Lava Cake

Mars’ interior is harboring a huge secret.

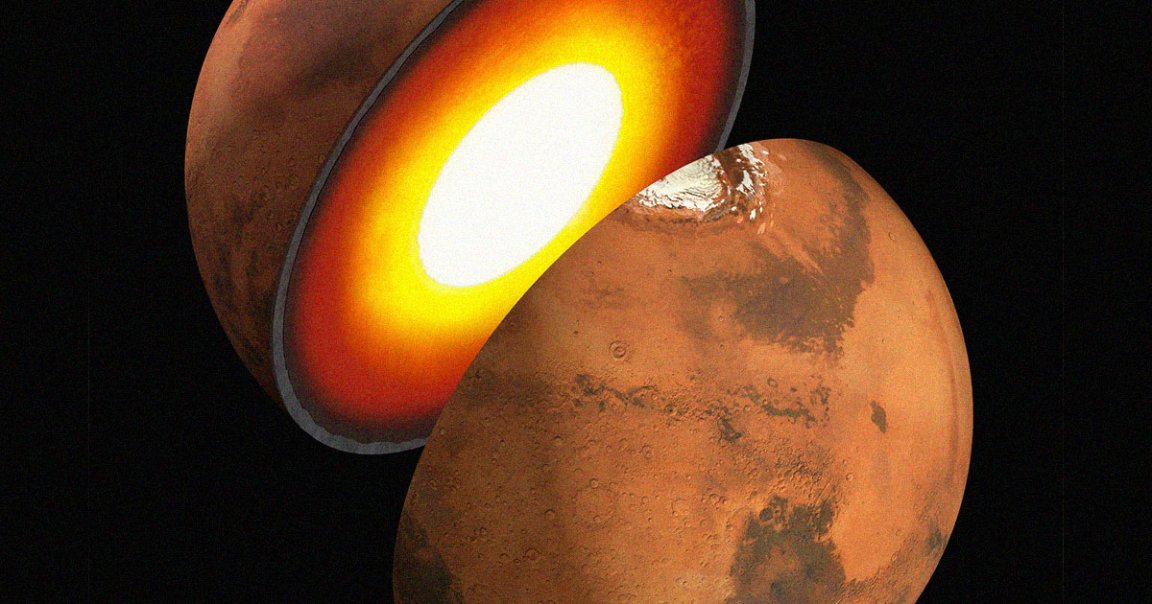

New analyses of seismic data from NASA’s InSight lander reveal that concealed beneath the Red Planet’s surface is a vast radioactive ocean of magma reaching up to 125 miles in depth — a layer totally unlike anything found in our own planet.

“It does not exist on Earth,” Amir Khan, lead author of one of the analyses and a geophysicist at ETH Zurich in Switzerland, told The New York Times.

The discovery of this magma sea, as detailed in a pair of independent studies published in the journal Nature, could explain why previous calculations estimated that Mars’ core was unusually large and lower in density, a puzzling and hotly debated conclusion that didn’t have some scientists convinced.

However, new evidence suggests that its core may be small and dense like our own world’s, and that the magma layer was obfuscating its actual size. Even better, these findings call into question the history of Mars’ evolution, and possibly of other terrestrial worlds.

Deeper Insight

Scientists have relied on InSight to detect seismic tremors on Mars since 2018. But for years, none of these so-called “marsquakes” penetrated deep enough to reveal anything about the planet’s core.

With the data that was available, scientists estimated that the core was around 1,150 miles in radius, suggesting it was not dense enough to be a homogeneous ball of liquid iron. Instead, there had to be a greater share of lighter elements like carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen in the mix, too.

This conclusion didn’t sit right with some scientists. Those lightweight elements should have been vaporized ages ago by either the heat of the extensive magma layer or the Sun.

But in August and September of 2021, two huge tremors, one caused by a large meteorite impact, shot powerful vibrations straight into the center of the planet.

These massive shocks were just what the researchers needed to illuminate Mars’ murky interior. Feeding that seismic data into advanced computer simulations revealed that the core’s radius was a tighter and much more reasonable 1,050 miles — suggesting that it is, in fact, almost pure liquid iron.

“This means that the average density of the Martian core is still somewhat low, but no longer inexplicable in the context of typical planet formation scenarios,” said Paolo Sossi, co-author of one of the studies and a planetologist at ETH Zurich, in a statement about the work.

Too Cool

But where one mystery is solved, another one rears its head.

Mars, now barren and exposed, once had a protective magnetic field around four billion years ago. Scientists believed that, like with Earth and other terrestrial worlds, the gradual cooling of its core caused the rest of the liquid iron to swirl, generating a magnetic field.

Yet, if the magma sea was present, it would have been too warm for the core to cool. In other words, something else was responsible for Mars’ magnetic field — and as of right now, scientists still don’t know what allowed it to exist.

More on Mars: Scientists Puzzled by Sudden, Super-Loud Rumble Inside Mars