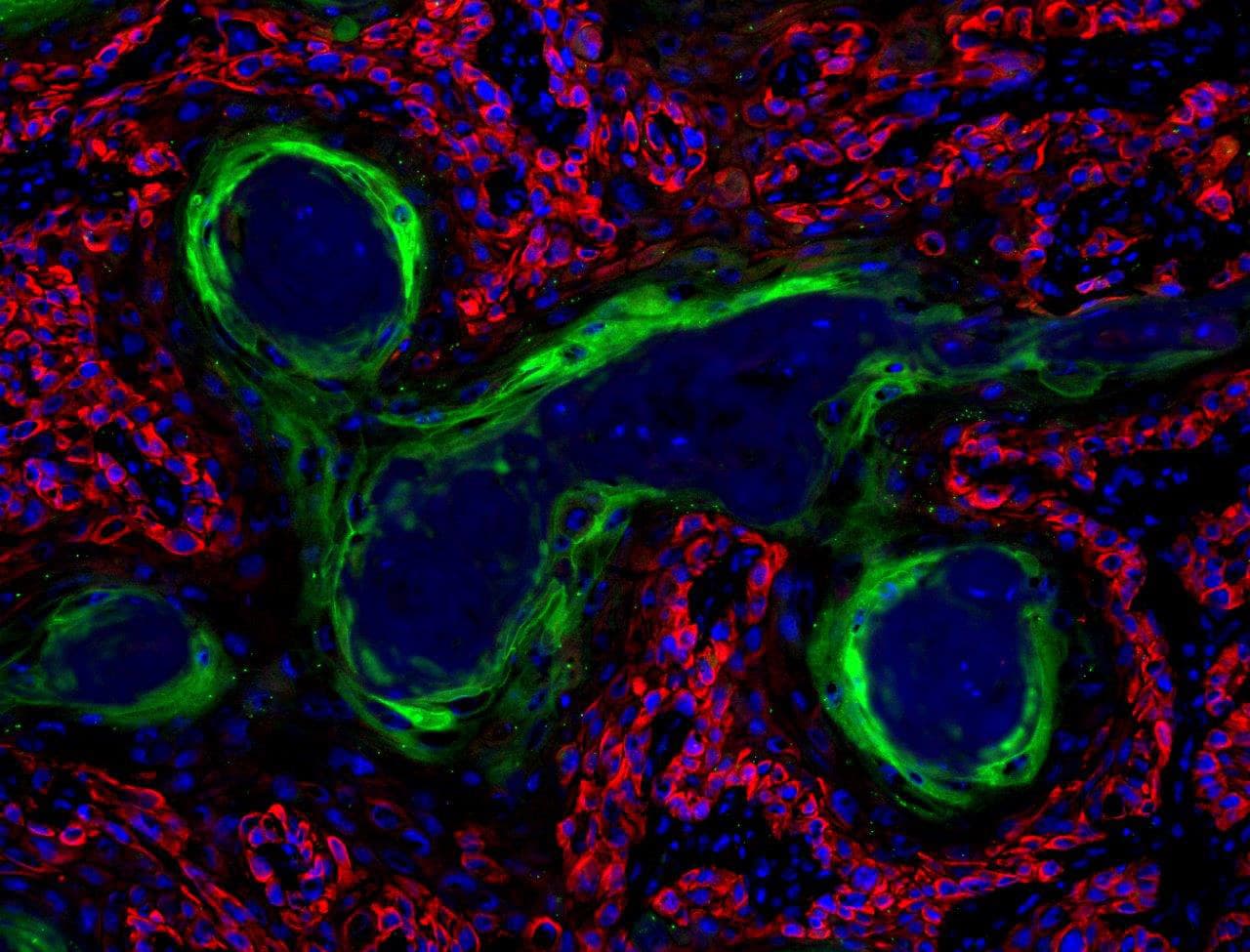

Ethanol — the kind of alcohol that makes cocktails interesting — can kill some kinds of tumors when injected because it destroys proteins and fatally dehydrates cells, in a process called ethanol ablation. Ethanol ablation is already used to treat one variety of liver cancer, with a cost of less than $5 per treatment and a success rate similar to that of surgery.

However, ethanol ablation as a treatment technique is limited. The researchers sought to improve the technique by blending ethanol with ethyl cellulose to create a solution that transforms into a gel within tumors, remaining close to the injection site.

The team trialed the gel on a hamster model: specifically, in hamsters with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Control hamsters' tumors were injected with pure ethanol, while experimental hamsters received the new ethanol gel. After seven days, 6 of 7 tumors regressed completely in the hamsters who received the ethanol gel. By the eighth day, all 7 tumors were gone, for a cure rate of 100 percent.

Cancer Treatments for Everyone

Cancer therapy is expensive everywhere, but in the developing world, it is often simply unavailable. Cutting-edge technology is in short supply in developing areas, and even healthcare professionals and electricity may not be available. This is why a person in the developing world with a cancer diagnosis is far more likely to die from it than a person in the developed world.

Most new cancer treatment research focuses on very expensive techniques, some of which may not even be economically viable in places like the United States. These new methods almost universally require sophisticated medical facilities for treatment. Simple, low-cost, non-surgical cancer treatments like the one demonstrated in the Nature study are therefore badly needed in developing areas.

The small sample sizes and animal model used in this research mean more work is required before this research goes beyond the proof-of-concept stage. Even so, the results are very promising. The team thinks even a single injection of the ethanol-based gel could cure certain kinds of tumors, and that it may be able to treat some cervical precancerous lesions and breast cancers. Perhaps most profoundly, any advances in this research will benefit patients all over the world.

Share This Article