Wind Tunnel

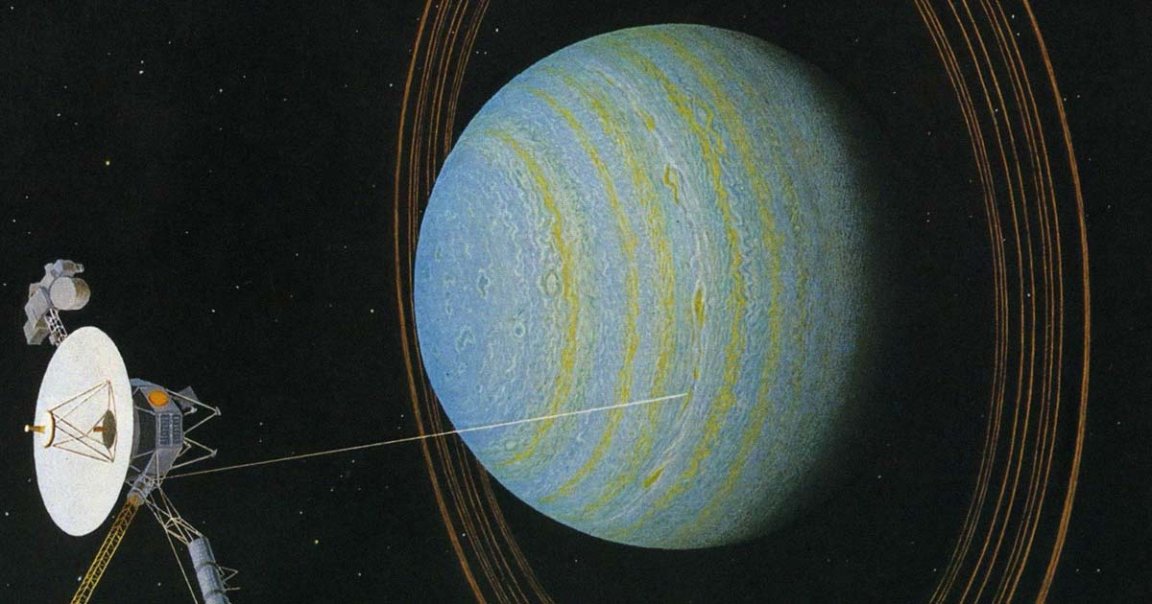

Scientists have found that a “rare intense wind event” during NASA’s Voyager 2 flyby of Uranus in 1986 may have seriously messed with our understanding of the planet.

And yes, we admit, the jokes practically write themselves.

But the research is very real. As detailed in a new paper published in the journal Nature Astronomy, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab scientist Jamie Jasinski and an international team of researchers found that our current understanding of Uranus may be based on data collected during an unusual period of time when Uranus’ magnetosphere was in an “anomalous, compressed state,” which only occurs “less than five percent of the time.”

In other words, our current understanding of the distant planet may be far more limited than we thought because the Sun was pelting Uranus with solar weather at the time.

Letting Rip

Jasinksi reexamined the data collected by Voyager 2 during its 1986 flyby and found that the probe had examined Uranus shortly after an intense solar wind event, which saw a huge surge of charged particles blast its way from the Sun.

The event compressed the planet’s magnetosphere, they found, causing it to deform into a significantly asymmetrical shape that appeared to lack plasma.

“We postulate that such a compression of the magnetosphere could increase energetic electron fluxes within the radiation belts and empty the magnetosphere of its plasma temporarily,” the researchers wrote in their paper.

Even if Voyager 2 had come to visit a mere week earlier, the researchers suggest, it would have found a far more recognizable magnetosphere, like those surrounding other planets in our solar system, including Jupiter, Saturn, and Neptune.

“Owing to the variation of the solar wind at Uranus, we suggest that there may be two magnetospheric cycles during solar minimum,” the researchers suggested, referring to the calmest period of the Sun’s 11-year solar cycle.

Intriguingly, Uranus’ two most distant moons Titania and Oberon may be orbiting the planet outside the magnetosphere, which could give astronomers an unprecedented look at their subsurface oceans without any electromagnetic interference.

In short, we shouldn’t draw any definitive conclusions from NASA’s flyby almost 40 years ago.

“We highlight that our understanding of the Uranus system is highly limited, and our analysis shows that any conclusions made from the Voyager 2 flyby are similarly tentative,” the researchers conclude in their paper. “We suggest that discoveries made by the Voyager 2 flyby should not be assigned any typicality regarding Uranus’s magnetosphere.”

More on Uranus: The Mighty James Webb Peers Directly Into Uranus