Swimming in Circles

Last month, China sent four small zebrafish as stowaways to its Tiangong space station.

And so far, according to the state-owned Xinhua News Agency, the striped catch is thriving in the microgravity environment of its celestial space aquarium. That’s despite the astronauts on board the station observing the fish “showing directional behavior anomalies, such as inverted swimming and rotary movement.”

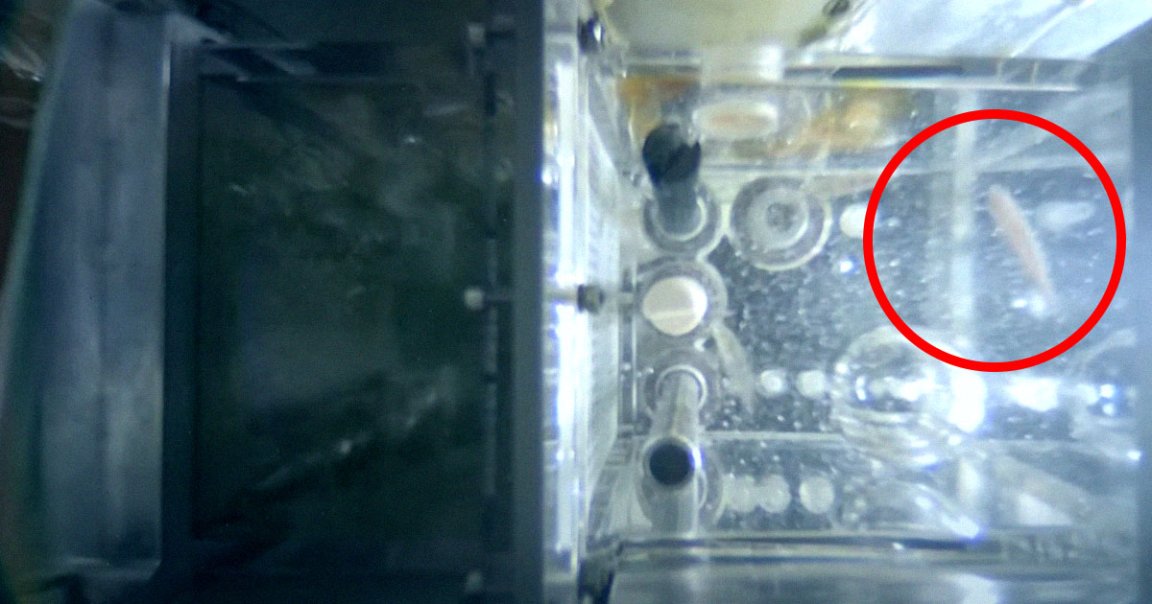

In a video released by the China National Space Administration, the fish are swimming in all sorts of different directions inside a glass cube, seemingly struggling to tell which way is up.

They even went through rigorous tests before getting their astronaut wings.

“Meanwhile, like astronauts, zebrafish need to pass through rounds of selection to become ‘aquastronauts,'” Chinese Academy of Sciences hydrobiology researcher Wang Gaohong told Xinhua.

But their struggles serve an important purpose. Scientists are hoping to study the impact of microgravity on vertebrae such as zebrafish by focusing on their behavior, growth, and development by analyzing water samples and fish eggs during the experiment.

The data could shed further light on how space and cosmic radiation can impact much larger vertebrae like humans, which could have important implications for our future efforts to venture further into space.

Spaced Out

This is not the first time humans have had to entertain fish in space. In 1973, NASA launched two mummichog fish into space, alongside a container of 50 fish eggs, according to a 2016 Scientific America article, making them the first fish in space.

Upon arriving at the NASA Skylab space station, the fish “swam in elongated loops as though they were the spinning hands of a Salvador-Dali created clock,” the article reads. “Without gravity the fish didn’t know which way was up.”

Eventually, the fish oriented their backs to the lights inside the Skylab, using light as a way to direct themselves. And the hatchlings that came on board as eggs also used light to orient themselves.

But despite what looked to be a successful introduction to the cosmos, fish — like humans — suffer from bone density loss as the Japanese discovered when they sent zebrafish and medaka, a type of fish often found swimming in rice fields in Asia, to the International Space Station in 2012.

In other words, further studying the behavior of fish in a near-weightless environment could prove invaluable to our understanding of the effects of space travel on human health.

More on fish: Scientists Suggest Farming Fish on the Moon