Eliminate Scarring

Scars are a normal part of life — for now, anyway. In the future, that might not be the case, as researchers have developed a method to eliminate scarring by prompting wounds to heal as normal skin rather than as scar tissue.

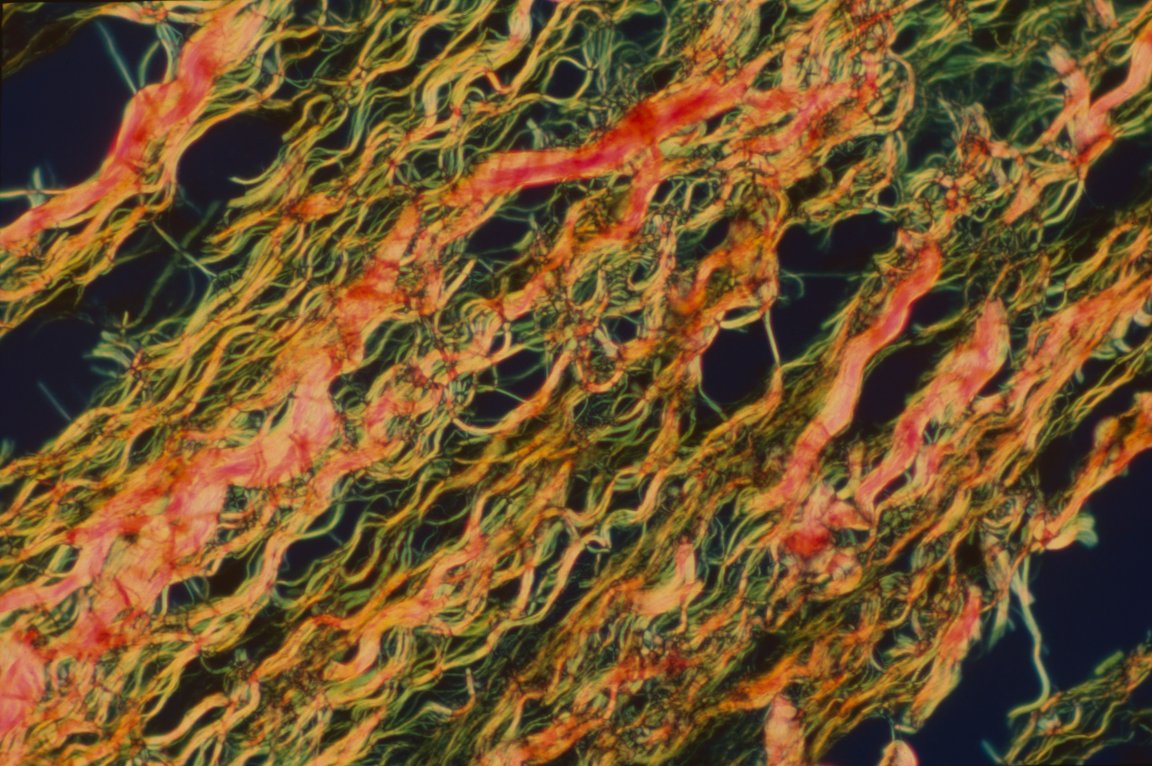

Scar tissue looks different than normal skin because it doesn’t feature any fat cells or hair follicles. Smaller cuts are filled in with skin that contains fat cells called adipocytes, which allows it to blend in with the surrounding area. However, this isn’t the case for scar tissue, which is largely comprised of myofibroblasts.

This research indicates that we might be able to convert myofibroblasts into adipocytes, converting scar tissue to look like normal skin. Previously, this conversion was thought to be possible only in fish and amphibians.

The study, published in Science, builds upon previous research that established a link between the way that fat cells and hair follicles developed in the regenerated skin. Both would form separately, but not independently, with the hair follicles always appearing first.

This prompted the team to try inducing the growth of hair follicles in scar tissue that was being formed in samples of skin taken from mice and humans. Hair follicles were seen to release a signaling protein known as Bone Morphogenetic Protein during their development, which converted myofibroblasts to adipocytes.

Improved Results

These results are an improvement over currently available cosmetic surgery, which can make scars less visible but cannot actually eliminate scarring.

“Previous approaches to scar-reducing therapies focused on minimizing the size of the scar, but not eliminating it all together,” Maksim Plikus of the University of California, Irvine, a co-author of the study, told Futurism. “We observe regeneration of completely new fat cells from myofibroblasts, the principal cell type that causes scarring. This means that instead of just being reduced, scar tissue can be eliminated, replaced by normal tissues via the regeneration mechanism.”

However, there are some limitations to the procedure, at least in its current form. In mouse wounds, there’s a window of opportunity for the scars to be addressed, which seems to fall between day 15 after the injury (when new hair follicles start to regenerate) and day 28 (when fat regeneration is completed).

“The time window for inducing regeneration in wounds is fairly long, which is a great news for potential future regeneration-inducing therapy,” Plikus noted, acknowledging that further testing will be required to assess whether the window can be extended beyond 28 days after the injury was sustained. It’s not yet clear whether it will be possible to modify the therapy for use on older scars.

Furthermore, there are important differences between the skin of humans and mice that warrant further testing. Plikus wrote that the regeneration inducing signaling molecules observed in mice still have to be validated in human skin wounds, for instance.

The therapy has been demonstrated in human skin samples, but there’s a way to go before it can be performed on a living person’s wound. Still, it’s an exciting development that shows just how much we have to learn about our own skin. “Our research shows that adult skin in mammals has much broader regenerative potential than previously assumed,” Plikus said.