NASA Wants Spacebound Bacteria

NASA is sending samples of bacteria into low-Earth orbit in order to research methods of keeping astronauts healthy while they’re far away from home. The E. coli Anti-Microbial Satellite (EcAMSat) is set to investigate how well antibiotics can combat the bacteria while in space.

It’s thought that E. coli and other similar bacteria might be subject to stress when put under the conditions of microgravity. This would trigger their defense systems, making it more difficult for antibiotics to fight them off, not unlike the way that bacteria on Earth develop a resistance to such treatments – as such, this research might help improve our ability to produce such medicine for terrestrial use, also.

“If we find resistance is higher in microgravity, we can do something, because we’ll know the gene responsible for it, and be able to design countermeasures,” said A. C. Matin, the principal investigator on the EcAMSat project at Stanford University in California, according to a report from Space Daily. “If we are serious about the exploration of space, we need to know how human vital systems are influenced by microgravity.”

Healthcare for Astronauts

As astronauts go on longer missions to more distant destinations – for instance, the oft-touted hypothetical mission to Mars – it’s going to become increasingly important that they can have access to medicine off-world. EcAMSat will contribute to that capability.

The strains of E. coli that are being used as part of the project are responsible for urinary tract infections, which are among the various different ailments that can potentially affect astronauts in space. The results of the study will give mission planners more information about the proper dosage of medicine required to combat an infection.

EcAMSat is autonomous, and will operate independently once ground controllers and crew on the International Space Station collaborate to send it into orbit. Students at Santa Clara University will be tasked with monitoring its activity, handling mission operations, and receiving data.

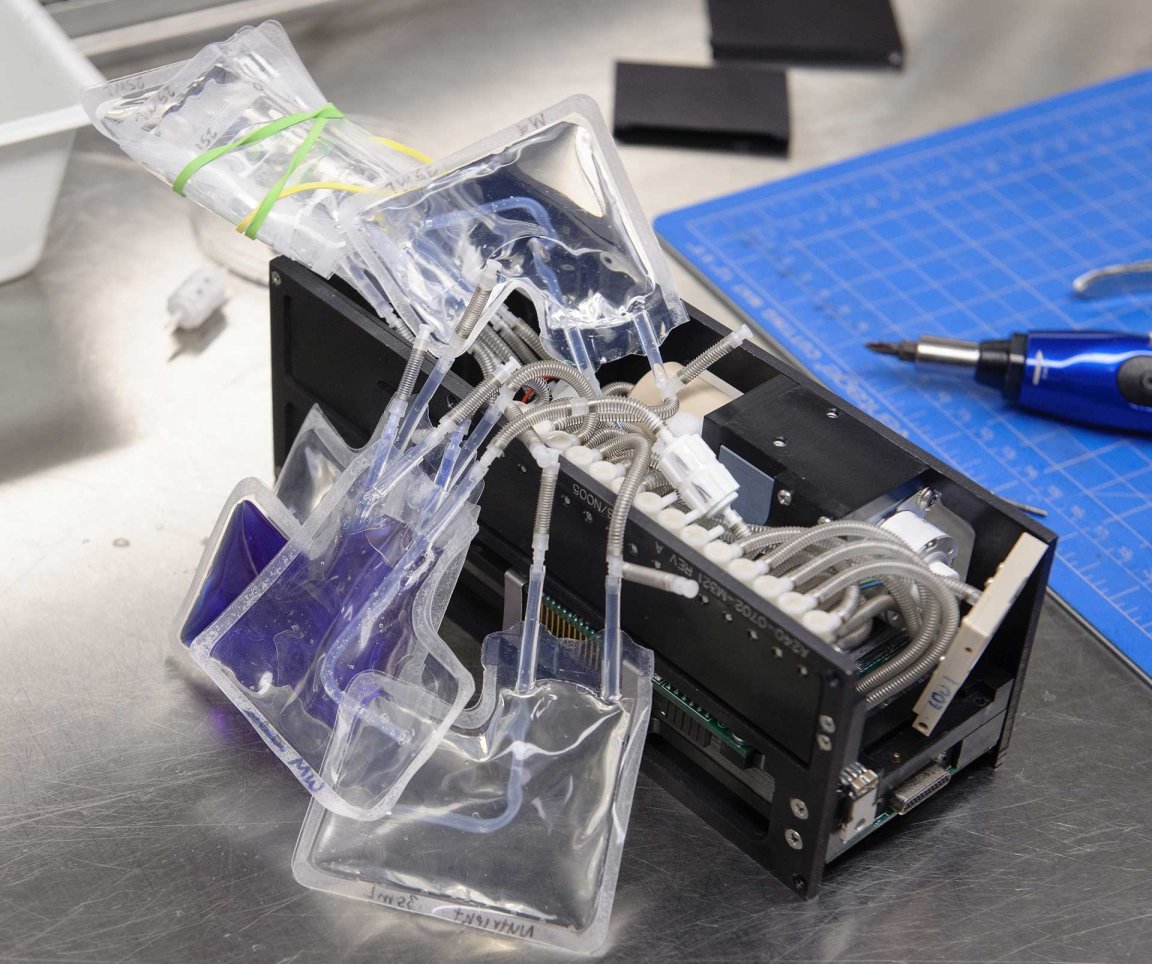

The dormant E. coli will be awakened via a fluid packed with nutrients, as the temperature of their containers is adjusted to that of the human body. The samples will then be administered with different dosages of antibiotics. Two types of E. coli are set to be compared, one that bears a naturally occurring gene that helps it resist antibiotics, and another which does not.

The bacteria will be mixed with a blue dye that turns a deeper shade of pink depending on how many cells remain active and viable. If it remains blue, it means that the antibiotic dosage has killed off most of the cells. The experiment is set to last for 150 hours, at which point the data will be transmitted down to Earth via radio.

While the main priority is this research into the effectiveness of antibiotics in space, a successful voyage will also help demonstrate the capabilities of the tiny satellite, which is approximately the size of a shoebox.

“Though EcAMSat will only fly this once, many of its components may embark on a different mission: life detection in the solar system,” said Tony Ricco, Ames’ chief technologist for the mission, in a report published by NASA. “Using sensors and the microfluidics technology from EcAMSat, NASA is developing the technology needed to look for life on moons such as Enceladus and Europa – ocean worlds covered by icy crusts.”