Rise of the Machines

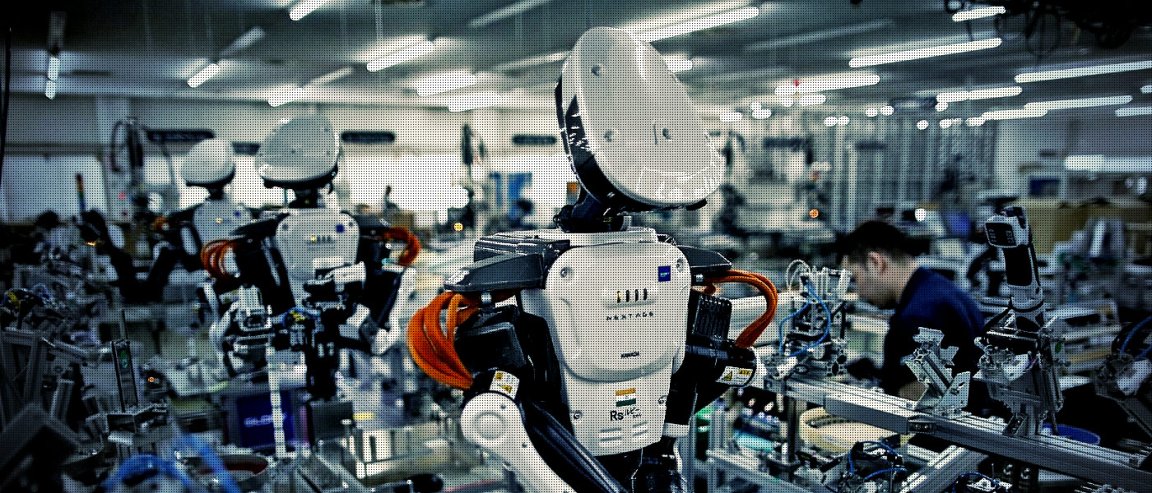

Not only can robots physically do more than humans, but soon, they could outperform us mentally as well. In fact, tasks once thought of as being quintessentially human, such as driving a car or deciphering handwriting, are already being done by machines.

So, what does this mean for humanity?

Well, it means less work, but that’s not necessarily a good thing. In a robust report entitled Technology at Work v2.0: The Future Is Not What It Used To Be, researchers at Citibank and the University of Oxford explore the implications of this rapidly changing technological landscape. Specifically, Dr. Carl Benedikt Frey, Associate Professor Michael Osborne, and Dr. Craig Holmes investigate the changing nature of innovation and work, and what these changes mean for the future of employment.

The Reality of Job Automation

To begin, the authors consider a job to be “exposed to automation” or “automatable” if the tasks that it entails allows the work to be performed by a computer, even if a job is not actually automated. A broad range of non-routine tasks are now automatable, thanks to connected devices, advances in user interfaces, and cheaper and better sensors.

In the original study, the team found that a staggering 47% of US jobs are at risk. The newest report looks at other countries, and it finds that things are even worse abroad.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data shows that, on average, 57% of jobs are susceptible to automation; however, this number rises to 69% in India and 77% in China.

Jobs in transportation, logistics, and administrative support are some of the most susceptible. Jobs at low risk of automation consist of generalist occupations requiring knowledge of human heuristics (problem solving), and occupations involving the development of novel ideas and artifacts. In other words, the common denominator for low risk jobs is that they are intensive in social and creative skills.

The report emphasizes the importance of acquiring skills for future employment. The European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) estimated that, in the EU, nearly half of new job opportunities will require highly skilled workers. However, today’s technology sectors have not provided the same opportunities, particularly for less educated workers, as the industries that preceded them.

As such, this has caused a bit of a lag, and individuals may start (or already have started) falling behind.

The Solution

The report asserts that technological innovation will demand a new set of skills in the workforce. In anticipation of this, in order to prepare for the world of tomorrow, the report calls for an increased investment in education.

Education, the authors say, is one of the most effective policies to offset the risk of automation.

It’s not a simple task by any means. Training to become, for example, a data scientist requires an advanced quantitative degree in mathematics and statistics, computer science, or engineering (88% of the people applying for data scientist roles have at least a Master’s degree and 46% have a PhD).

Acquiring such high skills obviously requires a number of years in training on the individual’s part, but it also requires a serious investment in education by the society in question, as individuals need to be prepared for the work that is ahead of them.

On top of this, it’s difficult to anticipate where technological innovations may lead to job creation. How can we train people for jobs that don’t yet exist? Simply put, we need to teach new skills.

So what skills should we concentrate on in order to ensure we have a good job in this highly automated future?

According to the report, a greater emphasis on skills such as literacy and numeracy are needed. There will also be a need for individuals who are able to create and program new technologies as these technologies emerge. In addition, more focus on STEM skills is needed, followed by an increase in soft skills (skills that allow individuals to interact with others effectively), and a move toward active learning.

The report summarizes the areas of interest thus: “Focus less on pure academics, and more on creativity and presentation skills. The enormous likelihood is that however good you are at STEM subjects, there are likely to be people in the world who are infinitely better than you — this is to say nothing of the computers that will eventually take over all STEM related roles. Communication skills, creativity and the ability to adapt to change are hugely more valuable and a much better differentiator medium-term.”

Finally, Frey and Osborne identify four key characteristics humans possess that cannot be programmed:

- Originality: “The ability to come up with unusual or clever ideas about a given topic or situation, or to develop creative ways to solve a problem.”

- Service Orientation: “Actively looking for ways to help people.”

- Manual Dexterity: “The ability to quickly move your hand, your hand together with your arm, or your two hands to grasp, manipulate, or assemble objects.”

- Gross Body Coordination: “The ability to coordinate the movement of your arms, legs, and torso together when the whole body is in motion.”

In his book Humans are Underrated: What High Achievers Know That Brilliant Machines Never Will, Geoff Colvin states that our inbuilt propensity for social interaction, communication, and empathy is what makes people special — something that machines can never replace.

So, there is hope.