In May of 2014, the journal Vaccine published an article by the University of Sydney which confirms that there is no association between vaccines and autism (or between vaccines and the autism spectrum disorder). Although this information is not new, as scientists have known for a long time that there is no link between vaccines and autism, the study is notable as it examined seven sets of data involving more than 1.25 million children.

It concluded that there was no evidence to support a relationship between vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough and the development of autism.

To repeat (because honestly, we can’t repeat it enough), there is no link between the MMR and autism, between ADS and autism, or between any vaccine and autism. None.

Of course, as is true of all things, vaccines do harbor some risks. They can cause rashes or other allergic reactions, but such instances are exceedingly rare (far rarer than the number of people that contract these illnesses without vaccines). Ultimately, that is the important thing to remember.

Vaccines save lives.

For example, smallpox is one of the deadliest known diseases, plaguing humanity for thousands of years. Researchers believe that it first emerged in human populations around 10,000 BCE. Although the overall death toll is unknown, in the 20th century alone it killed over 300 million people. In 1967, the World Health Organization estimates that smallpox killed an estimated 2 million people worldwide. And keep in mind, this is just one virus over the course of one year. Ultimately, the total number of people killed by viruses is simply staggering.

Today, no one dies of smallpox. Not one person. It was eradicated by vaccinations. The last natural occurring case was in 1977.

Sadly, people aren’t getting vaccinated. And there has been an increase in measles cases in the United States. The Center for Disease Control reports that there were 102 cases in January of this year, most stem from one outbreak (which occurred in Disneyland). All it takes is one person. Just one.

Some say that we should not worry. That people who are vaccinated are protected, so who cares? If people don’t want to get vaccinated, let them. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. There are many people who can’t get vaccinated because they are too young or have certain allergies. Moreover, each time someone gets an illness, there is a chance that it will mutate, which may make vaccines less effective. Others would say that 102 cases is not that much. But when such things are entirely preventable, 1 case is too much, as the below letter reveals.

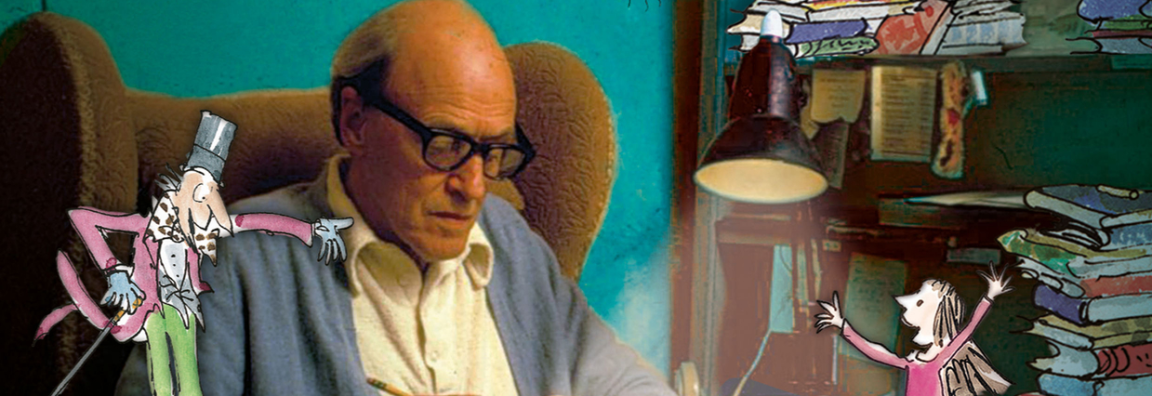

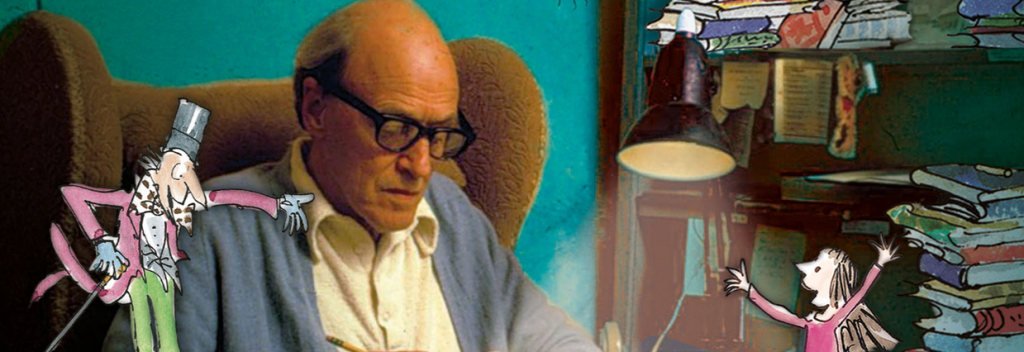

This is a statement about the impact of Measles. It was written by children’s literature author Roald Dahl, who lost his daughter in 1962. He wrote this letter to parents in 1988.

Olivia, my eldest daughter, caught measles when she was seven years old. As the illness took its usual course I can remember reading to her often in bed and not feeling particularly alarmed about it. Then one morning, when she was well on the road to recovery, I was sitting on her bed showing her how to fashion little animals out of coloured pipe-cleaners, and when it came to her turn to make one herself, I noticed that her fingers and her mind were not working together and she couldn’t do anything.

“Are you feeling all right?” I asked her.

“I feel all sleepy,” she said.

In an hour, she was unconscious. In twelve hours she was dead.

The measles had turned into a terrible thing called measles encephalitis and there was nothing the doctors could do to save her. That was twenty-four years ago in 1962, but even now, if a child with measles happens to develop the same deadly reaction from measles as Olivia did, there would still be nothing the doctors could do to help her.

On the other hand, there is today something that parents can do to make sure that this sort of tragedy does not happen to a child of theirs. They can insist that their child is immunised against measles. I was unable to do that for Olivia in 1962 because in those days a reliable measles vaccine had not been discovered. Today a good and safe vaccine is available to every family and all you have to do is to ask your doctor to administer it.

It is not yet generally accepted that measles can be a dangerous illness. Believe me, it is. In my opinion parents who now refuse to have their children immunised are putting the lives of those children at risk. In America, where measles immunisation is compulsory, measles like smallpox, has been virtually wiped out.

Here in Britain, because so many parents refuse, either out of obstinacy or ignorance or fear, to allow their children to be immunised, we still have a hundred thousand cases of measles every year. Out of those, more than 10,000 will suffer side effects of one kind or another. At least 10,000 will develop ear or chest infections. About 20 will die.

LET THAT SINK IN.

Every year around 20 children will die in Britain from measles.

So what about the risks that your children will run from being immunised?

They are almost non-existent. Listen to this. In a district of around 300,000 people, there will be only one child every 250 years who will develop serious side effects from measles immunisation! That is about a million to one chance. I should think there would be more chance of your child choking to death on a chocolate bar than of becoming seriously ill from a measles immunisation.

So what on earth are you worrying about? It really is almost a crime to allow your child to go unimmunised.

The ideal time to have it done is at 13 months, but it is never too late. All school-children who have not yet had a measles immunisation should beg their parents to arrange for them to have one as soon as possible.

Incidentally, I dedicated two of my books to Olivia, the first was ‘James and the Giant Peach’. That was when she was still alive. The second was ‘The BFG’, dedicated to her memory after she had died from measles. You will see her name at the beginning of each of these books. And I know how happy she would be if only she could know that her death had helped to save a good deal of illness and death among other children.