There’s more bad news for NASA’s Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft.

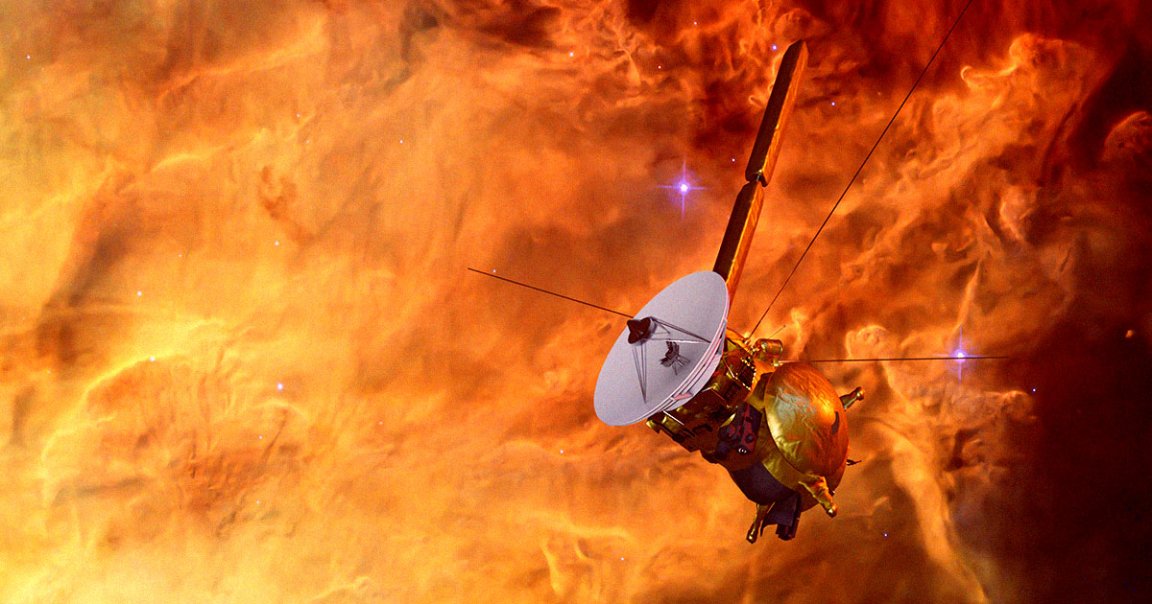

The twin space probes left the solar system in 2012 and 2018 respectively, and are currently over 15 billion and 13 billion miles from Earth.

And their energy sources, on-board radioisotope power systems, are decaying quickly, forcing the space agency’s Jet Propulsion Lab to shut down even more of the spacecraft’s scientific instruments.

According to a new statement, Voyager 1’s cosmic ray subsystem experiment was shut down last month, while Voyager 2’s low-energy charged particle instrument will be shut down before the end of March.

It’s yet another sign that the spacecraft, which have been blasting through space for almost half a century, are on their very last breath. NASA has already had to be extremely conservative with the available power.

The radioisotope thermoelectric generators, which use radioactively decaying plutonium-238 isotopes as a direct source of power, are losing roughly four watts of power each year, which means their days are numbered.

“The Voyagers have been deep space rock stars since launch, and we want to keep it that way as long as possible,” said JPL Voyager project manager Suzanne Dodd in the statement. “But electrical power is running low. If we don’t turn off an instrument on each Voyager now, they would probably have only a few more months of power before we would need to declare end of mission.”

The team has been focusing on the spacecraft’s scientific instruments that have been studying the solar system’s heliosphere, a protective bubble formed by the Sun’s activity that separates us from interstellar space.

Scientists were already forced to turn off Voyager 2’s plasma science instrument as a result of degraded performance back in October.

The spacecraft’s low-energy charged particle instrument, which will be shut down on March 24, has been relying on a stepper motor that’s already vastly exceeded the amount of activity it was tested for.

By the time it’s deactivated, according to NASA, the motor will have completed more than 8.5 million steps — compared to just 500,000 it was tested for in the 1970s.

“The Voyager spacecraft have far surpassed their original mission to study the outer planets,” Voyager program scientist Patrick Koehn explained. “Every bit of additional data we have gathered since then is not only valuable bonus science for heliophysics, but also a testament to the exemplary engineering that has gone into the Voyagers — starting nearly 50 years ago and continuing to this day.”

Scientists are eager to eke out as much life out of the spacecraft as possible — but power is quickly running out.

“Every minute of every day, the Voyagers explore a region where no spacecraft has gone before,” said Voyager project scientist Linda Spilker in a statement. “That also means every day could be our last.”

More on the spacecraft: The Voyager Probes Are Dying