Junk DNA

What can the genomes of dolphins, elephants, and squirrels tell us about our capacity to resist diseases? Plenty, according to a new study published today in Cell Reports.

Some 98 percent of the mammalian genome doesn’t code for proteins. Instead, this region controls where and when the body expresses genes. Scientists at University of Utah Health (U of U Health) investigated this portion of the genome in various animals to find out more about its effect on health and disease response.

“People used to call the noncoding regions ‘junk DNA,’ but I see it as a jungle that has not been explored,” said paper co-author Christopher Gregg, an assistant professor of neurobiology and anatomy at U of U Health, in a university news release. “We are exploring the noncoding regions to try to discover new parts of the genome that might control different diseases.”

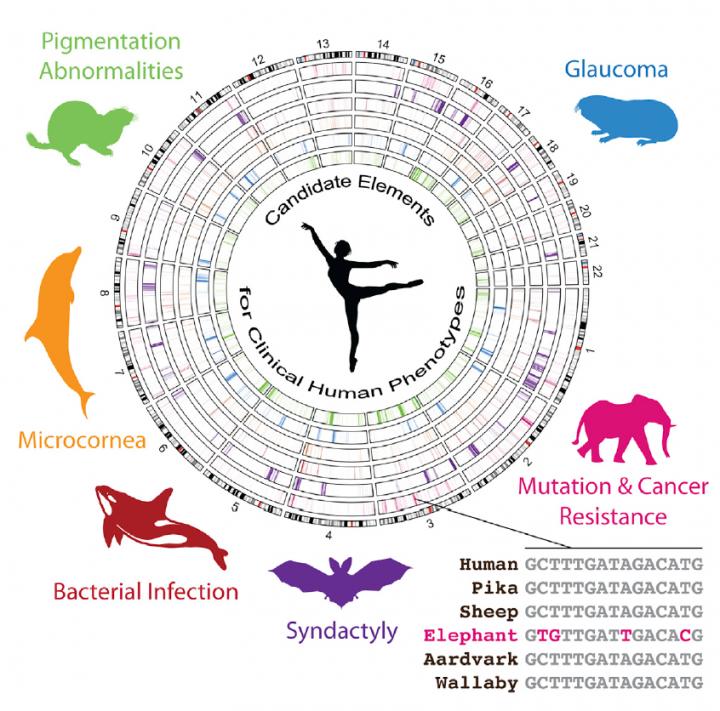

The researchers studied the genomes of African elephants, hibernating bats, orcas, dolphins, naked mole rats, and thirteen-lined ground squirrels for their research. They hoped that identifying rapidly evolving parts of the animals’ noncoding regions might offer up clues about how the human genome responds to different diseases.

“What we’ve done is use animals with extraordinary traits to reveal new elements in the human genome that we think are important, but were hidden to us before,” said Gregg in a press release.

From Animals to Humans

The team’s efforts paid off.

Elephants rarely suffer from cancer despite having 100 times more cells than a human and living for 60 to 70 years. During their research, the U of U team identified three genes linked to the elephant genome’s rapidly evolving regions that help repair the animal’s cells and prevent mutation.

In further tests of blood samples, the scientists identified additional links between genes that respond to damage and these rapidly evolving regions. According to Gregg, this shed a light on potentially cancer-resistant elements in human genomes.

“The elephant results revealed noncoding sequences in the human genome that we predict may control gene activity and reduce the formation of mutations and cancer,” he said in the news release.

The study’s insights weren’t limited to cancer, either.

The team identified elements in the bat genome that could help us understand hand and foot abnormalities. The dolphin and orca genomes could shed light on blood clotting disorders and eye development, while the squirrel genome might inform our understanding of albinism and Leopard Syndrome. The naked mole rat research could tell us more about glaucoma.

As Gregg noted, “junk DNA” is still largely unexplored territory, and drawing an accurate map of its most promising landmarks is an important first step to exploring it. Next, researchers can focus on figuring out how to leverage these discoveries to improve human medicine.