BUILDING AN ELECTRONIC KIDNEY

Scientists at Vanderbilt University have developed a first-ever implantable artificial kidney. The artificial kidney contains a microchip filter and living kidney cells that can function using the patient’s heart, and this bio-synthetic kidney acts like the real organ, removing salt, water and waste products to keep patients with kidney failure from relying on dialysis.

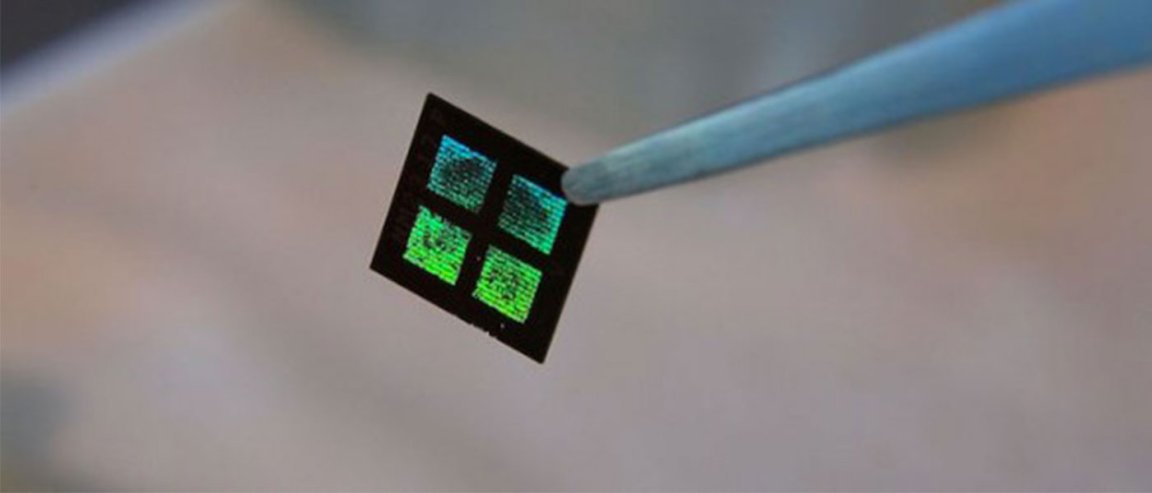

The key to this new development is a breakthrough in the microchip itself, which uses silicon nanotechnology. “[Silicon nanotechnology] uses the same processes that were developed by the microelectronics industry for computers,” said Dr. William H. Fissell IV, who led the team that developed the device.

The microchips are affordable, precise, and function as an ideal filter.

Each artificial kidney will contain 15 microchips layered on top of each other. These chips will work as filters and also act a support system for the living cells needed. These living cells are kidney cells grown in a laboratory dish and nurtured to become a bioreactor of living cells. This membrane of living cells allows the device to distinguish between innocuous chemicals and harmful ones.

“Then they can reabsorb the nutrients your body needs and discard the wastes your body desperately wants to get rid of,” said Fissell.

The artificial kidney does not require any external power source and functions solely with the patient’s own blood flow; however, the challenge for the researchers is how to get blood to flow through a blood vessel and move through the device without any damage or clotting.

SOLVING A DONOR PROBLEM

To resolve this problem of blood clotting, Fissell and his team collaborated with Amanda Buck, a biomedical engineer, to figure out the potential areas in the device which could lead to blood clotting. With the help of fluid dynamics and computer models, Buck was able to streamline and refine the shape of the channels so that blood could flow smoothly through the device. 3D printing also allowed for immediate feedback on the resulting prototype and analysis of its performance.

Considering the extent of shortage in kidney donors, the device would alleviate the demand for organ transplants for kidney failure patients. This shortage is not without its victims. The National Kidney Foundation has estimated that in US alone over 460,000 have last-stage renal disease and that about 13 kidney patients die every day waiting for a kidney.

The U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network said that there are over 100,000 American transplant patients waiting for a new kidney with only less than a fifth receiving transplants last year. With more research, the device may give those on the waiting list a new hope.

Clinical studies are scheduled to begin near the end of 2017.