When Caleb Wilvich read about the first woman in the U.S. to have a baby via a uterine transplant in early December, they were stoked. Wilvich, who uses the pronoun “they,” has always wanted to give birth, and never had a uterus. Wilvich is 29 and works an office job in a suburb of Seattle; in their free time, they’re a piano player and an a capella singer. They identify as genderqueer and transfeminine, assigned male at birth and living in a more ambiguous, feminine gender today.

Their gender dysphoria, they tell me, “is hard to describe to a cis [non-trans] person.” Suffice it to say that being male-assigned, with a beard and leg hair, means it’s not easy for them to inhabit the body they imagine for themselves. “Since before puberty, I’ve wanted the ability to be able to just snap my fingers and become a cisgender woman. I don’t even care about conventional attractiveness.”

Coming out as transgender was a long process, but starting a couple years ago, Caleb began dressing feminine at work and using gender-neutral pronouns. But for them, the ideal of womanhood — the form of womanhood they have always wanted — includes being able to carry a child. “The whole process of building that bond with a child through this period of pregnancy, through the trauma and joy of childbirth, through being there from their first moments in the world… I have so many strong emotions come up when I imagine being able to do those things.”

Lots of trans women share this desire, and the online trans community was abuzz over the first successful birth in the U.S. from a uterine transplant in December. Trans women’s dream of carrying a baby fits into a larger dream: to be able to completely embody femaleness, all the way down to the ability to conceive. Uterus transplants are the first of what might be many technologies that will enable people with gender dysphoria to inhabit the form they truly desire.

The problem for the future is in deciding who should have access to that dream. Psychiatrists, doctors, and insurance companies are the gatekeepers of trans surgeries today, and for most trans people, surgery isn’t easy to access. “They’re probably never gonna let trans people do it,” says Wilvich of uterine transplants. “Even if we are allowed to, will any of us be able to afford it?”

Wilvich touches on one of the biggest questions facing the future of procedures for trans people: Who will be able to access them? Right now many insurance plans don’t cover gender confirmation surgeries at all. No one knows how many transgender people who want surgeries currently aren’t able to get them, a problem that even the most advanced, cutting-edge procedures can’t fix.

