Slow Jams

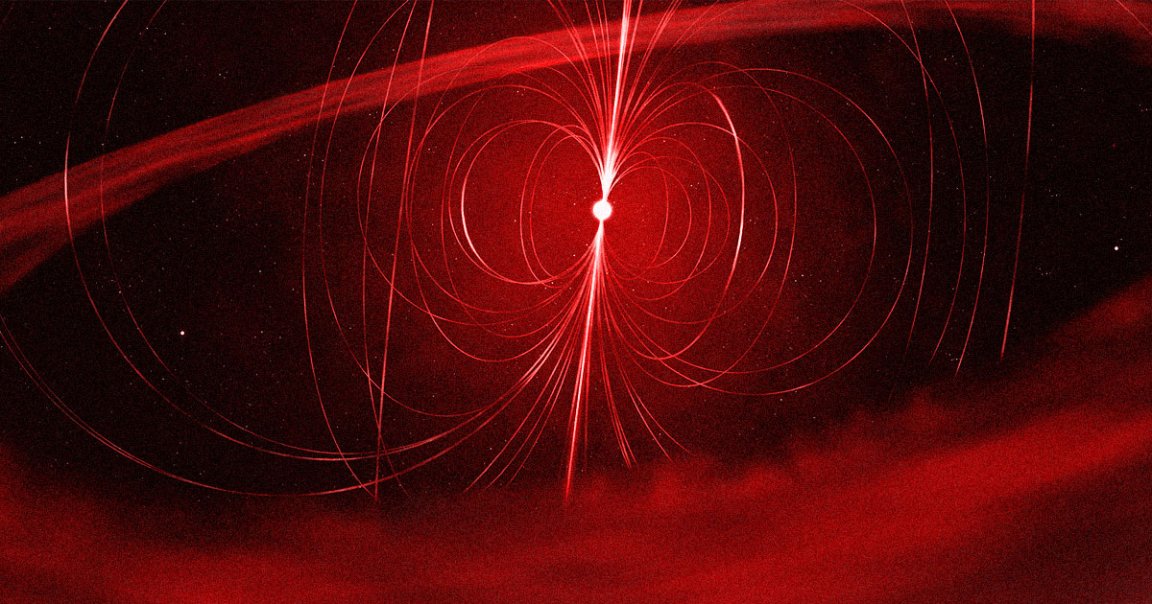

Astronomers have long been observing pulsars, which are highly magnetized neutron stars that rotate and shoot out beacons of energy, much like a lighthouse.

These repeating radio signals are detected back here on Earth as powerful and surprisingly regular blips — at least until they inevitably slow down and die.

Now, a team of researchers has discovered a different kind of pulsar called a magnetar, which sends out even more powerful blasts of radio waves that repeats every 22 minutes — an astonishingly long period for such a celestial object.

In fact, as the astronomers detailed in a new study published in the journal Nature, this particular magnetar dubbed GPM J1839−10 has been blasting out five-minute-long signals from 15,000 light-years away since 1988 — and at an incredible degree of accuracy, down to the tenth of a millisecond.

Never Give Up

And it’s seemingly not slowing down, confounding our preexisting notions about pulsars.

“This remarkable object challenges our understanding of neutron stars and magnetars, which are some of the most exotic and extreme objects in the Universe,” said lead author Natasha Hurley-Walker, a radio astronomer at Curtin University in Australia, in a statement.

In other words, the magnetar should’ve died a long time ago, and its “radio emission should only be visible for a few months to years — not 33 years and counting,” as Hurley-Walker explained in a widely-cited piece for The Conversation.

“So when we tried to solve one problem, we accidentally created another,” she wrote. “What are these mysterious repeating radio sources?”

The astronomers are now left with an even bigger puzzle. What is J1839−10? Could it really be a magnetar in spite of its astonishing longevity?

The discovery could force us to rethink what we know about the evolution of neutron stars. For now, Hurley-Walker and her team are hoping to detect more radio signals like it.

“That was quite an incredible moment for me,” Hurley-Walker recalled, referring to the moment she found evidence of the signal in data recorded back in 1988. “I was five years old when our telescopes first recorded pulses from this object, but no one noticed it, and it stayed hidden in the data for 33 years.”

“They missed it because they hadn’t expected to find anything like it,” she added.

More on pulsars: Pulsar Devours Neighbor, Becomes Heaviest Neutron Star Ever Observed