An almost-microscopic creature that’s sturdy enough to survive the ravages of space may hold the key to human longevity, scientists have found in new research.

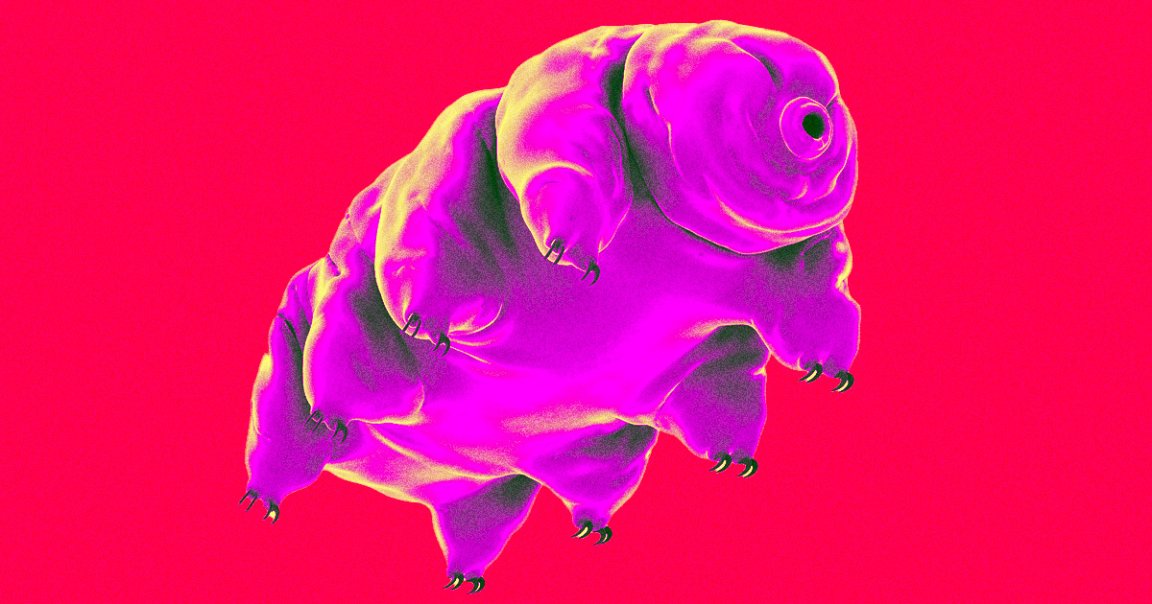

In a new study led by the University of Wyoming, an international team of researchers found that when looking into the incredible durability of the itty bitty tardigrade — known affectionately as the “water bear” or “moss piglet” — proteins from the creature might help slow aging in humans, too.

Part of what’s made tardigrades so famous is that they can survive both boiling and freezing temperatures, which was why in 2007 a team of European scientists sent 3,000 of these half-millimeter-long little guys into space, and weren’t so shocked when the majority of them survived.

When they’re threatened by temperatures, radiation, or other dangerous conditions, water bears go into a self-protective state of suspended animation known as biostasis — and it was that mechanism that interested molecular biologist and UW assistant professor Thomas Boothby, an expert in the field of tardigrades.

In the UW study, published in the journal Protein Science, the molecular biology team looked into a tardigrade protein known as CAHS D, which is key to the tiny animal’s suspended animation process. Using lab-grown human kidney cells, the scientists found that when they introduced CAHS D to the human cells, it resulted in a gel-like consistency that could help scientists better understand tardigrade biostasis — and eventually, perhaps help humans learn how to hack our own genes into performing better under stress, too.

“Amazingly, when we introduce these proteins into human cells, they gel and slow down metabolism, just like in tardigrades,” Silvia Sanchez-Martinez, a senior research scientist at UW’s molecular biology department and the lead author of the study, said in the school’s statement. “Just like tardigrades, when you put human cells that have these proteins into biostasis, they become more resistant to stresses, conferring some of the tardigrades’ abilities to the human cells.”

Fascinatingly, once the researchers removed so-called “osmotic stress” factors from the human cells, which could include dehydrating or otherwise applying harsh conditions to them, they went back to normal and the gels conferred by the tardigrade proteins disappeared.

“When the stress is relieved,” Boothby said in the UW press release, “the tardigrade gels dissolve, and the human cells return to their normal metabolism.”

While there’s certainly a long way to go before scientists figure out how to produce such biostasis effects in living humans, the findings are intriguing — and just might be a pathway to finding how to survive the harshening conditions our of dying planet.

More on cells: Scientist Who Gene-Edited Human Babies Back in the Lab Again After Prison Release