Faint and Far

The discovery of galaxies orbiting the Milky Way isn’t new. They are called satellite galaxies and, so far we have observed 50 of them, 40 of which are faint. These faint galaxies are called dwarf spheroidal galaxies. Well, it turns out that there’s something even more faint than these. A team of scientists from a number of institutions discovered the faintest galaxy ever to be found using the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii.

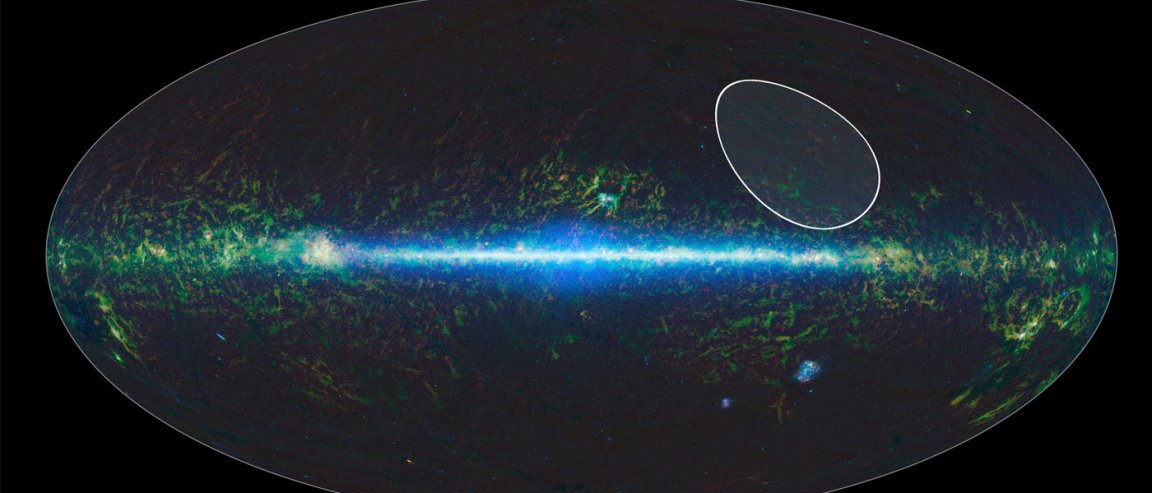

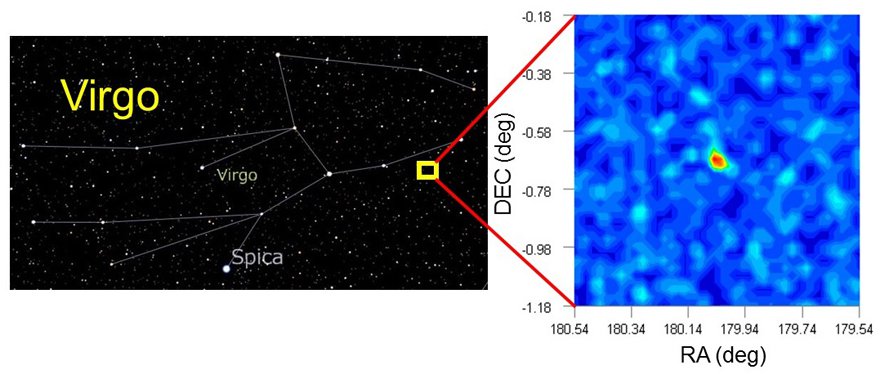

The previously hidden satellite galaxy has been named Virgo I, as it lies in the direction of the constellation Virgo in our night sky. What made detection possible is the Subaru Telescope’s large aperture and a tool called the Hyper Suprime-Cam (HSC). The HSC allowed the Subaru to scan a huge part of the night sky, searching for areas with high star density.

Virgo I lies around 280,000 light-years from our sun and about 248 light-years away. “Surprisingly, this is one of the faintest satellites, with [an] absolute magnitude of -0.8 in the optical waveband. This is indeed a galaxy, because it is spatially extended with a radius of 124 light years — systematically larger than a globular cluster with comparable luminosity,” said researcher Daisuke Homma of Tohoku University in Japan. That’s the faintest ever. Prior to its discovery, we could discover galaxies with absolute magnitudes no lower than -8.

The study was published in the Astrophysical Journal.

A light for dark matter

“[The discovery of Virgo I] implies hundreds of faint dwarf satellites waiting to be discovered in the halo of the Milky Way,” lead researcher Masashi Chiba said. However, it proves something more than just that. “How many satellites are indeed there and what properties they have, will give us an important clue of understanding how the Milky Way formed and how dark matter contributed to it,” Chiba added.

The ever-elusive dark matter has been the subject of many studies. Yet, despite such extensive study, the concept still remains to be proven. Virgo I could be a major clue in the quest toward proving the existence of dark matter. Supposedly, because of how dark matter behaves, our galaxy should have hundreds of orbiting satellite galaxies, a far cry from our current count.

Whatever the case may be, it looks like we’re about to discover some more satellites like Virgo I. Whether this proves that dark matter does exist, and validates our current theories about what holds our galaxies together, remains to be seen.