The Oort cloud is traditionally thought of as a vast shell of perhaps trillions of icy objects encasing our solar system, serving as the final boundary between us and the dark reaches of interstellar space.

But it’s not a homogenous mass. In reality, astronomers don’t yet have a complete picture of what it looks like — and are only beginning to glimpse just how complex its makeup might be.

Now, in a new study set to be published in The Astrophysical Journal, a team of researchers from the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado say they’ve discovered a fascinating aspect about the Oort cloud’s interior that can change how we view its overall shape: a spiral structure that’s similar to the spiral arms of our galaxy.

At a heliocentric distance ranging from 10,000 to 100,000 astronomical units — each unit being equal to the distance between the Sun and the Earth — the Oort cloud is both incredibly vast and totally out of reach. There’s little sunlight to speak of, and observing the cloud is almost prohibitively challenging from such distance.

The Oort cloud’s remoteness also means the pull of the Sun’s gravity is relatively weak. Instead, astronomers believe that its untold number of objects are largely governed by what’s dubbed the “galactic tide” — the gravitational pull of massive objects like black holes in our galaxy’s center, which ebbs and flows as our solar system ambles through the Milky Way. (For objects near the Sun, like planets, the tide’s effect is largely overpowered by the star’s gravity.)

This is what the researchers homed in on: the effects of the galactic tide. To do that, they observed long-period comets, which originate from the Oort cloud and barge into the solar system’s interior after being displaced by the galactic tide, providing a rare glimmer of the cloud’s goings-ons. Specifically, some of the comets come from a denser region known as the “inner” Oort cloud, which has long been pictured as a flat disk sheltered within the greater cloud’s spherical shell, according to the researchers.

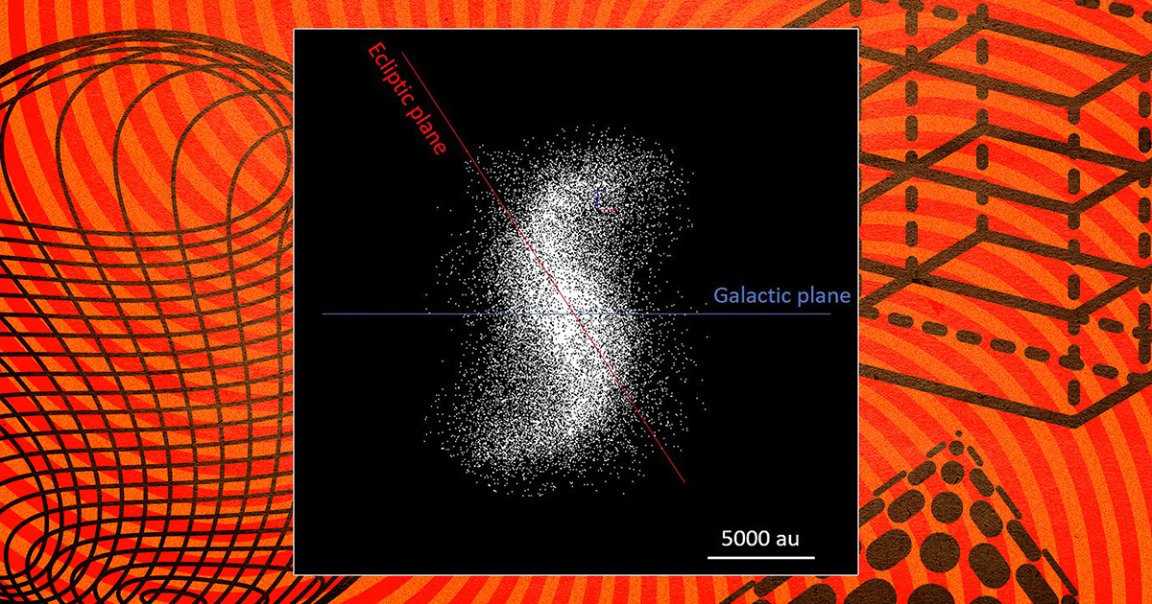

Feeding data on these comets along with other observations into an advanced model on NASA’s Pleiades supercomputer, the researchers found evidence that the “flat disk” image could be outdated. It’s more likely a “slightly warped” disk, they found, approximately 15,000 AU across.

“The disk, when viewed from a distance, would appear as a spiral structure with two twisted arms,” the authors wrote. Those “arms” resemble the elongated structures of a spiral galaxy, like our very own Milky Way.

At an epic timescale “comparable to the age of the solar system,” which is 4.6 billion years old, the researchers believe that the spiral arms formed when “small bodies” were pushed out of the system’s interior by planets to around 1,000-10,000 AU, where they would “orbitally evolve by the Galactic tide.” That suggests that the spiral structure has been here almost since our system’s beginning, retaining its shape all the while.

To bear out the findings, the researchers hope that one day we’ll be able to directly observe some of the objects lurking within the inner Oort Cloud — but the technology required to do that is likely a long way off.

More on space: We’re So Screwed, Even That “City Killer” Asteroid Doesn’t Want to Destroy Earth Anymore