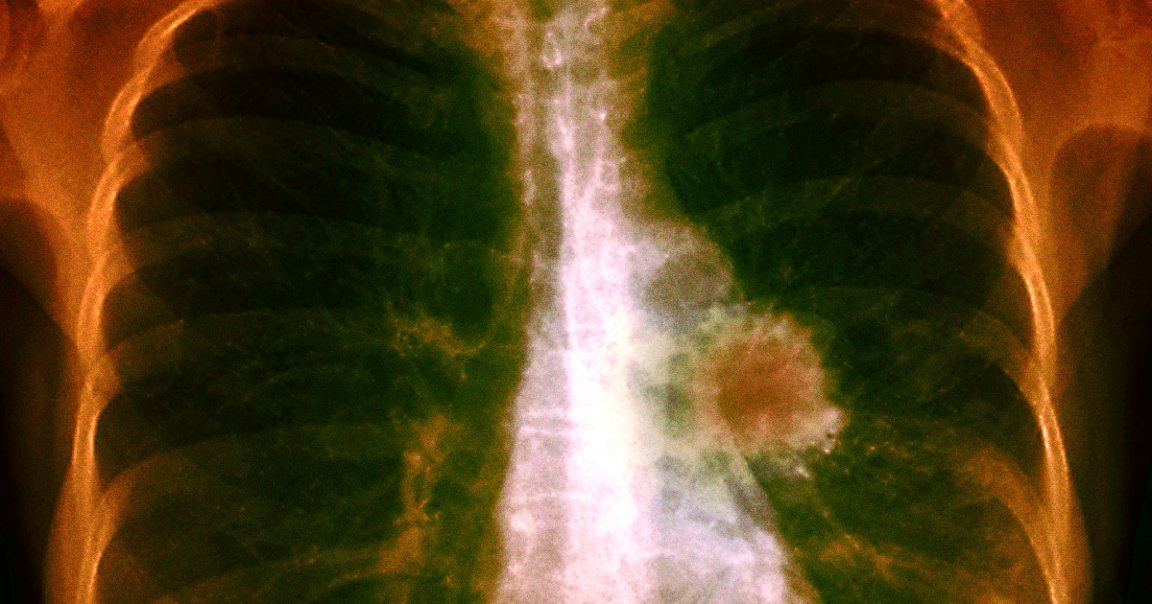

In a development that scientists have reportedly called “thrilling” and “unprecedented,” a decade-long global study has shown that a once-daily pill reduces the risk of dying from lung cancer by over half.

Taken after tumor-removal surgery, the drug, known as osimertinib, was shown in the study — published Monday in The New England Journal of Medicine — to lessen the risk of patient death by 51 percent worldwide. As it probably goes without saying, that’s a huge deal — and researchers certainly aren’t taking it lightly.

“Thirty years ago, there was nothing we could do for these patients,” Roy Herbst, the deputy director of Yale Cancer Center and lead author of the study, told The Guardian. “Now we have this potent drug.”

“Fifty percent is a big deal in any disease,” he added, “but certainly in a disease like lung cancer, which has typically been very resistant to therapies.”

To study the potential impacts of the drug, researchers enrolled roughly 682 non-small cell lung cancer patients — non-small cell cancer being the most common form of the lung disease — from 26 countries worldwide, all aged between 30 and 86 years old. Of those hundreds of patients, 339 randomly received the AstraZeneca-made osimertinib pill, while 343 were given a placebo.

Ultimately, study results revealed that after five years, the non-placebo group observed a survival rate of 88 percent. That’s a resounding success compared to the placebo group, which saw a markedly lower survival rate of 78 percent.

“It is hard to convey how important this finding is and how long it’s taken to get here,” Nathan Pennell, an expert at the American Society of Clinical Oncology who was not involved with the study, told the Guardian. “This shows an unequivocal, highly significant improvement in survival.”

Importantly, as the Guardian notes, everyone in the trial had a mutated EGFR gene, a mutation present in roughly a quarter of lung cancer cases worldwide. It also tends to be present in lung cancer patients who have never or rarely smoked, and is also more common in women than men. And on that note, per the Guardian, about two-thirds of the lung cancer patients enrolled in the successful trial were women.

But as the scientists emphasized to the Guardian, it’s not yet standard practice for lung cancer patients to be tested for EGFR mutations.

The study findings “further [reinforce] the need to identify these patients with available biomarkers at the time of diagnosis,” Herbst told the newspaper, “and before treatment begins.”

“A five-year overall survival rate of 88 percent is incredibly positive news,” Angela Terry, chair of the lung cancer charity EGFR Positive UK, told the Guardian. “Having access to a drug whose efficacy is proven and whose side-effects are tolerable means patients can be confident of and able to enjoy a good quality of life for longer.”

More on cancer treatments: Virus Modified to Kill Cancer Cells Appears to Have Saved a Patient’s Life