Absolute zero is the temperature (-273.15C) at which all motion in matter stops and is thought to be unreachable. But recent experiments using ultracold atoms have measured temperatures that are, in fact, negative in absolute temperature scale.

The journey there, however, is quite the opposite to what you might expect. Simply removing heat from the equation to make things colder and colder is not the answer. Instead, you need to heat things hotter than infinitely hot!

Understanding temperature

The concept of temperature is intimately connected to the concept of disorder. Typically, a high degree of order corresponds to a low temperature. A perfect order is tantamount to absolute zero and a maximum possible disorder corresponds to an infinite temperature.

Ice crystals are more ordered than boiling water and, as intuition tells us, ice is indeed colder than hot water. By adding more energy in the water molecules will cause their motion to become ever more chaotic and disordered, thus increasing their temperature.

But under certain very special circumstances, a system may become more ordered when more energy is added beyond a critical value which corresponds to an infinite temperature.

Such a system is then characterised by negative absolute temperature. Continuing to add more energy in such a system would ultimately render it perfectly ordered at which point it would have reached negative absolute zero.

If the positive absolute zero is the point at which all motion stops, then the negative absolute zero is the point where all motion is as fast as it possibly can be.

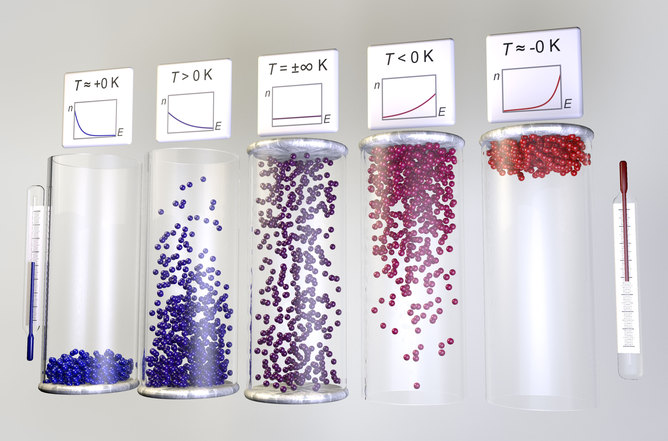

In the image (above), at positive absolute zero the blue marbles on the left have minimum possible energy and they are sitting in the bottom of the container whereas at negative absolute zero, the now red hot marbles on the right have the maximum possible energy and are sitting at the ceiling of the container.

Since at negative absolute temperatures the average energy of the particles is higher than at any positive absolute temperature of the same system, it means that at negative absolute temperature the system is in fact hotter (in the sense that it is more energetic) than what it could be at any positive absolute temperature.

Sounds impossible? Well, let us explore further.

Into the maelstrom

The concept of negative absolute temperature was originally introduced by Nobel Prize winning chemist and physicist Lars Onsager in the context of turbulence in fluids. Notwithstanding centuries of research initiated by Leonardo da Vinci, turbulence itself remains an open problem to date.

Onsager predicted that in turbulent two-dimensional fluid flows, small eddies – rather than fading away – would spontaneously begin to grow in size forming ever larger and larger giant vortex structures. This process would then lead to the emergence of order out of turbulence.

Such enormous vortices that bring about order amid chaos are so energetic that the system reaches temperatures hotter than hot and enters the absolute negative temperature regime (red marbles). The enormous turbulent whirlwinds would support extremely fast fluid motion and correspondingly high energies of the system.

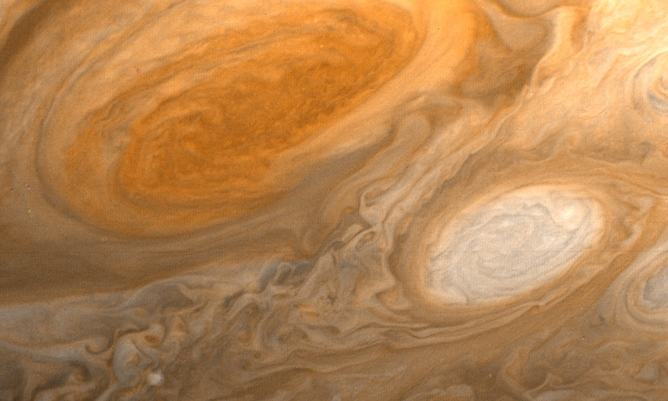

Such a phenomenon is thought to underlie many naturally occurring maelstroms such as the Gulf Stream or the Great Red Spot on the surface of Jupiter.

Now our work, published in the Physical Review Letters, has predicted that similar Onsager vortices characterised by absolute negative temperature could also emerge in planar superfluids. These are fluids with the ability to flow without friction.

Like classical viscous fluids, superfluids too can be made turbulent. Studies of the resulting “superfluid turbulence” are anticipated to yield new insights to Onsager’s original predictions of absolute negative temperatures and emergence of order out of chaos.

But following the recent experimental observation of negative absolute temperatures of ultra-cold atoms, the very existence of thermodynamically consistent negative temperatures has been questioned. While the debate continues, it is clear that once the dust settles, many textbooks should be revised.

Nevertheless, whatever temperature should be used for describing certain experiments, the fact remains that such novel states of matter are a feat of experimental physics and may potentially be useful for applications of emergent future technologies such as Spintronics or Atomtronics. These propose replacing the information carriers (electrons) used in electronics by more efficient quantities such as spins, which are sort of elementary magnets, or whole atoms.

Meanwhile, we may rest assured that no thermometer should ever be able to reach absolute zero — positive or negative.

Tapio Simula receives funding from Australian Research Council (ARC). He is affiliated with American Physical Society (APS). He works for Monash University. This article was provided by The Conversation.