Artificial Ovaries

Researchers have demonstrated that lab-grown artificial ovaries could provide a better way of providing hormone replacement therapy for women. In a study published in Nature Communications, engineered ovaries were found to perform better than hormone therapy drugs in terms of improving bone and uterine health, as well as body composition.

Taking drugs to supplement natural hormones simply supplies a regular dosage each day. A cell-based system can respond to the body’s needs, which allows for the lowest possible dose to be administered while still giving the desired effect.

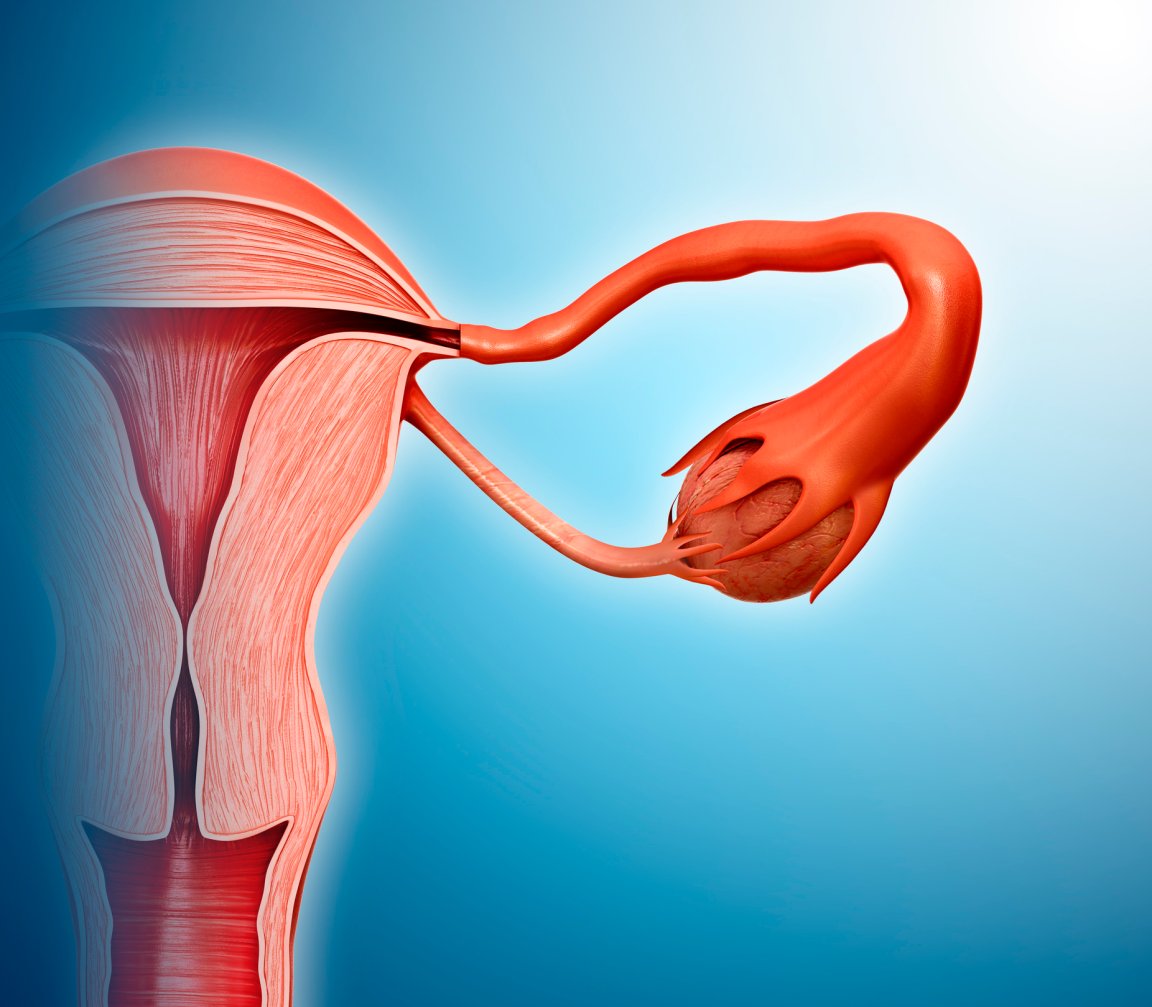

Loss of ovarian function can come as a result of surgical removal, chemotherapy, or menopause. As a result, women can suffer from a wide range of effects, including hot flashes, infertility, and a higher risk of osteoperosis and heart disease.

Current medications designed to respond to loss of female sex hormone production have been linked to heart disease and breast cancer, so they’re not recommended for long term use.

Replace and Repair

The researchers isolated two cells found in ovaries – theca and granulosa – to engineer a bioartificial version. These cells were taken from healthy rats, then inserted into rats that had their ovaries removed. The implanted animals were compared to rats with normal ovarian function, rats that had not been treated, and rats who received a high or low dosage of existing hormone replacement drugs.

A loss of ovarian function typically leads to changes in body composition, and often weight gain. The artificial ovaries were able to maintain a lower level of body fat in the rats than the medication, in line with the animals whose ovaries were intact.

Another common side effect of low estrogen levels is poor bone health, which can lead to osteoporosis and fractures. Bone strength was improved in experimental rats thanks to the artificial constructs.

The team also looked at the impact on the animals’ genitals and urinary system, which are frequently affected by a loss of ovarian function. Uterine health in the animals administered with the new treatment was comparable to the control animals.

There are hopes that this technique could provide a safe alternative to today’s drugs, which will be all the more important as the population of older women continues to grow. However, there are several obstacles that need to be overcome before human trials begin.

“First, we need to confirm this proof-of-concept with a follow up study,” wrote Emmanuel C. Opara, senior author on the study and professor at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, in an email to Futurism. “In which the cells to engineer the constructs are obtained from a different strain of rats as the ones that receive them in order to determine if the cell-based approach may be applicable in the scenario of using cells donated by unrelated female donors in patients requiring the treatment.”

Assuming the results of that study are promising, the approach would be tested in a large animal model such as a monkey, ahead of a clinical trial. “The major obstacle is funding,” explained Opara. “Because these additional studies require a lot of money to complete.”