Uter-US

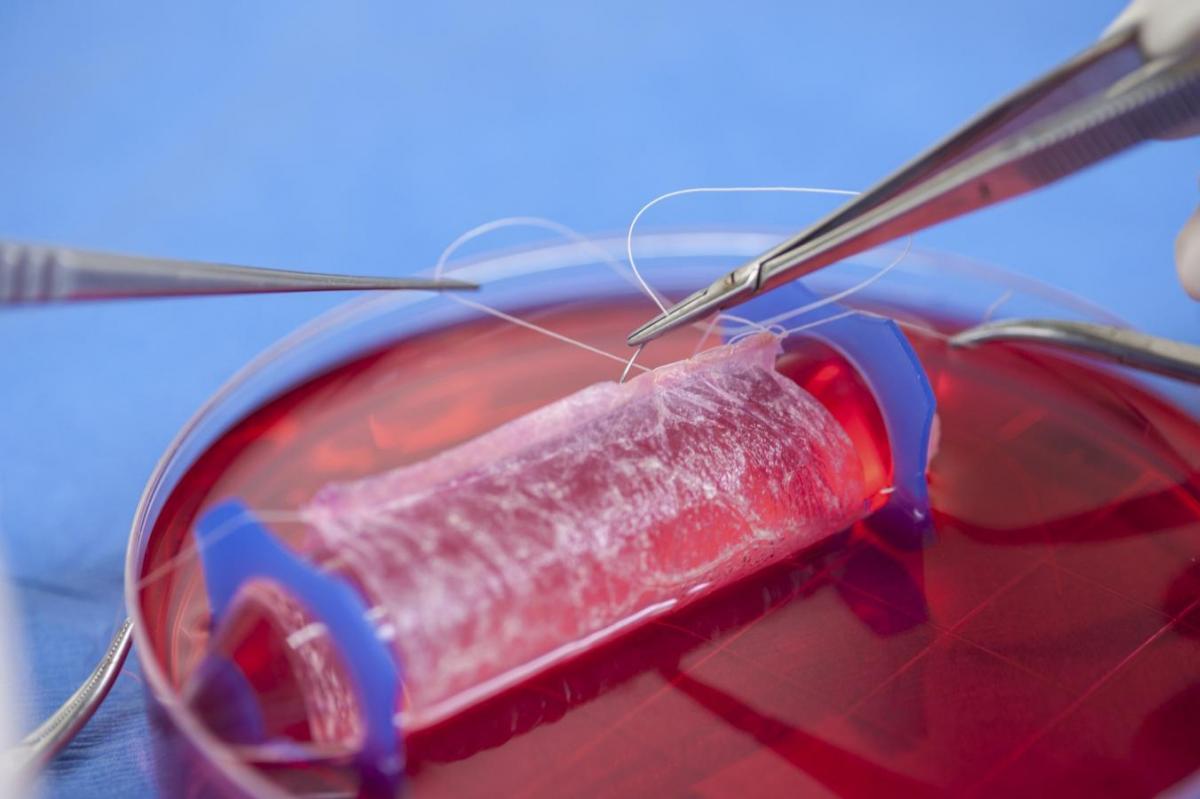

Uterine transplants are still in their infancy, so to speak; the first baby was born from a transplanted womb in Sweden in 2014.

These operations are not a dramatic shift from what has already been possible with reproductive technology over the past 10 years or so. Over the last couple decades, in-vitro fertilization (IVF) has become more common — some 210,000 women sought IVF treatment in the U.S. in 2015. It’s usually used for those who are having trouble conceiving a child the old-fashioned way. In IVF, a doctor removes eggs from the ovaries and fertilizes them in the lab to create embryos that the doctor can then insert into a healthy uterus.

IVF is expensive (a single treatment can cost $12,000 to $35,000, depending on the the recipient’s age and health), but it’s appealing for people struggling to get pregnant due to ovulation disorders, uterine fibroids, a partner’s low fertility, or unexplained infertility. Some queer couples also use IVF to get pregnant via a sperm donor or surrogate. Scientists have also figured out how to create embryos using genetic material from two mothers and a father, and they’re working on the possibility of two-father babies (though even attempting that is still at least a few years out).

In a survey, nearly one in three obstetrician

gynecologists said they believe uterine transplants are unethical.

Still, there seems to be a growing demand, from cisgender women and trans women alike, to bring uterus transplants to a larger population. For the next few years at least, the experimental operation is limited to cisgender women with unhealthy uteruses, or who were born without them. The procedures so far have implanted uteruses from living and deceased donors into otherwise healthy recipients. Once the uterus is fully integrated into the body, doctors insert embryos fertilized via IVF; the procedures so far have used the patient’s own eggs.

It’s an invasive, and still somewhat experimental, procedure: both the recipient and the donor undergo invasive surgeries that come with risks, and the recipient takes immunosuppressant drugs to keep her body from rejecting the organ. It’s one of the few transplant procedures that’s not intended to be permanent or life saving; the transplanted uterus can be used for one or two pregnancies and is removed after about four years. Sometimes the transplant is rejected, and pregnancies accomplished in this way have all been high-risk.

There’s a lot of questions about whether such an operation is necessary at all.

“A lot of people have questions about whether this is a valid allocation of health care resources,” says Megan Allyse, a bioethicist at the Mayo Clinic. Uterine transplants involve an operation on at least one, sometimes two otherwise healthy people — many transplant surgeons believe they should only do such invasive procedures on someone who is sick, and for lifesaving purposes.

And although there’s clearly a demand for this surgery, not everyone agrees that the desire to carry a baby falls into the category of medical necessity; in one recent survey of over 400 obstetrician-gynecologists, nearly one in three said they believe uterine transplants are unethical. Allyse says infertility is neither life-threatening (though it’s categorized as a disease by the World Health Organization) nor does it pose any known long-term risk to physical health, though it can certainly cause mental distress. When medical ethicists consider a $300,000-$500,000 operation (how much a uterine transplant might cost when it becomes more widely available, according to Allyse), and the research to develop it, they also consider other needs those resources could be going to instead.

