FROM FLOWERS TO BATTERIES

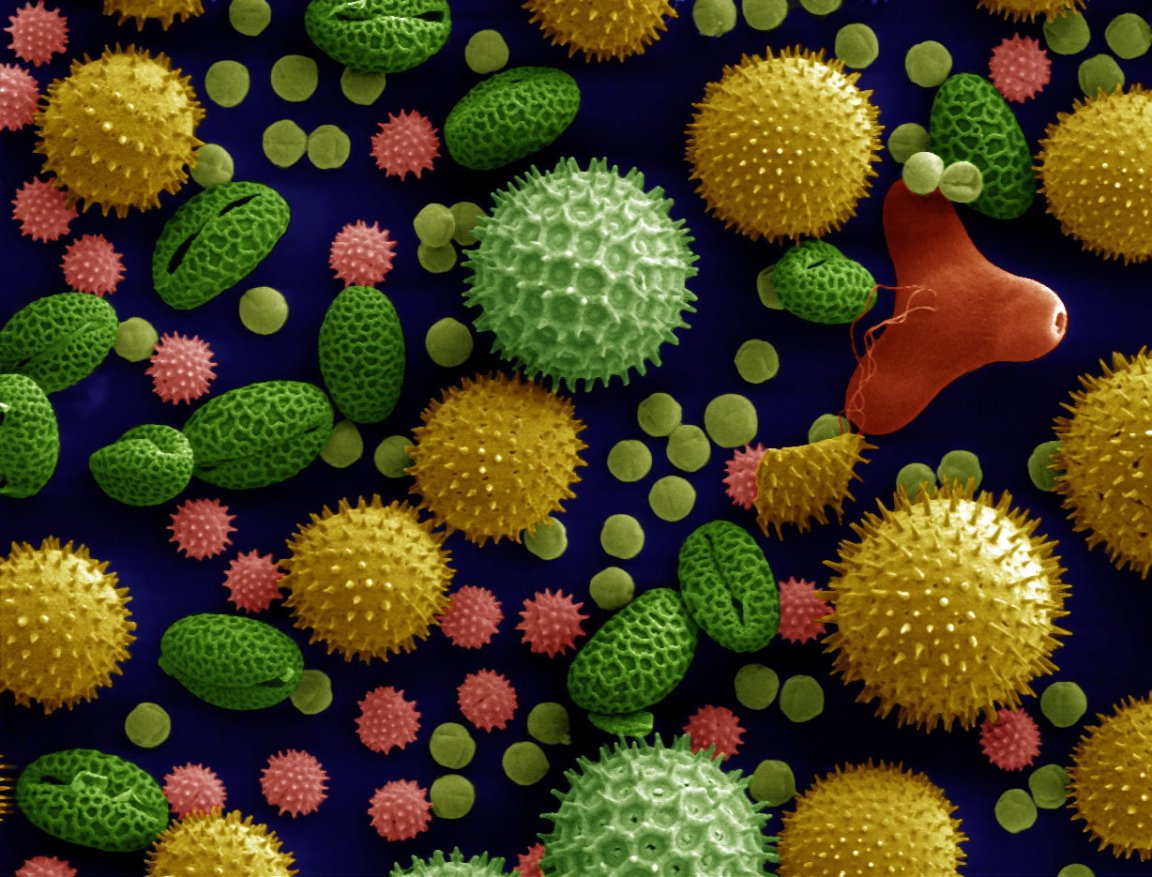

When it comes to materials you’d expect to be present in your battery, pollen is probably on the far end of the list. But a new discovery may soon change things.

While we mostly associate pollen with hay fever, scientists were recently researching something entirely different. Instead, they were looking at how they could use pollen as an alternative to graphite in lithium-ion batteries. Early results for this research suggests that nature-derived pollen structures could be used as an efficient and renewable alternative to graphite.

In addition, further data also seems to indicate that it is capable of delivering a far superior battery performance.

“I started looking into pollens when my mom told me she had developed pollen allergy symptoms about two years ago,” said researcher Jialiang Tang. “I was fascinated by the beauty and diversity of pollen microstructures. But the idea of using them as battery anodes did not really kick in until I started working on battery research and learned more about carbonisation of biomass.”

How Batteries Work

Batteries are composed of two electrodes, a positive end (the cathode) and a negative end (the anode). By connecting these two ends with a wire or any other conductor, electrons flow along the circuit formed and produces the current of electricity needed to run our devices.

Digital devices like smartphones and notebook computers use lithium-ion batteries, which have utilized graphite as its anode since its inception in 1991. Now, researchers are looking for new materials that could replace graphite as its limitations become more and more apparent.

“Our findings have demonstrated that renewable pollens could produce carbon architectures for anode applications in energy storage devices,” said one of the team, Vilas Pol.

SWEET PERFORMANCE

The researchers were interested in experimenting with two kinds of synthetic pollen that they obtained from natural sources: bee pollen and cattail pollen. “Both are abundantly available,” said Pol. “The bottom line here is we want to learn something from nature that could be useful in creating better batteries with renewable feedstock.”

Using natural samples of each variety of pollen, the researchers processed them in a chamber filled with argon gas at a high temperature by performing a procedure called pyrolysis. Bee pollen, which is a mixture of the differing pollen types obtained by bees, contains varying shapes in contrast to cattail pollen, which all have the same shape.

Ultimately, the end result of the pyrolysis results in pure carbon in the shape of the pollen particles. Further heating in the presence of oxygen opened up pores in the structures that increases their energy-storage capacity.

Tests conducted by the scientists showed that charging for 10 hours resulted in a full charge, and that more than half of a full charge could be achieved in just one hour. Comparisons between the two showed that Cattail pollen outperformed bee pollen with a high capacity of 590 milliamp hours per gram in testing at 50 degrees Celsius and 382 mAh/g at 25 degrees Celsius.

“The theoretical capacity of graphite is 372 milliamp hours per gram, and we achieved 200 milliamp hours after 1 hour of charging,” said Pol.

While the research may be preliminary, the scientists seek to study pollen in a full-cell battery with a commercial cathode. Further research is needed to see if their idea could actually be practical and commercially viable for consumer use, but it’s promising early work.