Researchers claim that China’s Zhurong rover, which has spent months exploring the Martian surface, may have found evidence — though not quite proof — of liquid water at low latitudes where temperatures are relatively warm and more suitable for life.

It’s a provocative claim, as until now scientists believed only solid or gaseous states of water can exist on the Red Planet, after drastic periods of climate change caused what scientists suspect to have been vast reserves of liquid water to dry up in the planet’s ancient history.

The finding also highlights that there’s still a chance of discovering evidence of ancient life — and perhaps even habitable areas on the planet’s current-day surface.

While we’ve found plenty of evidence for frozen water, Mars’ incredibly thin atmosphere makes it near impossible for liquid water to exist on the planet.

Salty droplets of water that landed on the arm of NASA’s Phoenix Lander, which touched down on Mars in 2008, led scientists to believe that liquid water was able to exist at high latitudes on Mars, a conclusion that proved controversial at the time.

As detailed in a new paper published in the journal Science Advances, a team led by Xiaoguang Qin, a geophysics professor at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, found that liquid water may also be able to exist at lower altitudes.

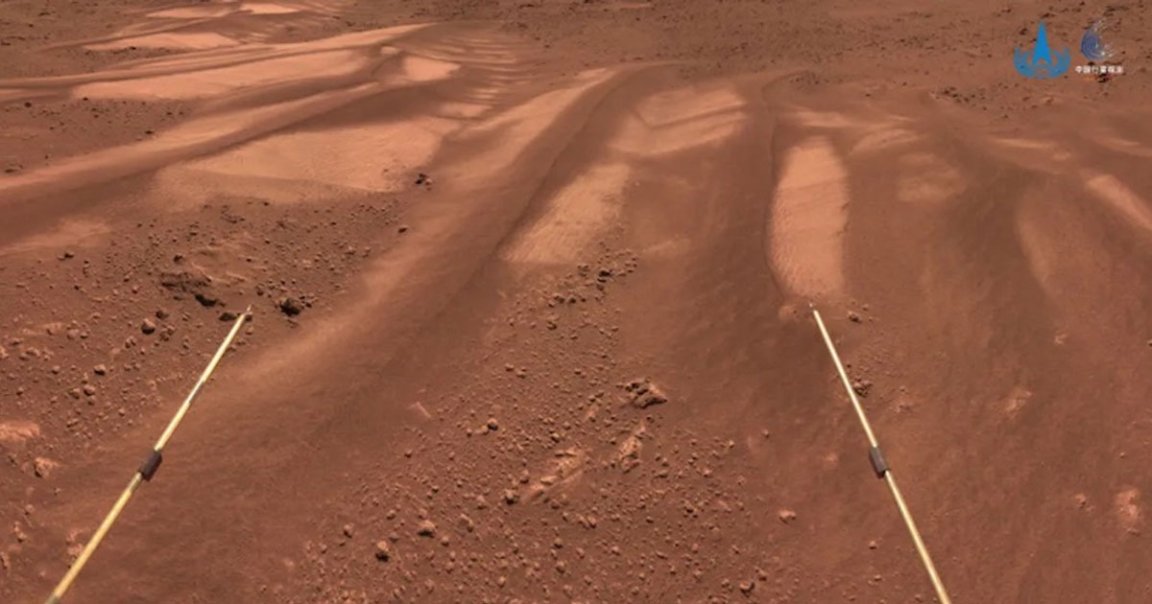

Data from three of Zhurong’s scientific instruments, which were tasked with analyzing surface features and composition of dunes, suggest their surface layer is rich with hydrated sulfates and silica, as well as oxide minerals.

This salt allows for ice or snow to melt at lower temperatures, the researchers propose.

“According to the measured meteorological data by Zhurong and other Mars rovers, we inferred that these dune surface characteristics were related to the involvement of liquid saline water formed by the subsequent melting of frost/snow falling on the salt-containing dune surfaces when cooling occurs,” said Qin in a statement.

But while this underlines standing theories surrounding the snow-or-ice-to-water vapor cycle in the atmosphere at lower altitudes, “no water ice was detected by any instrument on the Zhurong rover,” as Qin told Space.com.

The researchers suggest humid environments throughout the planet’s history allowed for frost or snow to repeatedly melt and refreeze as it made its way from the planet’s polar ice sheet to its equator, causing crusts and cracks to form on the surface, and leaving behind liquid salty water.

The dunes, which are anywhere between 400,000 and 1.4 million years old, were once rich in these hydrated sulfates and minerals, according to the research.

“This is important for understanding the evolutionary history of the Martian climate, looking for a habitable environment, and providing key clues for the future search for life,” Qin added.

The team is now suggesting that “priority should be given to salt-tolerant microbes in future missions searching for extant life on Mars” — a tantalizing clue in the search for Martian life.

More on water: Scientists May Have Finally Figured Out Where Earth’s Water Came From