There are other ethical concerns. Some fear that women may feel compelled — by their partners or families, or from society in general — to carry children. And then there’s the question of who gets to give and receive a womb, and whose needs should be prioritized. Right now, international law prohibits the sale and purchase of organs; in the U.S., there are also strictly-organized donor lists and psychological screening for donors and recipients. No such systems exist for uterus transplants yet, as the procedure is so new.

In a very hypothetical future in which none of these safeguards exist for uteruses, and in which unethical zealots are running things, Allyse says, people might end up with little choice about donating or receiving a uterus. “You’re looking at something like a Handmaid’s Tale scenario,” she says.

Trans Medicine Under The Knife

The well-publicized uterine transplants conducted over the past few years in the U.S. and in Europe have been limited to cisgender women. But some have been tried on trans women in the past. In 1931, a trans woman received one of the world’s first uterine transplants and died from complications, as this was long before immunosuppressants made organ transplantation viable (her story was the subject of the recent film The Danish Girl).

In a future in which uterine transplants are commonplace, it’s not clear whether transgender women would make it to the top of the list to receive a donated uterus. Over the last 50 years, trans medicine has gradually become less marginal, with more research to show the positive effects of treatments such as hormone therapy and gender-related surgeries. As the interventions have matured, so has the rationale for using them.

Arguments in favor of gender confirmation surgery have often hinged on the slippery concept of medical necessity: healthcare services appropriate for the condition as determined by doctors, health insurers, and federal and state legislation. Transgender people are still woefully under-researched in almost all areas of medicine, in part because sample sizes for studies have often been minuscule. Even so, the studies that do exist have shown that trans people’s mental health is improved by access to hormones and gender-confirming operations, adding weight to the argument that doctors should prescribe hormones and surgeries, and insurers should cover them.

In the future, trans women who want a womb would likely argue that the procedure would improve their mental health and help complete their transition to womanhood.

But the current framework for trans health is already outdated, says Eric Plemons, an anthropologist at the University of Arizona and the author of The Look of a Woman: Facial Feminization Surgery and the Aims of Trans- Medicine. When gender confirmation surgeries were first performed 50 years ago, they were based on trans people’s desires, but also on the cultural belief that your gender and your genitals must always be aligned. “The idea has been that what a trans person needs from medicine is to transform their sex, defined as genital or reproductive anatomy category, from one binary sex into the other,” Plemons says.

The focus on genital surgery is gradually shifting, and his research shows that, while genital surgeries may be important to some people, many transgender people are equally or more concerned with changes that allow them to be perceived and treated as the gender they identify with. In other words, a surgery that’s considered “cosmetic” might actually be more psychologically important.

Plemons studies facial feminization surgery, a series of operations for trans women that typically involves reshaping their noses, cheeks, brows, and lips to appear more feminine. Along with laser hair removal and hormone therapies, many trans women say facial feminization is a priority for them because of its immediate effect on how people see them. “Listening to trans patients, genital surgery may not be what’s most transformative for them,” Plemons says.

…Genital surgery may not be what’s most transformative for [trans patients].

Surgeries like facial feminization and breast implants, which have a direct effect on how trans women are seen in the world, are still considered cosmetic by most doctors and insurance companies, and they do not fall into the category of medical necessity. To this end, it’s not yet clear whether uterine transplants would ever be categorized as a medical necessity for trans women.

Gender theorists and some activists have also begun to argue that sex itself is socially constructed. Many people (an estimated one in one thousand) are born intersex, with ambiguous genitalia or chromosomes. Right now, intersex people are still routinely put through nonconsensual surgeries as children so that their genitals conform to a binary sex designation. Many intersex adults have fought against these surgeries — they want to allow intersex kids choose their own gender, or maintain an ambiguous sex if they so choose. Transgender people also often live in bodies that are a mix of male and female traits, complicating the argument that a particular procedure is a “medical necessity.” In a way, advocates are pushing for a more diverse menu of options for trans people based on a rapidly changing theory of gender and sex.

How can, or should, medical procedures keep pace with these rapidly advancing conversations?

If biological sex itself is less binary than our society has led us to believe, surgery could represent endless possibilities. Babies carried by male-assigned people are only the beginning. Plemons says plastic surgeons are already considering whether they should construct ambiguous genitalia for trans people who request it — for example, some transgender men who get a penis via phalloplasty, which creates a penis through skin grafts, may want to keep their vaginal opening.

