Researchers have discovered an “unexpected” accumulation of the radioactive isotope beryllium-10, deep underneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

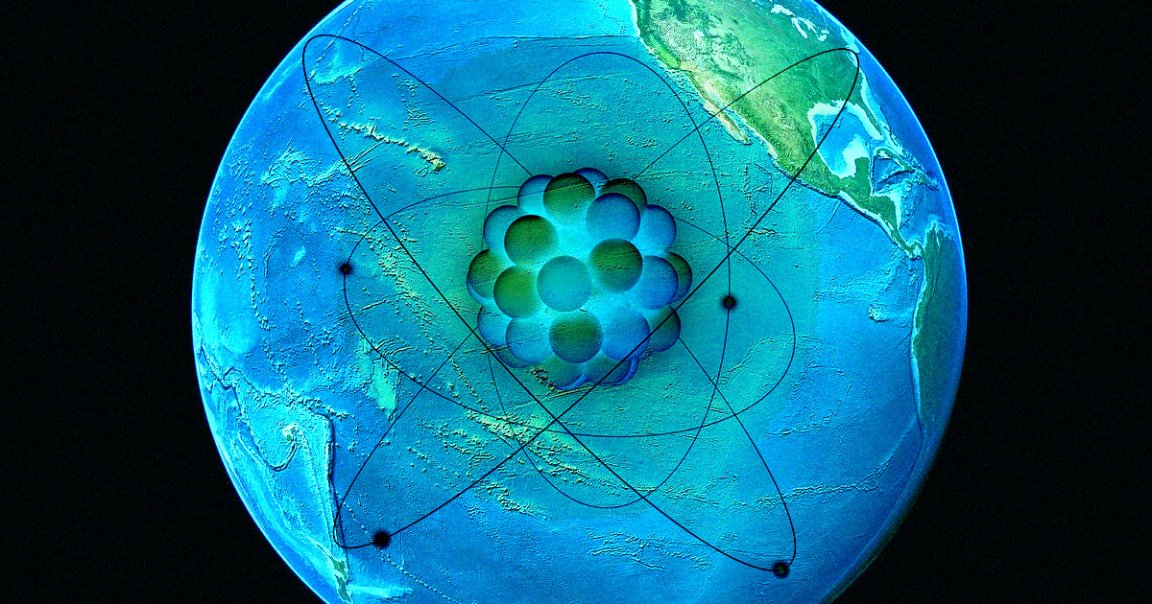

As detailed in a paper published in the journal Nature Communications, the international team of scientists believes that the “anomaly” dates back to shifts in ocean currents or cosmic rays interacting with the Earth’s atmosphere approximately ten million years ago. Beryllium-10 is known to be continuously produced by oxygen and nitrogen atoms in the Earth’s upper atmosphere interacting with high-energy protons, which race through the universe at nearly the speed of light.

The team hopes their discovery could serve as an “independent time marker for marine archives,” allowing scientists to get a better sense of how the planet’s crust has evolved over millions of years, and better calibrate geological data sets.

Radioactive isotopes are typically used by researchers to date archaeological and geological samples. Radiocarbon dating is one such application, but it comes with some notable limitations.

While samples of things like wood or bones can be accurately dated, the “radiocarbon method is limited to dating samples no more than 50,000 years old,” explained coauthor and Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf physicist Dominik Koll in a statement. “To date older samples, we need to use other isotopes, such as cosmogenic beryllium-10.”

The isotope’s half-life is a whopping 1.4 million years, and breaks down into boron, allowing scientists to look much further back in time, over ten million years.

As detailed in their paper, Koll and his colleagues examined geological samples taken from the Pacific Ocean’s bed miles below the surface. They examined the proportion of boron isotopes using accelerator mass spectrometry.

The results surprised them.

“At around 10 million years, we found almost twice as much [boron-10 isotope] as we had anticipated,” Koll recalled. “We had stumbled upon a previously undiscovered anomaly.”

The team can only offer informed guesses as to what caused the anomaly around the time gibbons and orangutans genetically split, leading to the earliest humans.

The researchers suggest there could’ve been a “grand reorganization” of ocean currents, depositing more than expected amounts of beryllium-10 in the Pacific.

Perhaps most intriguingly, the anomaly may have been the result of a powerful celestial event, like a “near-Earth supernova” that could have temporarily intensified cosmic radiation ten million years ago, according to the scientists. A collision with an interstellar could’ve also made the Earth’s atmosphere more vulnerable to a bombardment of cosmic rays.

“Only new measurements can indicate whether the beryllium anomaly was caused by changes in ocean currents or has astrophysical reasons,” Koll explained in the statement. “That is why we plan to analyze more samples in the future and hope that other research groups will do the same.”

For instance, if similar discoveries were to be made in other oceans, it would suggest that the anomaly was a global phenomenon — supporting the latter astrophysical hypothesis.

More on cosmic rays: Scientist Warns That NASA’s Voyager Probes Are “Dodging Bullets Out There”