Potential Hazards

Gene editing is a relatively new technology, and no other method currently available is as fast, precise, and efficient as CRISPR-Cas9. It has had unprecedented success in a number of fields, particularly in medicine—allowing scientists to edit HIV out of living organisms and engineer an end to malaria through the modification of mosquitoes.

Chinese scientists asserts that they've already used CRISPR on a human being, and clinical trials are in the mix in many locals (including the United States). Given the expected widespread use of CRSIPR in the world of tomorrow, researchers from the Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) are offering a word of caution. A study published in the journal Nature Methods revealed that CRISPR-Cas9 can lead to unintended mutations in a genome.

“We feel it’s critical that the scientific community consider the potential hazards of all off-target mutations caused by CRISPR, including single nucleotide mutations and mutations in non-coding regions of the genome,” co-author Stephen Tsang, from CUMC, said in a press release.

In the study, Tsang's team sequenced the genome of mice that they had previously used CRISPR on in an attempt to cure their blindness. They looked for all possible mutations, even those that might have changed just a single nucleotide. The researchers discovered a staggering 1,500 single-nucleotide mutations and over 100 larger deletions and insertions in the genomes of two of the recipients.

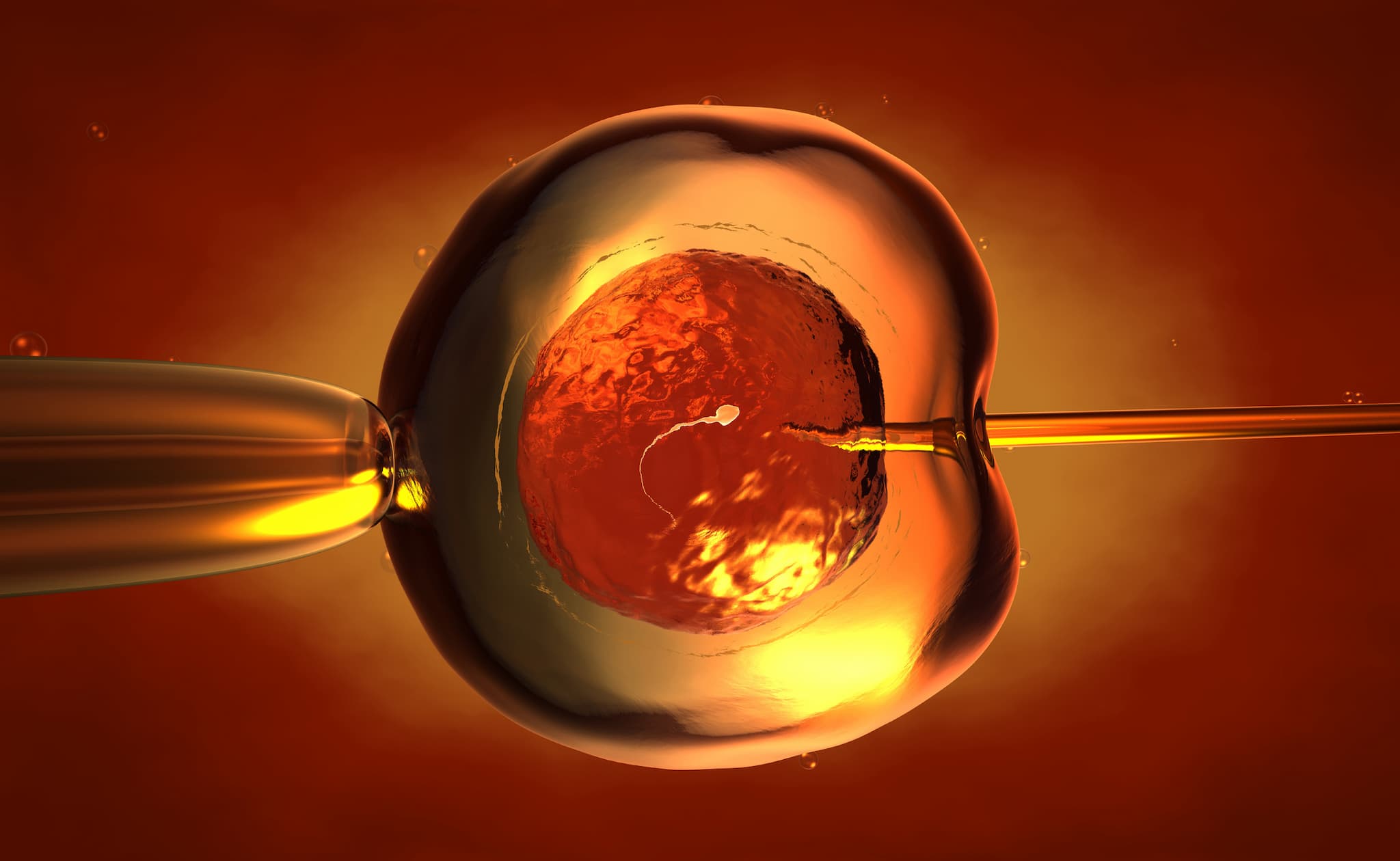

To better understand the difference between single nucleotide changes and larger deletions, see the below infographic:

Refining Methods

The study isn't suggesting a wholesale ban on CRISPR—not even close. After all, CRISPR was found to be effective in the mice they used it on. Instead, the scientists are offering caution, and calling for a clearer method of checking for mutations, deletions, or insertions into genomes. They propose doing whole-genome sequencing instead of relying on computer algorithms, which didn't detect any of the mutations they discovered in the study.

"We hope our findings will encourage others to use whole-genome sequencing as a method to determine all the off-target effects of their CRISPR techniques and study different versions for the safest, most accurate editing," Tsang said.

“[P]redictive algorithms seem to do a good job when CRISPR is performed in cells or tissues in a dish, but whole genome sequencing has not been employed to look for all off-target effects in living animals,” added co-author Alexander Bassuk, from the University of Iowa.

The potential of the CRISPR-Cas9 system as a gene editing technology is undeniable. As previously mentioned, already, it has seen success in developing possible cancer treatments, in making animals disease-resistant, and has shown promise in even replacing antibiotics altogether.

It has also been used to program living cells into digital circuitry. Among its more exciting — and perhaps dangerous(?) — applications is nothing short of a Jurassic Park-esque revival of extinct species. There seems to be no limit to what CRISPR can do.

However, as this research reveals, in order to realize the full potential of gene editing, and to ensure that living organisms aren't harmed as a result of the edits that we make to DNA—the source code of life itself—we must advance slowly and with careful scrutiny.

Share This Article