Stuck in Place

There are several steps HIV-1 must go through in the process of infecting the body, but the most important is the invasion of an immune cell and enters its nucleus. From there, HIV-1 can take control of the cell and begin to replicate, which allows it to spread. Knowing this, one question that researchers have been asking for quite some time is, what if HIV-1 could be stopped before it makes it into a cell? Or even if the virus could be slowed down enough that the body’s immune system, and treatments that support it, had time to could get a head start on its attempts to destroy it?

A recent study conducted at Loyola University Chicago suggests this could be done, and it starts with the microtubules tracks the virus uses to get to the nucleus, as well as a protein known as bicaudal D2. The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

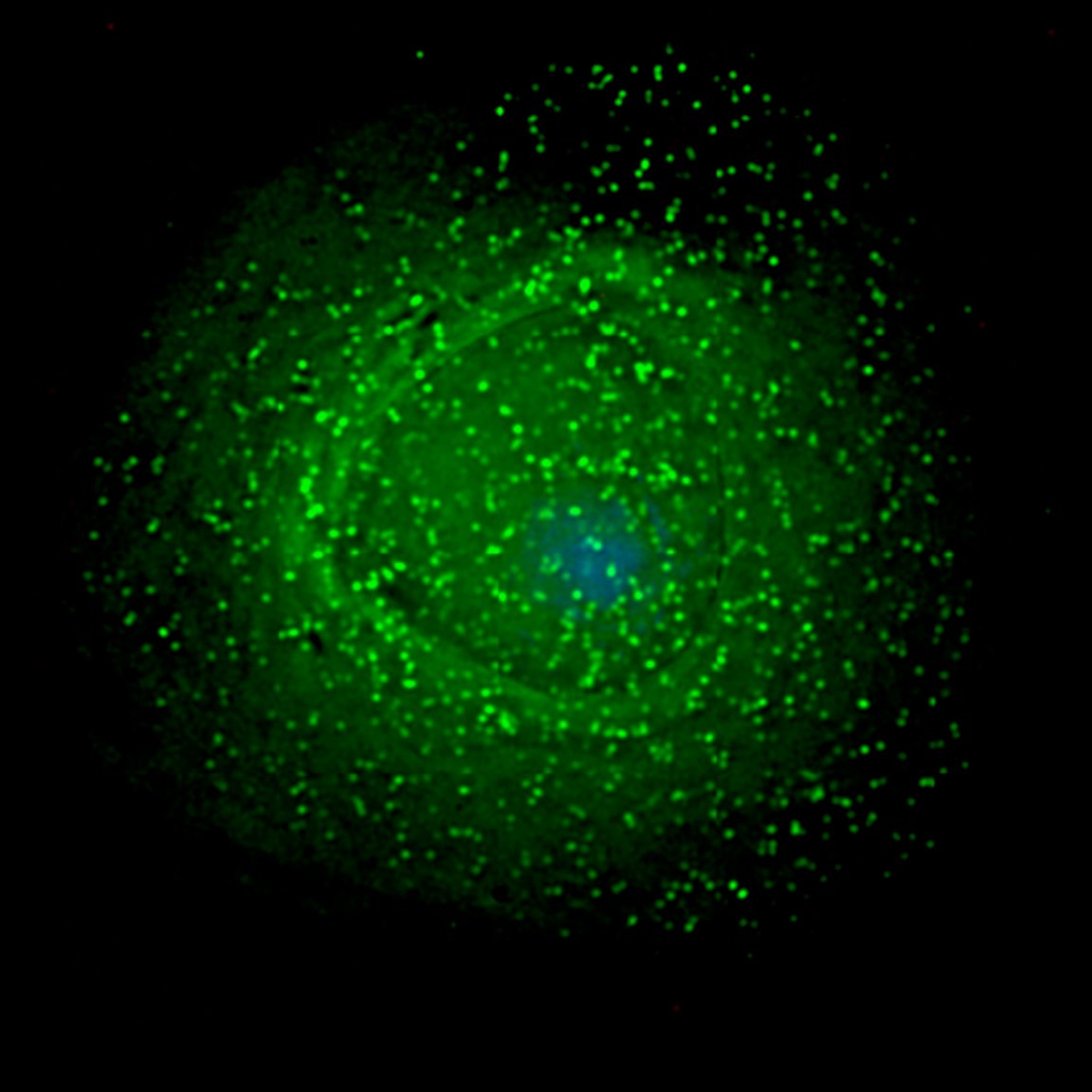

HIV-1 tends to move quickly through the body. So quickly, in fact, that it doesn’t give the body enough time to react to or even detect its presence. The virus reaches the immune cell’s nucleus by way of microtubules and attaches itself to bicaudal D2, which calls upon a molecular motor called a dynein to move along the microtubules. You could say that HIV-1 uses bicaudal D2 as a boarding pass for the biological train that will take it nonstop to its final destination within the cell: the nucleus.

That being said, if HIV-1 doesn’t have that protein, it essentially becomes stranded.

“By preventing its normal movement, we essentially turned HIV-1 into a sitting duck for cellular sensors,” explained Edward M. Campbell, Ph.D., corresponding author of the study and associate professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology of Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine.

Unwanted Exposure

The study carried out by Campbell and his team opens up the possibility of creating a drug that can prevent HIV-1 from binding to bicaudal D2. As explained by Medical Express, the introduction of such a drug would leave HIV-1 stranded in the cytoplasm — an area within the immune cell that’s thick with proteins and mitochondria. The virus must navigate through the cytoplasm to reach the nucleus, but it’s not an easy journey.

“Something the size of a virus cannot just diffuse through the cytoplasm,” said Campbell. “It would be like trying to float to the bathroom in a very crowded bar. You need to have a plan.”

Interrupting that trajectory could play a key role in future HIV treatments, or a cure. As Kristen Lanphear, Manager in Community Health Initiatives at Trillium Health, previously told Futurism, “No one tool is going to be enough to do the job because every tool doesn’t work the same for every person or every country.”

This new development is notable in that it could, theoretically, be used in combination with treatments that already exist, such as the vaccine being tested in Africa, or the antibody capable of fighting off 99 percent of HIV strains.

For the nearly 40 million people living with HIV, this research is promising. Of course, as with any new drug, the one proposed in Campbell’s study still needs more testing to determine its effectiveness and safety, particularly in terms of how it might interact with other treatments.