There’s a negative side to the news that a second team of scientists successfully modified human embryos, making them HIV-resistant. The team was able to modify some but not all embryos in the study. And it seems that HIV can actually defeat our efforts to cripple it with CRISPR gene-editing technology.

Ultimately, it seems that CRISPR itself may introduce mutations that help HIV resist attack; however, the team behind the work thinks that these problems may be surmountable.

Resisting Attack

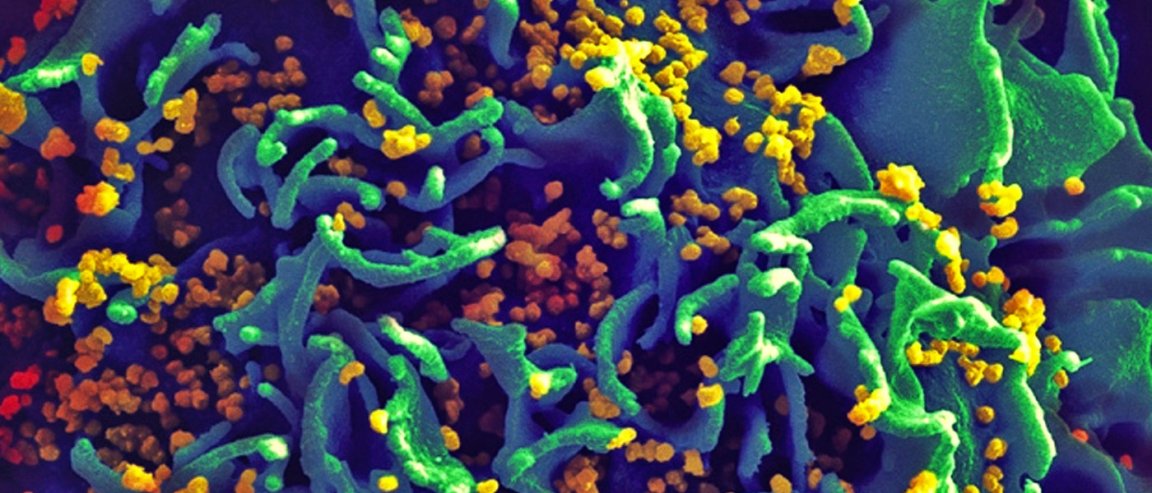

When HIV infects a T cell, its genome is inserted into the cell’s DNA, and it hijacks its DNA-replicating machinery to churn out more copies of the virus. But a T cell equipped with a DNA-shearing enzyme called Cas9 can find, cut, and cripple the invader’s genome.

That method did seem to work, at least for a short period of time, when a team led by virologist Chen Liang, at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, infected T cells that had been given the tools to stop HIV. But two weeks later, Liang’s group saw that the T cells were pumping out copies of virus particles that had escaped the CRISPR attack.

Liang’s team believes that the mutations occurred when Cas9 cut the viral DNA. When DNA is cut, its host cell tries to repair the break; in doing so, it sometimes introduces or deletes DNA letters. These ‘indels’ usually inactivate the gene that was cut — which is how CRISPR works. But sometimes this doesn’t happen.

Occasionally, Liang thinks, some of the indels made by the T cell’s machinery leave the genome of the invading HIV able to replicate and infect other cells. And worse, the change in sequence means the virus can’t be recognized and targeted by T cells with the same machinery. This means it becomes resistant to any future attack.

Altering Human Genes

Liang thinks that the challenges seen in this study can be overcome. He suggests inactivating several essential HIV genes at once, or using CRISPR in combination with HIV-attacking drugs. Gene editing therapies that make T cells resistant to HIV invasion (by altering human, not viral, genes) would also be harder for the virus to combat.

A clinical trial is under way to test this approach using another gene-editing tool, zinc-finger nucleases.