Drug of the Past

Although it seems like a problem of the past, women are still dying in childbirth across all areas of the world. In fact, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), roughly 830 women die in childbirth each day. Many of the causes are preventable, and of these, blood loss is the biggest contributor, killing roughly 100,000 women after they give birth every year.

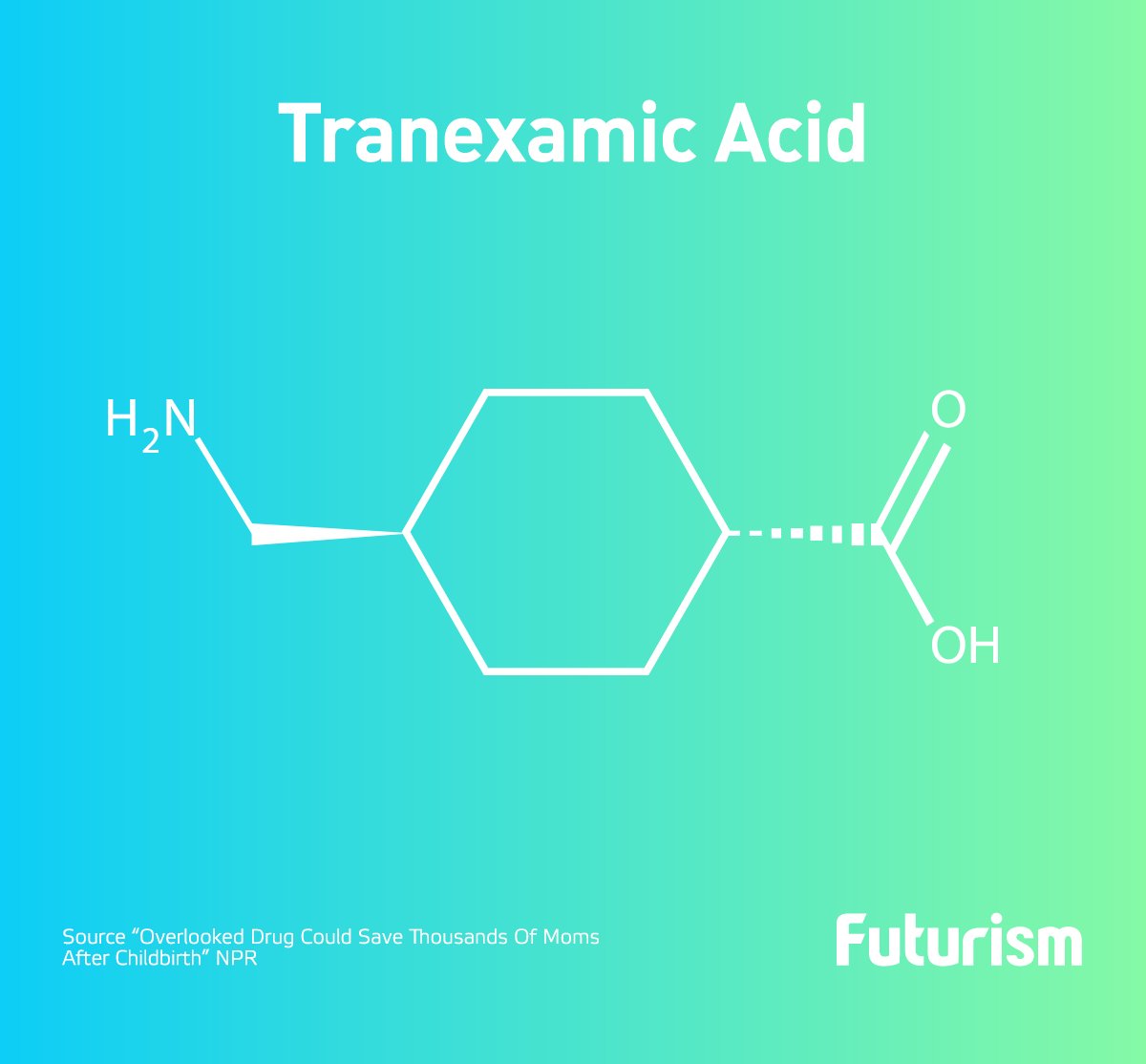

The thing is, it needn’t be the case. In the 1960s, a Japanese doctor named Utako Okamoto developed a powerful drug, tranexamic acid, that prevents hemorrhage after childbirth. “It was Okamoto’s dream to save women,” Haleema Shakur told NPR. “But she couldn’t convince doctors to test the drug on postpartum hemorrhaging.”

That is, until now.

Shakur headed up clinical trials at the London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene for the tranexamic acid that Okamoto developed. The trials involved 20,000 women from about 200 hospitals across 21 countries. After each woman was diagnosed with postpartum hemorrhaging (heavy bleeding after childbirth), she was given either the drug or a placebo.

Roughly 1.2 percent of the women who received tranexamic acid within three hours of hemorrhaging died, according to the study, which was published in the journal The Lancet. Meanwhile, 1.7 percent died after receiving just a placebo.

A Lifesaver

[infographic postid=”67918″][/infographic]

“I think the study is exciting,” said Felicia Lester, an OB-GYN at the University of California, San Francisco, who does work in Uganda and Kenya. “I’m usually cautious in saying that. But it looks like tranexamic acid has the potential to save lives.”

According to the WHO, 99 percent of all maternal deaths take place in developing countries, and women in rural areas or poorer communities are more likely to fall victim than those in cities or wealthier areas. Because tranexamic isn’t costly to produce —only about $3 in the U.K. and just a quarter of that in places like Pakistan—its potential could easily extend to these remote areas and poorer communities.

“If you can save a life for approximately $3, then I believe that’s worth doing,” said Shakur. Now, we just need to make sure the drug actually gets to the women who need it the most.