Fake Harvard Students

According to his bio on Harvard.edu, Mikao John was an erudite scholar: a medical student at the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology who’d studied statistics and biochemistry at Yale and published research in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine.

John was also a prolific author of blog posts on Harvard’s site, each of which appeared under the words “Harvard University” and the school’s crimson “veritas” seal, and above a message claiming copyright by the “President and Fellows of Harvard College.” But despite that veneer of academic authenticity, his posts didn’t sound much like medical research.

Instead, John’s recent works carried titles like “KeefX.co: The Cannabis Fintech Company that Provides $1M in Funding a Month,” which took the form of an extremely flattering article about a startup that provides financial services to weed businesses, and “Idahome Solar Makes Switching to Solar Power in Idaho a No-Brainer,” which praised the “client-first mentality” and “incredible financing program” of a seemingly random solar panel company in Idaho.

As it turns out, there is no Harvard student by the name of Mikao John. Instead, a scammer invented that persona — and, alarmingly, managed to obtain the credentials to insert him into Harvard’s web system — in order to sell SEO-friendly backlinks, and the prestige of being hyped up by someone at one of the world’s most distinguished universities, to marketing firms with publicity-hungry clients.

The practice of scammers cooking up fake Harvard students to shill brands on the university’s site appears to be widespread. In response to questions from Futurism, Harvard removed the Mikao John profile as well as about two dozen similar accounts being used for the same purpose.

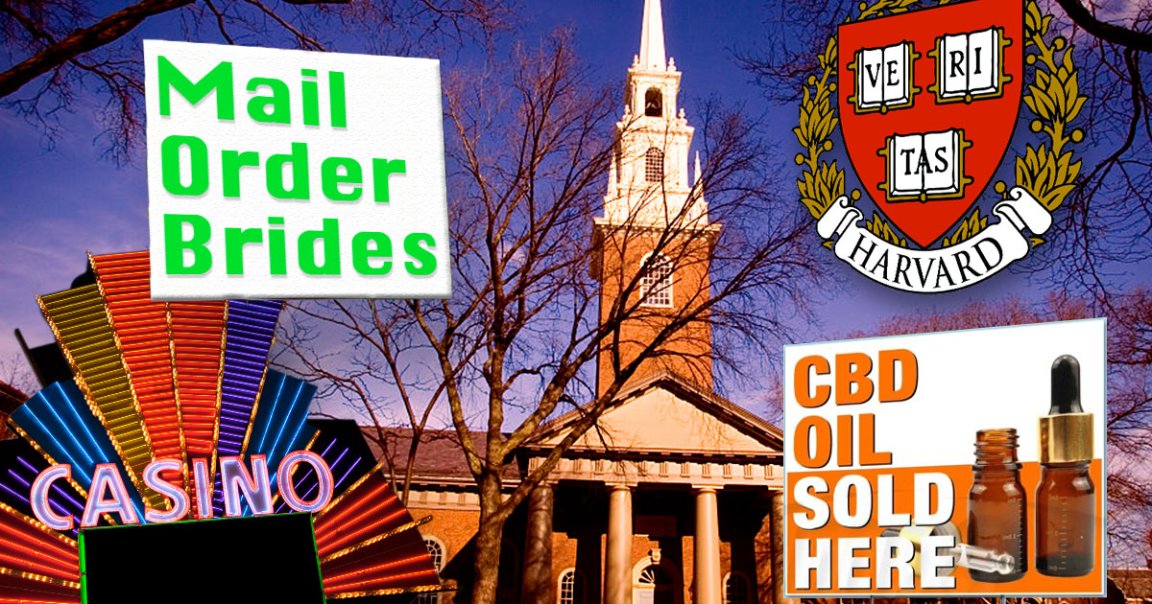

According to emails advertising the scheme obtained by Futurism, a Harvard blog post from a fake student like John can be bought for as little as $300 via PayPal. Some are anodyne, promoting things like hair loss treatments and car insurance. Others are disturbing, like a post on an account that appeared to be halfheartedly impersonating Harvard itself, with the username “Harvard2,” that made overtly racist and sexist generalizations about women and advertised a site purporting to sell “mail order brides.”

In short, swathes of Harvard.edu have become a spammer free-for-all where fake students and other accounts hawk an endless parade of dubious stuff: online casinos, synthetic urine, real estate in Florida, CBD, wireless speakers, coupons, tourism in Krakow, garage door openers, UV sanitizers, DUI attorneys, nutritional supplements, fitness supplements, orthodontists, pet products, more pet products, cannabis delivery, bathroom fixtures, a random moving company in New York, online therapy, concealed carry holsters, kitchen sinks, more kitchen sinks, more kitchen sinks, more kitchen sinks, bitcoin mining, vacuum cleaners, foot massagers, ob/gyn clinics, lawn decorations, bouncy castles, ottoman beds, automotive mechanics, seasonal depression lamps, exercise equipment, more exercise equipment, a realtor in Winnipeg, weighted blankets, home security alarms, roller skates, narration services, keto-friendly snacks, a site for hiring motivational speakers, flatscreen TVs, creatine supplements, fertility doctors, commercial power washing services, and many more incongruous yet trashy brands and services.

