Vanadium Dioxide

In science, there exists a law known as the Wiedemann-Franz Law that states, simply, that most metals that are good conductors of electricity are also good conductors of heat. This law essentially explains why things like motors and smartphones become hot when they’re used for an extended period of time.

However, one metal has been discovered to break this rule. Known as metallic vanadium dioxide (VO2), it’s seemingly capable of conducting electricity without the accompanying heat. VO2 is already a unique metal — it can switch between being an insulator and a conductor when heated to 67 degrees Celsius (152 degrees Fahrenheit) — but its diversion from the Wiedemann-Franz Law means that it could be ideal for a wider range of applications which other metals are not suited for.

The study that led to the revelation about VO2 was carried out by a team of scientists from the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and at the University of California, Berkeley back in January. The researchers were both surprised by and excited to witness this material’s unique capabilities.

“This was a totally unexpected finding,” said lead researcher and physicist Junqiao Wu, from Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division. “It shows a drastic breakdown of a textbook law that has been known to be robust for conventional conductors. This discovery is of fundamental importance for understanding the basic electronic behavior of novel conductors.”

Further Analysis

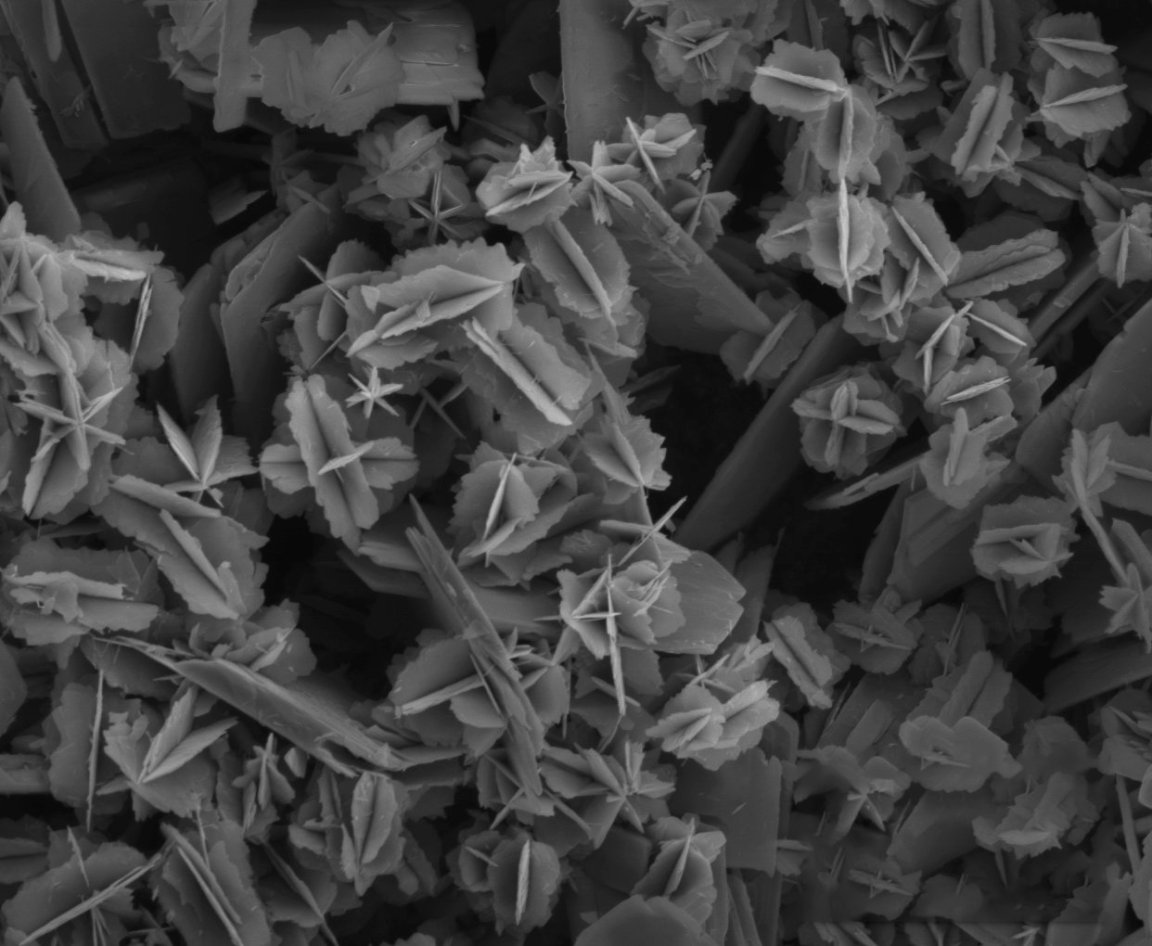

Wu and his team reached out to Oak Ridge National Laboratory Associate and Duke University professor Olivier Delaire to learn more about VO2. Using simulations and X-ray scattering experiments, their combined efforts enabled them to observe the material’s crystal lattice — known as phonons — and how its electrons move. Vanadium dioxide then revealed to the team that the thermal conductivity attributed to the electrons is ten times smaller than what the Wiedemann-Franz Law led them to expect. Furthermore, the electrons were moving in a manner similar to a fluid.

“The electrons were moving in unison with each other, much like a fluid, instead of as individual particles like in normal metals,” explained Wu. “For electrons, heat is a random motion. Normal metals transport heat efficiently because there are so many different possible microscopic configurations that the individual electrons can jump between.”

Wu added, “In contrast, the coordinated, marching-band-like motion of electrons in vanadium dioxide is detrimental to heat transfer as there are fewer configurations available for the electrons to hop randomly between.”

The surprises didn’t stop there. The team then discovered that the amount of electricity and heat VO2 can conduct can be adjusted when other materials are introduced. Adding metal tungsten, for example, simultaneously decreased the temperature at which VO2 would become metallic, and made it a better heat conductor.

“This material could be used to help stabilize temperature,” said Fan Yang, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry and co-lead author on the study. Yang went on to explain that more work and research would be required before vanadium dioxide could be commercialized and used in publicly available products.

That said, the team notes that VO2 has the potential to be used to remove, or at least reduce, the heat in engines, or to create a window coating that “improves the efficient use of energy in buildings.” Imagine being able to cool down a room without using any air conditioning or standing fans, or keeping the heat inside of a building during the Winter.

Of course, only time will tell if vanadium dioxide is up to the task. Regardless of the outcome, it’s interesting to learn how such characteristics exist in unsuspecting materials.