The night sky is cluttered with debris. A constant hail of space junk falling out of orbit, mixed with ever-growing trains of SpaceX satellites, means that observations of the cosmos are now forever cluttered. Interference from satellites is so prevalent that it’s now threatening to block out the protected radio bands used to detect emissions from celestial objects.

But what if we could turn back the clock to a time before Elon Musk was even a twinkle in his dear old dad’s eye? That’s exactly what researchers at the Vanishing and Appearing Sources during a Century of Observations project (VASCO) are doing: sifting through digitized records of the night sky to search for anything unusual in the heavens.

Specifically, VASCO’s task is to sift through archives of astronomical photos dating back decades, in order to “identify interesting astrophysical targets for follow-up analysis with extreme, exotic, or bizarre patterns of variability.”

The results can be intriguing. One of VASCO’s latest surveys, published in the journal Scientific Reports, found several mysterious transient objects in the night sky dated from between 1949 and when the first satellite, the USSR’s Sputnik, made it to orbit in 1957 — when there shouldn’t have been a single object launched by humans in orbit, in other words.

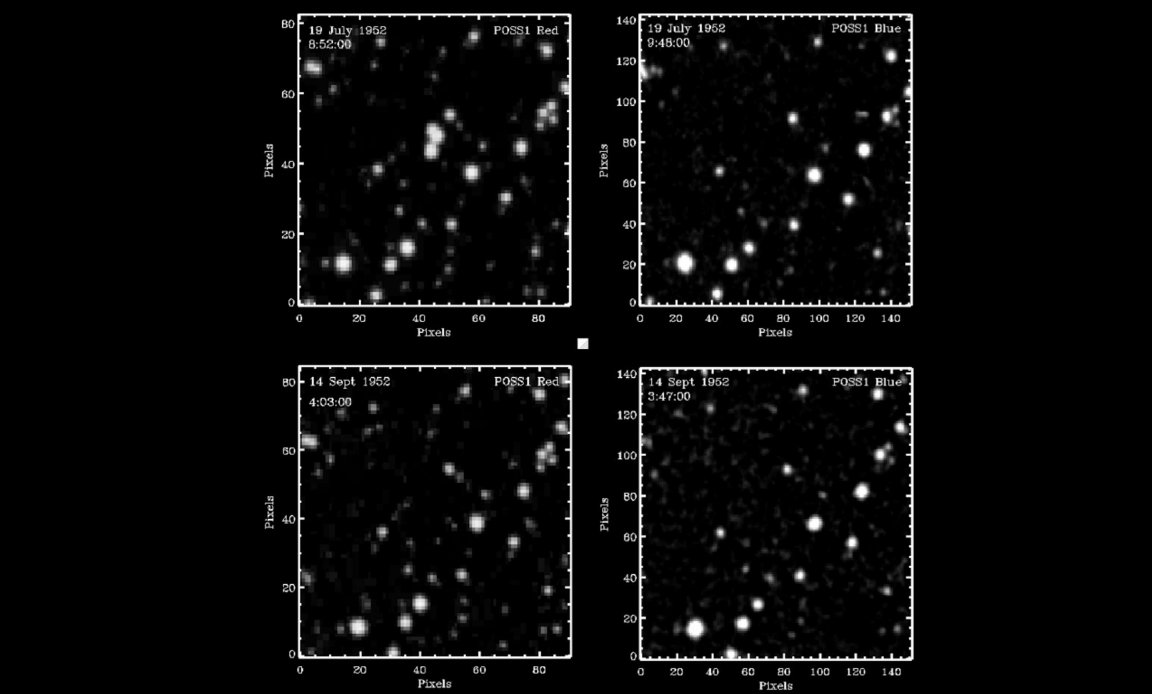

The transient “star-like objects of unknown origin” were first captured by the Palomar Observatory in San Diego. To qualify as “transient,” the phenomena have to have lasted less than 50 minutes — the time it took for Palomar to take one image — and not be explicable by conventional means, meaning they weren’t asteroids burning up or issues with the equipment.

Provocatively, the VASCO team found a correlation between the unexplainable lights and nuclear weapons testing, which was nearing a fever pitch during that period of time following WWII. In fact, the researchers found these transient objects were 45 percent more likely to show up within one day of an atomic test.

Even more strangely, the astronomers also noted a “small but statistically significant” link between nuclear weapons testing and reports of unidentified anomalous phenomena (UAPs). As for the Palomar lights, the paper found that the likelihood for transient activity rose by 8.5 percent for every reported UAP sighting.

In their paper, the VASCO team writes that their findings “provide additional empirical support for the validity of the UAP phenomenon and its potential connection to nuclear weapons activity, contributing data beyond eyewitness reports.”

The research is obvious catnip to anyone who suspects that humankind is being observed by intelligent visitors, particularly if those aliens were to have an interest in the development of nuclear weaponry.

But as Scientific American reports, there are other reasonable explanations for the lights identified in the research that are probably more likely. They could be radiation in the upper atmosphere caused by atomic weapons testing, for instance, or sightings of high-altitude balloons that were used to monitor nuclear detonations during the era. Or they might just be cosmological phenomena that are still observed today, like gamma-ray bursts, that were caught on equipment from the era.

One thing’s for certain: the research is controversial — SciAm notes that arXiv.org, a pre-print repository that will generally host a very broad range of studies as they’re scrutinized by the scientific community, declined to accept the paper that was ultimately accepted by Scientific Reports.

More on space: White House Orders NASA to Destroy Important Satellite