Basically, it appears that anyone with $300 to spare can — or could, depending on whether Harvard successfully shuts down the practice — advertise nearly anything they wanted on Harvard.edu, in posts that borrow the university’s domain and prestige while making no mention of the fact that it in reality they constitute paid advertising. According to Google’s indexing, certain parts of Harvard’s site had become almost entirely taken over by low-quality spam before the university started removing the posts in response to our questions.

A Harvard spokesperson said that the university is working to crack down on the fake students and other scammers that have gained access to its site. They also said that the scammers were creating the fake accounts by signing up for online classes and then using the email address that process provided to infiltrate the university’s various blogging platforms.

“Harvard provides several web publishing options to members of our community for academic and business use,” the spokesperson told Futurism. “We are aware of a number of cases where individuals have registered for an online Harvard course to obtain the credentials allowing them to create a website, then used the website to post SEO spam.”

“These cases of unauthorized use are due to misuse of a process, not due to a technical vulnerability,” the Harvard spokesperson continued. “We are committed to ensuring Harvard’s web publishing resources remain accessible and easy to use for members of our community, while strengthening our processes to prevent fraudulent use.”

People involved in placing the blog posts on Harvard’s site expressed little remorse.

One of the companies featured in a blog post by Mikao John, for instance, told Futurism that the mention had been secured through a marketing firm called T1 Advertising, which conceded in response to questions that it sometimes pays “media consultants” to plant blog posts on Harvard’s site.

Thomas Herd, the founder of T1 Advertising, told Futurism that he saw no ethical problem with the arrangement.

“As to the name of the author, the part of the site it’s on, the access they have to Harvard, etc, that’s all completely out of our control (as T1 has no access directly to Harvard),” he said in an email.

“If there was something wrong in how they’re publishing blog posts (or if there is issue with the name under which the articles are appearing),” he continued, “then this is the first time I’m hearing about it and responsibility would ultimately lie with the access Harvard has given [the media consultants] or with how they’re representing their services to us and numerous other agencies these consultants reach out to offering blog post services.”

Herd appears to have even leveraged the service to build his own personal brand, in a Harvard blog post titled “Thomas Herd Drives Academic Revolution In Digital Marketing.” In the post, which was written to sound as though Herd is being interviewed by an official arm of Harvard University, and which makes no mention of the fact that it was a paid advertisement, Herd brags that his marketing techniques are the “holy grail every brand or company owner seeks.”

When contacted by Futurism, an operative who Herd said had secured posts on behalf of T1 complained that Harvard had been removing her clients’ posts lately, seemingly in response to Futurism’s investigation.

But, she said, she had a contact at Harvard who she paid for access to the site — a charge that Harvard denied, citing an internal investigation — and expected access to be restored soon.

At first, Harvard’s response to the fake students was surprisingly sluggish. After initially being notified of the Mikao John account, for instance, a spokesperson said that the posts would be removed, but then they stayed up for another two weeks until Futurism sent a followup message.

Overall, it felt as though if a reporter hadn’t been sending numerous emails, the fake students probably would have been allowed to continue posting indefinitely.

In a broad sense, Mikao John and the other fake students illustrate the perils of user-generated content, a term for when institutions or publications allow community members to post material with little scrutiny.

In theory, it’s a nice idea. But when media brands including Forbes and Entrepreneur have leveraged the concept to create “contributor networks,” in which unpaid and thinly credentialed writers are allowed to post authoritative-sounding articles about the world of business, the result has often been that those same poorly-vetted writers start soliciting payoffs from marketing firms in exchange for publishing flattering stories about their clients.

Harvard’s fake student problem seems to be a related issue. By providing a platform for students and other community members to post whatever they want — and by opening the system to anyone who registers for an online class — the university is inadvertently incentivizing a black market in which scammers sell access to its site for SEO and marketing purposes.

It’s also worth noting that the ability to post anything you want to Harvard’s site, under the name and credentials of a seemingly-legitimate researcher like Mikao John, could be used to do things far more nefarious than selling CBD and hair loss treatments. It’s not hard to imagine an enterprising scammer shorting a specific biotech company’s stock, for instance, and then paying to place a skillfully-written Harvard blog post attacking its technology, buying reach for the damaging story on social media, and then cashing in on the ensuing controversy.

The fake accounts also come in the context of a broader conversation about misinformation online. If an anti-vaccine activist or a political operative had wanted to pay to dispute the effectiveness of the COVID vaccine or undermine confidence in election results in the guise of a Harvard student or researcher, it would have been trivially easy for them to do so.

The reality, though, is that nobody involved scheme seemed to grasp how powerful their access actually was — or even to think very hard about the implications at all.

For instance, we asked one scammer who was selling access to the fake students whether he thought Harvard would mind what he was doing.

“I don’t know,” he replied.

More on Harvard: Harvard Scientist Suggests That Our Universe Was Created in a Laboratory