Getting the bigger picture

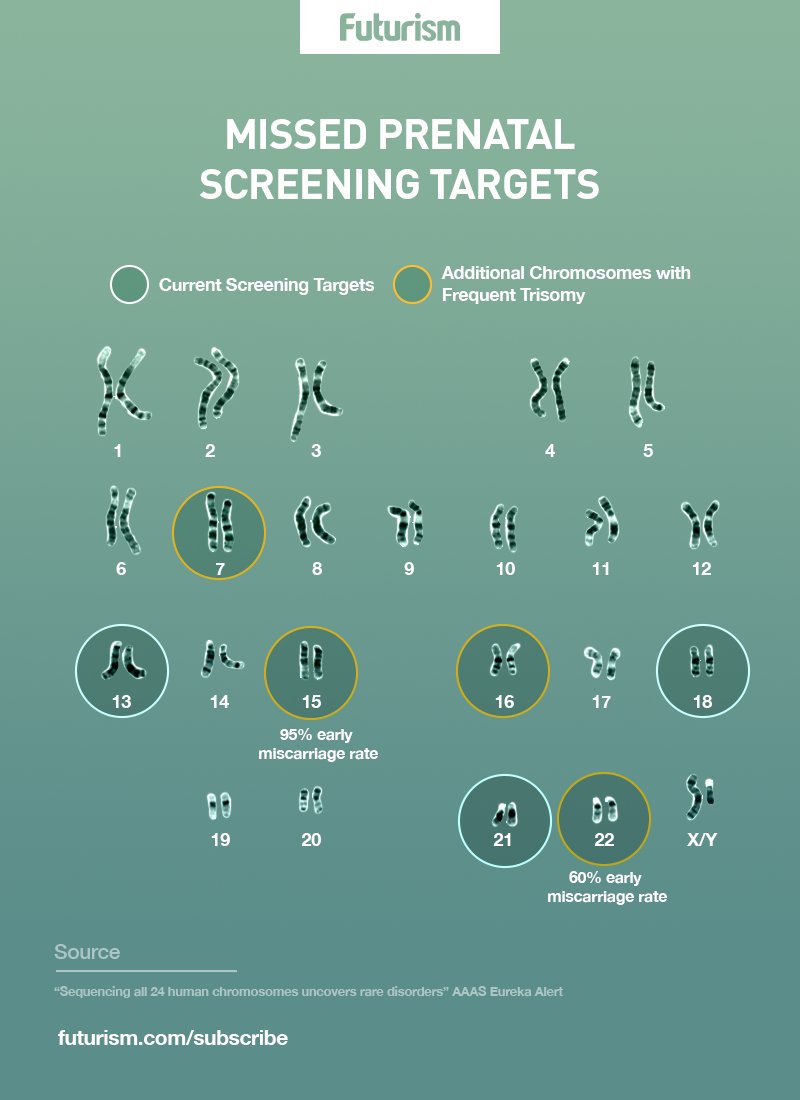

A new study from researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other institutions has revealed that including all 24 human chromosomes in noninvasive prenatal screenings can aid in the detection of genetic disorders that might explain abnormalities during pregnancy and miscarriage. Typically, genomic tests performed during pregnancy have only targeted extra copies of chromosomes 13, 18, and 21, and only rarely evaluated all 24 chromosomes. These new results may not only improve the accuracy of prenatal screenings, but also explain why some return false-positive results.

Although women frequently request noninvasive testing for genetic conditions during pregnancy, these tests generally only focus on common trisomies. “Extending our analysis to all chromosomes allowed us to identify risk for serious complications and potentially reduce false-positive results for Down syndrome and other genetic conditions,” NIH National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) chief of the Prenatal Genomics and Therapy Section and study senior author Diana W. Bianchi, M.D., said in a press release.

Secrets of less common trisomies

Using almost 90,000 samples of maternal plasma, the investigators analyzed DNA sequence data from US and Australian cohorts. For each cohort, researchers calculated the likelihood that any given sample has the typical two copies of each chromosome, called the normalized chromosome denominator quality (NCDQ). Samples with an NCDQ of 50 or below were flagged and evaluated further. In the US cohort, about 0.45 percent were flagged, compared to about 0.42 percent in the Australian cohort.

The researchers then looked at outcome data for the pregnancies. They were able to link 22 samples with early miscarriages, including all but one of the trisomy 15 samples and 3 of the 5 trisomy 12 samples. This is especially notable since neither trisomy 15 nor trisomy 12 are typically included in prenatal screenings.

“We found that pregnancies at greatest risk of serious complications were those with very high levels of abnormal cells in the placenta,” Victorian Clinical Genetics Services head of reproductive genetics division and study co-first author Mark D. Pertile, Ph.D., said in the press release. “Our results suggest that patients be given the option of receiving test results from all 24 chromosomes.”