Fighting HIV

By refining previous research, scientists are developing a new strategy that could be used to fight HIV. The technique would allow doctors to re-engineer a patient’s own T-cells, which are produced by the immune system to battle the virus. It has thus far been demonstrated successfully in both mice and human cell cultures.

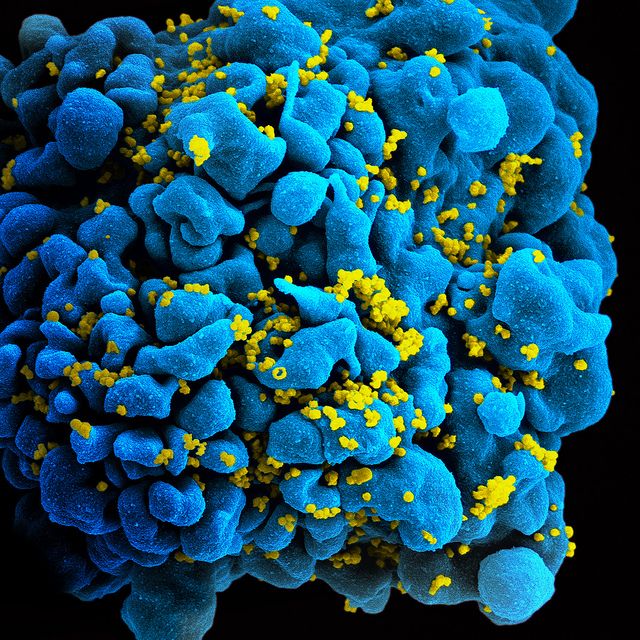

T-cells, a type of white blood cell, are central to the immune system’s response to HIV infection. While patients are treated with antiretroviral medications that manage the disease, the T-cells don’t have as much work to do. But if patients are not on antiretroviral medications, or the medications aren’t effective, the T-cells are absolutely central to fending off HIV.

That being said, HIV evades T-cell attacks using several strategies, so researchers have been attempting to re-engineer T-cells to fight HIV more effectively for quite some time. One such attempt made it to clinical testing, but was not successful enough to be used in patient treatments.

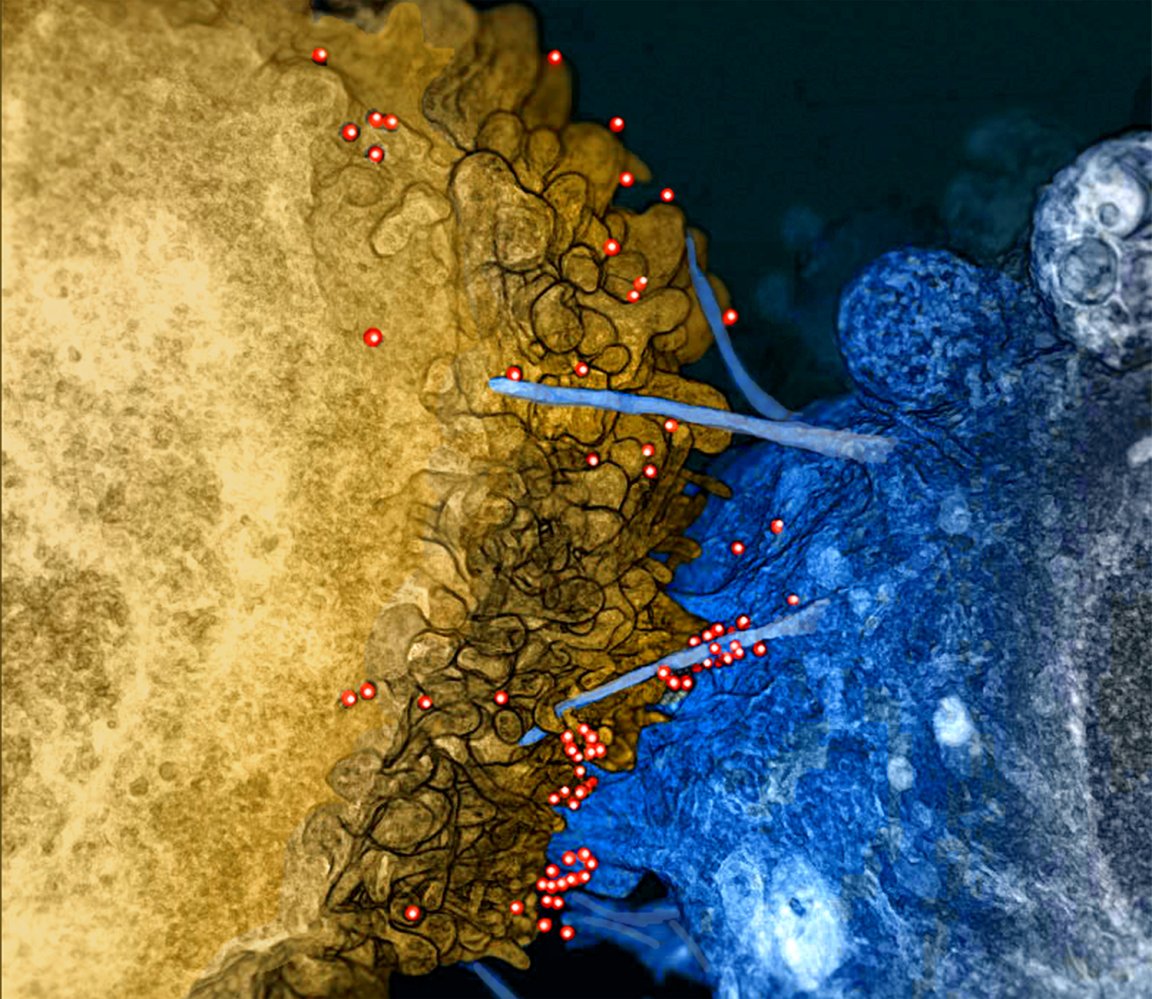

Now, building upon that attempt that made it to clinical trials, researchers have created a new technique that boosts T-cells with a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) — a synthetic protein that enables the cells to target the HIV virus more effectively. In the context of treatment, doctors would extract T-cells from a patient’s blood and re-engineer them to express HIV-specific CARs in the lab. The cells would then be infused back into the patient. This type of CAR-based technique has also been used to successfully enhance T-cell attacks of certain types of cancer cells.

Enhancing Bit By Bit

The team enhanced the same CAR protein that underwent clinical testing using recent advances in CAR technology. Several different segments comprise the protein itself, so the team optimized each one systematically instead of focusing on the protein’s performance as a whole. In testing the ability of modified T-cells to prevent the spread of the virus between human cells in the lab, they found that T-cells expressing the new CAR were more than 50 times more effective than those expressing the original CAR protein.

The team also tested their enhanced CAR protein in HIV-infected mice. Mouse T-cells that had been re-engineered with the new CAR protein were able to guard other T cells against HIV attack. And although T-cells don’t play as central a role in patients receiving antiretroviral treatment, in mice taking antiretrovirals, the new CAR protein re-engineered T-cells were able to delay the HIV virus from rebounding even after drug treatment ended.

The next stop for the new version of CAR and these findings will hopefully be clinical testing of the enhanced T-cell re-engineering. If clinical trials are successful, it may become possible to control HIV without antiretroviral treatment. “Our data shows for the first time that engineered T cells can significantly control viral rebound in the absence of ART in vivo,” the authors stated in a press release. “Our next step is to take this concept forward into the clinic.”