Irony Deficiency

Jason Allen, the AI “artist” whose image he created with Midjourney won a fine arts competition two years ago, is still mad that the government won’t let him copyright his opus — and, in an amazing lack of self-awareness, is also crying that his work is being stolen as a result.

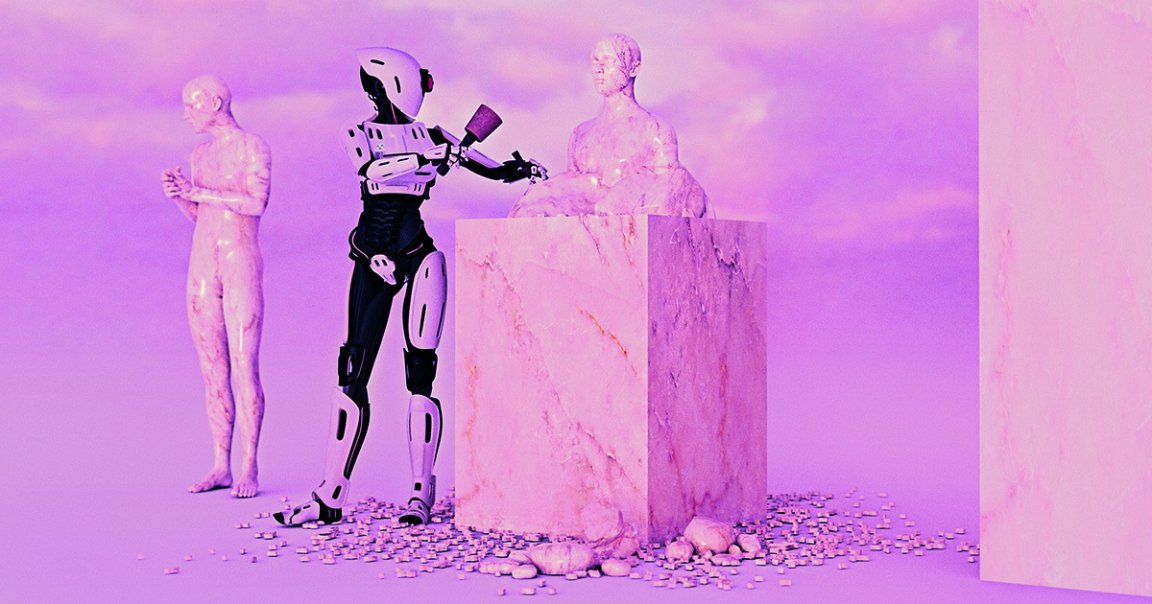

The prizewinning image, “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial,” was deemed to not wholly exhibit human authorship because a significant amount of it — as Allen himself disclaimed — was AI-generated, the US Copyright Office said in a ruling last September. As such, Allen could only claim credit for specific portions of the image that he created with Photoshop — not the thing as a whole.

Now he’s making another appeal, Creative Bloq reports, complaining that he’s losing money to the tune of “several million dollars” because, without a copyright, his work is being used without his approval. Does this argument ring any bells?

“The Copyright Office’s refusal to register Theatre D’Opera Spatial has put me in a terrible position, with no recourse against others who are blatantly and repeatedly stealing my work without compensation or credit,” Allen said, as quoted by Creative Bloq.

Theft Machines

We’re sure the irony of Allen’s perceived grievances isn’t lost on any artists out there. By and large, image-generating AI models were trained on countless artworks that were scraped — or arguably, stolen — from the internet without permission or compensation.

The upshot is that these AI services, which garner millions of dollars from investors on top of what people pay to use them, either amalgamate or outright ape existing art without any money, let alone credit, going to the original creators.

For these reasons, Midjourney, the AI service Allen used, is being sued by a group of artists who argue that the company committed copyright infringement for ingesting their artwork.

The ongoing lawsuit, which also targets Stability AI and several other AI firms, was allowed to proceed last month after the defendants tried to get the case dismissed.

Umpteenth Time’s the Charm

With that and many other potentially precedent-setting cases hanging in the balance, this remains a legally murky area. Trying his luck again, Allen argues in his latest appeal that the 624 times he had to revise his prompts took him at least 110 hours of work, per Creative Bloq. To him, his prompt engineering is comparable to a director creating a whole film. (Related: in the world of filmmaking, needing 600+ takes to get a scene right would get you laughed out of the business, unless your last name was Kubrick.)

“The refusal of the US Copyright Office to recognize human authorship in AI-assisted creations highlights a critical issue in modern intellectual property law,” Tamara Pester, an IP attorney serving as Allen’s lawyer, told Creative Bloq. “As AI continues to evolve, it is imperative that our legal frameworks adapt to protect the rights of those who harness these technologies for creative expression.”

Whether this will sway the Copyright Office remains to be seen. But what’s at question here is if it counts as his original work, and not necessarily however long he spent prodding an AI model.

More on AI: Editors of Sci-Fi Magazine Disgusted as They Realized Submissions Were Filling With AI Slop