Scientists say they’ve been able to literally cut out the “bad” bits of DNA from infected cells to eliminate HIV using CRISPR gene editing.

While it’s still far too early to conclude whether the technique could be used to cure HIV, as the BBC reports — let alone whether it’s safe and effective in the long run — scientists are hopeful that gene therapy could be part of a treatment.

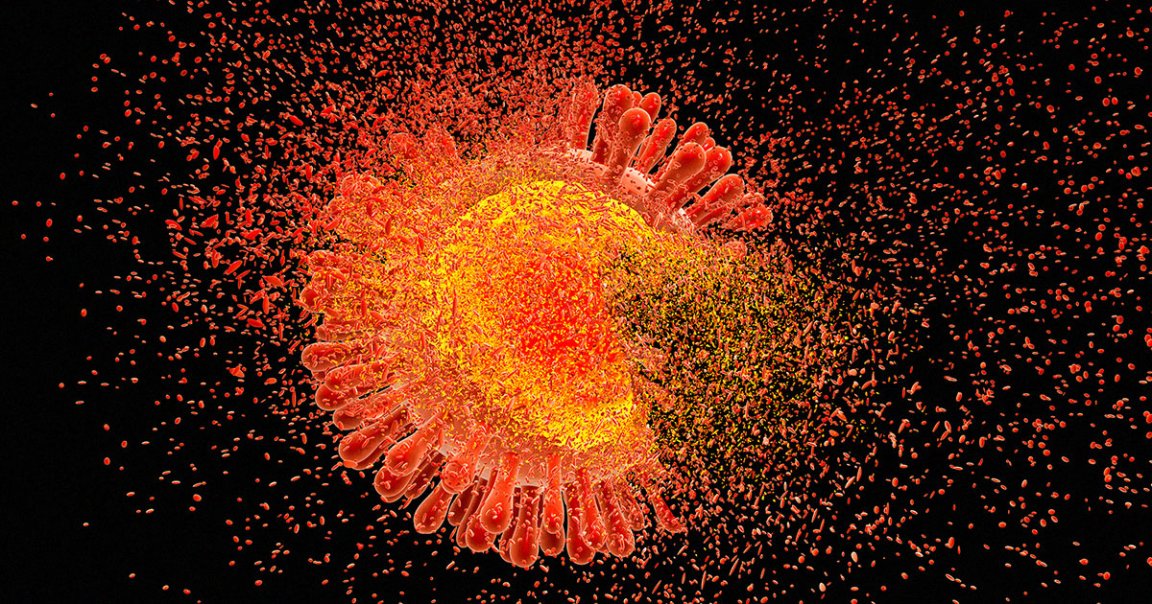

HIV, or human immunodeficiency virus, attacks the body’s immune system and has raged around the world for decades, causing untold deaths.

Despite considerable progress in the development of highly effective treatments, there still isn’t a cure.

Now, scientists at the University of Amsterdam have presented early findings of a “proof of concept” gene editing process that eliminates any trace of “dormant” HIV in cell samples.

“We have developed an efficient combinatorial CRISPR-attack on the HIV virus in various cells and the locations where it can be hidden in reservoirs, and demonstrated that therapeutics can be specifically delivered to the cells of interest,” said project lead and University of Amsterdam researcher Elena Herrera Carrillo in a statement.

“These findings represent a pivotal advancement towards designing a cure strategy,” she added.

CRISPR is a group of DNA sequences that were derived from bacteriophages. By combining them with an enzyme called Cas9, scientists are able to edit — essentially cut and paste — genes with revolutionary results, from making the human liver produce less cholesterol to restoring color vision and treating sickle cell disease.

Carrillo and her colleagues tried to address the problem of dormant HIV DNA reawakening while hiding in the human body’s immune system. Using CRISPR, they managed to disable the dormant virus in immune cells arranged on a dish.

But many questions remain. For one, cells infected with dormant HIV could lurk in other areas of the body, as New Scientist reports.

Then there’s the question of whether such a procedure would be safe in animals or humans, instead of the cell samples Carrillo’s team was working on.

“Much more work will be needed to demonstrate results in these cell assays can happen in an entire body for a future therapy,” University of Nottingham gene-therapy technologies associate professor James Dixon told the BBC.

But the proof of concept is giving researchers hope. For instance, pharmaceutical company Excision BioTherapeutics announced a new approach to use CRISPR to treat HIV late last year, though whether it’s actually effective remains unclear.

At the end of the day, the possibility of these treatments having unintended consequences could eventually slow down progress significantly.

“Off-target effects of the treatment, with possible long-term side effects, remain a concern,” Francis Crick Institute, London virus expert Jonathan Stoye told the BBC.

“It therefore seems likely that many years will elapse before any such CRISPR-based therapy becomes routine,” he added, “even assuming that it can be shown to be effective.”

More on HIV: Joe Rogan’s Idiotic New Theory: AIDS Is Caused by Poppers