Consent should be simple: either it exists clearly on both sides or it doesn’t. The #MeToo movement, started by Tarana Burke, has illustrated the stark reality of sexual harassment and assault — one that’s complicated. And many would argue needlessly so. While a great number of people have been aware of the reality (and have been for a long time) those coming forward now with their stories have sparked an honest, global conversation about consent.

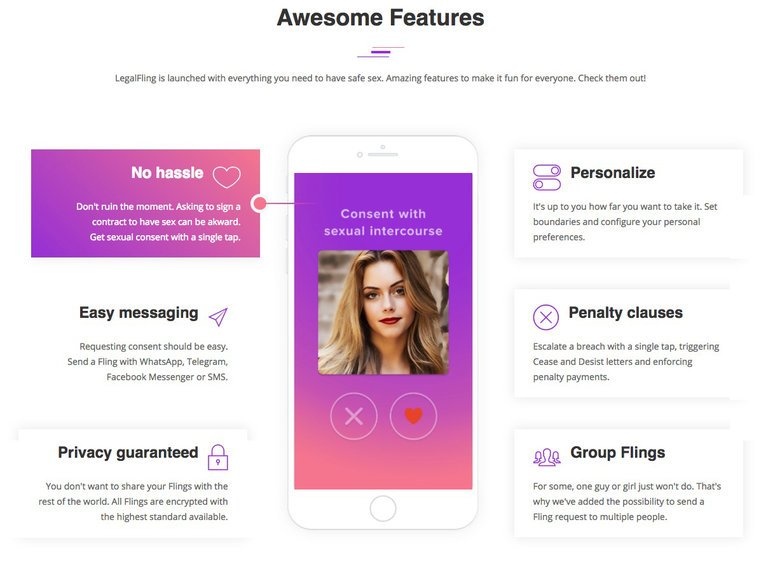

From within this conversation, some are looking to tech in search of solutions. On Monday, a Dutch company introduced the beta version of an app called LegalFling, which allows users to give consent in a “live contract,” and the interaction is sent through the Waves network. The contract can be continuously updated and changed, for example, if a person consents initially but then changes their mind later on. Since the app operates on the blockchain, the records are a permanent part of the public ledger.

A technology-driven solution to the problem of consent might seem natural in the online era in which we live, but it could cause more issues than it solves. Issues that, quite frankly, shouldn’t exist at all.

As Andrew D. Cherkasky, a former special victims prosecutor who now works as a criminal defense attorney for sexual assault cases, told the New York Times, information from the app could hold up in court. However, app data on whether or not both parties consented — and whether or not the changed consent status was reflected in the app— might not give a court the full story. Missing or omitted information notoriously complicates even cases that aren’t tech-based.

For example, if at the beginning of an encounter both people consent in the app, but one party decides halfway through that they want to stop, it seems like it could be all too easy for the other party to prevent them from getting back into the app to log the change in consent. Or, if a person simply decided to leave, they might forget to change their consent status in the app.

Beyond its potential to complicate court cases, for many, the real issue is that such an app shouldn’t be necessary at all. But as we’ve seen with #TimesUp and #MeToo, our society is completely ingrained with subtle, but persisting, standards and behaviors rooted in a long and troubled history. One where the very definition of consent has been not only challenged but manipulated — and ultimately violated.

While it can be taken as a sign of positive change that there’s interest in preventing assault and protecting consent, the focus needs to be on the problem itself — why it exists and how we can address it. For that, an app is not the solution.