New technology could certainly bolster the surgical possibilities for trans people. Right now, trans men have the option of mastectomies or breast reduction, hysterectomies, and phalloplasty. Trans women can undergo facial feminization, receive breast implants, remove one or both testicles (orchiectomy), or have a vaginoplasty, which uses skin and tissue from the woman’s own body to create a vagina. Most current research is focused on improving the safety and efficacy of these operations — for example, some surgeons now use the Da Vinci robot, a robotic surgery tool, to perform genital surgeries because the robot can operate with more precision than a human hand. And biomedical engineers are working to create implants of all kinds that better imitate the human body in order to construct realistic breasts, vaginal canals, vulvas, clitorises, penises, and testicles.

Stem cell research could even more dramatically alter the ways we can update and adapt our bodies, gender-related or otherwise. Scientists know how to use a person’s cells to grow and shape new organs in the lab that can eventually be implanted. A lab at Wake Forest University in North Carolina has done vaginal and urethral implants already; the project’s lead doctor, Anthony Atala, says the lab is currently researching how to create 30 different organs, such as bladders and tracheas. To grow these organs in the lab, scientists need original tissues from the person receiving the implant to reduce the risk that the patient’s body will reject the organ. Collagen scaffolding guides the shape into which the organs grow. Atala’s experiments with lab-grown organs require more study of the long-term effects, but they could become more widely available soon.

To Caleb Wilvich, these developments are very exciting. “If I could wave a magic wand, it would be possible to not only transplant a uterus, but have a transplant body part exchange, where people who didn’t want their uterus or vagina or penis or breasts for various reasons, including trans identity, would be able to give those body parts to another person.”

The Future Is Transmorphological

As researchers develop more techniques to alter the human body according to a person’s desires, the procedures will likely become even safer. People could alter their bodies more easily and more frequently, which might also mean pushing the body into new shapes and structures. “Is it good to have unlimited constant body modification in search of a potential best self? I don’t think there’s a single answer to that question,” says Plemons. “That’s partly based on how we define what’s wrong with people.”

Valkyrie Ice McGill, a transgender woman and self-identified advocate of “morphological freedom,” loves the idea of constant body modification in search of a best self. She says when she looks in the mirror, she sees a four-foot-eleven pixie with horns and hooves — a demonic feminine succubus. In reality, McGill says, she’s male-assigned, six-and-a-half feet tall, and hairy “like a gorilla.” Morphing her own body has been a lifelong dream, one that’s led her to the outer edges of fantasy about how the human body could be changed by technology.

“We can rebuild every part of the human body: teeth, bone, just about anything,” she says excitedly. “What we don’t know how to do at the moment is put all of this together into one single cohesive piece: the Da Vinci surgeon robot that takes a 3D map of your body and then plans a series of microsurgeries to slowly transform you from one thing to another.”

That’s what she means by “morphological freedom” — the ability to transform what she calls “vanilla human” forms into those with cloven hooves, wings, pixie ears, different bone structures. Her vision is a radically different idea of how things play out in the genetic lottery, a sort of surgical libertarianism: at some point, we grow up, and get to take whatever form we want. “I tend to be on the extreme side,” she concedes — she doesn’t know of any physicians who agree that pushing the human form in this way is likely, or ethical.

For now, McGill’s daydreams about changing form aren’t currently possible. She can’t even afford hormone therapy, which she would have to pay for out of pocket. She spends a lot of time on Second Life, a virtual reality game in which you get to choose and design an avatar. So for her, maybe daydreaming about the future —in which sex or gender is fluid, and species itself is mutable — isn’t an ethical quandary, but a way out of her present reality.

“If I’m completely miserable being a six-and-a-half-foot-tall NFL linebacker looking like a gorilla, and I’d much rather be the cute happy-go-lucky succubus that I am on Second Life, why is it anyone’s business?” McGill says. “I’m not out to hurt anybody. This is all about me being able to look in the mirror and not want to scream.”

Disclaimer: the editor of this piece was a recipient of the Mayo Clinic’s 2017 journalist residency for surgery, where she met one of the sources quoted in this piece. The residency was paid for by the Mayo Clinic; however, neither the clinic nor any of its affiliates has editorial review privileges.