A team of scientists has grown “minibrains” in a lab, with the eventual goal of linking them together to form super-efficient “biocomputers.”

In a new paper published in the journal Frontiers in Science, a team of researchers laid out a roadmap to achieve that goal, a new multidisciplinary field they’re calling “organoid intelligence,” or OI for short.

Coining the new term is meant to “establish OI as a form of genuine biological computing that harnesses brain organoids using scientific and bioengineering advances in an ethically responsible manner,” the paper reads.

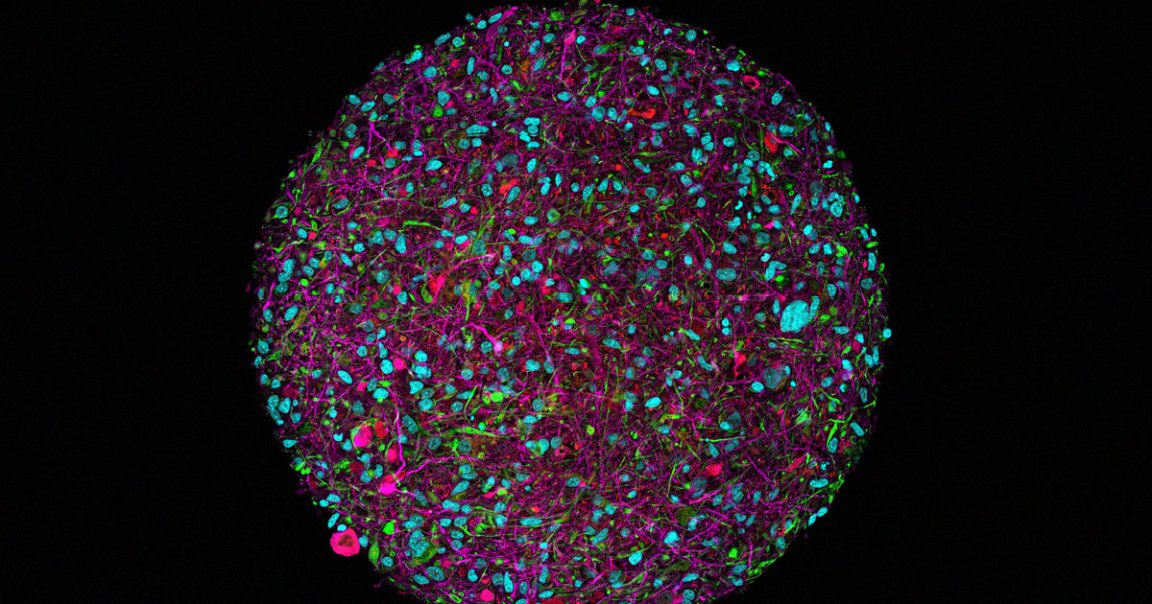

Biocomputers made up of minibrains or organoids, small 3D structures made up of stem cells that are designed to mimic the brain’s shape and ability to learn, could represent a huge leap in computing power.

“While silicon-based computers are certainly better with numbers, brains are better at learning,” said John Hartung, corresponding author and professor of microbiology at John Hopkins University, in a statement.

Hartung used a simple analogy to contrast the approaches.

“For example, AlphaGo [the AI that beat the world’s number one Go player in 2017] was trained on data from 160,000 games,” he added. “A person would have to play five hours a day for more than 175 years to experience these many games.”

Thanks to its incredible ability to store information and learn far more energy efficiently than conventional computers, there’s “an enormous power difference compared to our current technology” between the human brain and a conventional computer, Hartung argued.

Scientists have already successfully taught minibrains how to complete simple tasks. For instance, in 2021, scientists managed to teach a number of organoids to play the video game “Pong.”

More recently, a team of researchers at the University of Pennsylvania successfully inserted human neurons into the brains of rats with damaged visual cortices to partially restore functionalities of these damaged areas of their brains.

But before we can build superbrains out of tiny organoids that can efficiently complete complex tasks, scientists still have a lot of work to do.

The lab-grown minibrains, often referred to as brain organoids, are simply far too small and would have to be scaled up from around 50,000 cells each to at least ten million, Hartung explained.

In addition to efforts to scale them up, the researcher and his colleagues are working on new ways to have the organoids communicate with each other, which means they have to pass on the knowledge they gained by expressing it in some way.

“We developed a brain-computer interface device that is a kind of an EEG cap for organoids, which we presented in an article published last August,” Hartung said in the statement. “It is a flexible shell that is densely covered with tiny electrodes that can both pick up signals from the organoid, and transmit signals to it.”

While the field of organoid intelligence has only begun to scratch the surface of what’s possible, the scientists involved are excited about the possibilities. For instance, we could one day grow personalized brain organoids to help patients suffering from neural disorders such as Alzheimer’s, or test “whether certain substances, such as pesticides, cause memory or learning problems,” as Hartung suggests.

“From here on, it’s just a matter of building the community, the tools, and the technologies to realize OI’s full potential,” he added.

More on minibrains: Blobs of Human Brain Implanted in Rat Brains Replace Damaged Vision Functionality