Trying on lipstick before you bought it once meant dealing with an apathetic store assistant and the dubious hygiene of putting your lips on the same surface as countless fellow shoppers.

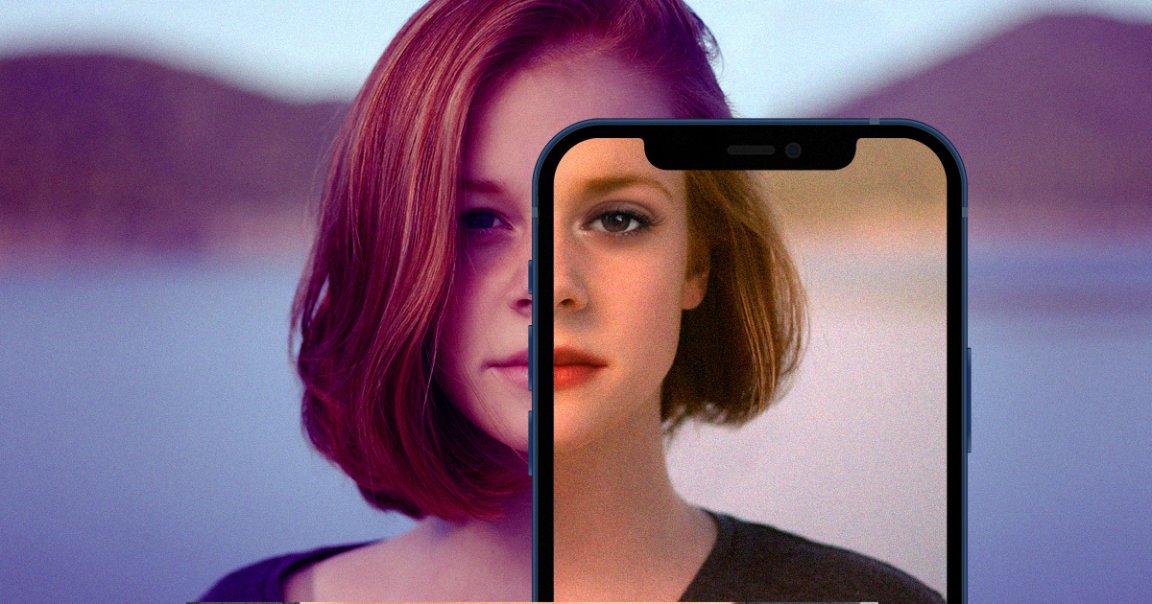

Now, amplified by the pandemic, a flurry of prominent cosmetics brands are trying to reproduce that experience in apps that superimpose digital representations of cosmetic products, from brows to eyeliner to contouring cream, onto your face as viewed through your phone’s front facing camera. And then, of course, they try to sell that augmented reality vision to you in real life.

Take Pam McKim, an Orange County resident who recently downloaded My Dior, an app by storied fashion brand Christian Dior, for her iPhone 12. McKim tried on several shades of lipstick by digitally projecting them onto her face, ultimately ordering two hues of the company’s Addict Lip Glow Oil — 001 Pink and 006 Berry, to be precise — directly from the app.

“It was an interesting concept, so I tried it,” she told Futurism. “My lips were fire.”

The trend is already making deep inroads into the beauty industry, which is estimated to be worth more than a half-trillion dollars. Prominent brands including Rihanna’s Fenty Beauty, Glossier, Gucci, NYX, Maybelline and Makeup Revolution are all experimenting with variations on the tech, some in increasingly serious ways. In 2018, cosmetics behemoth L’Oréal bought an entire AR development studio, ModiFace, to help build out its offerings in the space.

“It will be entirely normalized before you buy any cosmetic product,” said Tom Cheesewright, a business consultant in the UK. “Then you can actually create a really sick, digital experience, at very low cost to the brand.”

Behind this phenomenon is springing up a cottage industry of AR developers who specialize in the new convergence of cosmetics and filters.

Software developer Poplar Studio, for instance, has done work for brands including L’Oréal, NYX and Maybelline to create what those in the AR industry often call “experiences.”

“People don’t necessarily want to travel to a store to just try stuff before you buy it,” Poplar CEO David Ripert told Futurism.

The beauty industry, he says, demands a level of fidelity that users don’t necessarily expect from an Instagram filter that adds bunny ears or a flower crown.

“The way it works for most technology out there is that it’s going to apply what we call a mask,” he said, which Poplar accomplishes by training the system with thousands of photos and 3D models of actual people’s face. “On that mask we’ve said this is the lip color and this is the blush and this is what we’re going to modify, and it’s going to try to apply that mask on top of your face.”

The difficulty, he said, is that “all our faces are different, and your lip form is different from mine and everybody else. It’s not going to look as realistic as possible unless it completely matches your own form, and that requires a lot of development.”

And just as challenging as the variety of human faces, he said, is the unpredictability of the environments they can appear in.

“There might be things like, for example, reflections, like I’m looking at you on the camera right now as you move your face,” Ripert said. “So because you might have a blue light or maybe your wall is hard, color is going to reflect that on your skin.”

The specifics of Poplar’s work can vary significantly. For a recent collaboration with Maybelline, for instance, Ripert’s team built an Instagram filter that digitally erases the user’s brows and then lets them swap in products like the company’s eyebrow pomade crayons. The goal, he said, wasn’t just to show the final result but also to give a sense of how intuitive the products were to apply.

And sometimes the goal is to create an outright narrative. For a Halloween-themed Instagram filter for NYX, Poplar created a virtual “haunted house” that let users meet horror film-style characters like Prima Ballerina and Broken Beauty, and virtually try on each one’s makeup aesthetic.

For cosmetics brands, of course, there are two looming questions about this nascent tech: whether it connects with and holds the attention of users, and whether it lead them to actually make purchases.

“Is this one of those shiny new things?” asked retail consultant Catherine Erdly. “Is this a beautifying filter, or is it a demonstration of what the product can do?”

There’s often a line between a gimmick and a groundbreaking technology. QR codes, for instance, languished for a decade — before finally picking up significant steam during the pandemic as a touch-free way to pull up everything from restaurant menus to medical info. Whether AR will ever pick up that level of ubiquity, in the beauty industry or elsewhere, remains to be seen.

There’s also the question of how effective the tech actually is at depicting the nuances of a real product on your face. The filters can be immediately impressive on a technical level, but often fail to capture the subtleties of texture and lighting that makeup connoisseurs are looking for in a retail environment. The underlying technology is bound to keep improving, but currently it still lacks the sophistication needed to eclipse actually trying a product on.

And as with other filters on social media, the tech also raises questions about the relationship between enhancement and fabrication. Faces exist in the real world, but they also exist as data, as with the masks that Poplar works with, and the delineation has never been less clear.

“It’s giving off this false impression that actually this filter is magically making you all around more beautified,” Erdly said, echoing an observation by McKim, who opined that the app “clearly facetuned me before putting the colors on.”

In other words, the rise of AR in the beauty industry falls onto a preexisting spectrum of digital representations of our selves, from Snapchat to Instagram and TikTok to Zoom, all of which offer some form of beautifying filters.

Eventually, the question might become which matters more, and in which contexts: the analog version of yourself, or the digitized one? It’s easy to imagine a world, perhaps in five or ten years, in which doing your makeup won’t mean spending hours in front of a mirror — instead, maybe it will be more like a “customize your character” selection screen in a video game that shows others how to perceive you on their own AR hardware.

One thing, at least, is clear: the makeup companies are trying to fill that uncanny valley as soon as possible — with your dollars, time, and attention.