From the beginning of time, human progress has been driven by our need to understand how and why all things happen. The more we come to understand our surroundings, the deeper we desire to understand them further still. As our ancestors were presented with challenges, they innovated solutions using whatever knowledge and resources were available to them. When we think about how little our earliest ancestors had to work with, it seems all at once marvelous that they achieved anything at all, and almost somewhat boring — as the problems of the past seem so simple when examined through our present gaze, millennia in the future.

Even just a few generations ago, our parents and grandparents found the technology of The Jetsons and Star Trek to be fantastical and purely science fiction. Many of those clever gadgets — whether it be subservient robots or handheld computers — are already so commonplace as to be considered mundane by the newest generation. A generation that has never lived in a world with smallpox, or without an iPhone. As science and technology advance at seemingly warp speed, it may feel as though we know practically everything there is to know. Or, at least, that we are getting very close.

In an op-ed for Scientific American, physicist and author Daniel Whiteson implores us to not become complacent. To not be satisfied by all that we have come to know about the universe around us and within us and beyond us because there is still so much left to learn. “When we teach science to children,” Whiteson advises, “we should certainly describe what we do know, but there should also be a strong emphasis on what we don’t know, to inspire the next generation of explorers.”

What are, then, some of those things we don’t yet know that could serve as inspiration for the next Einstein or Curie? The next Stephen Hawking or Katherine Johnson?

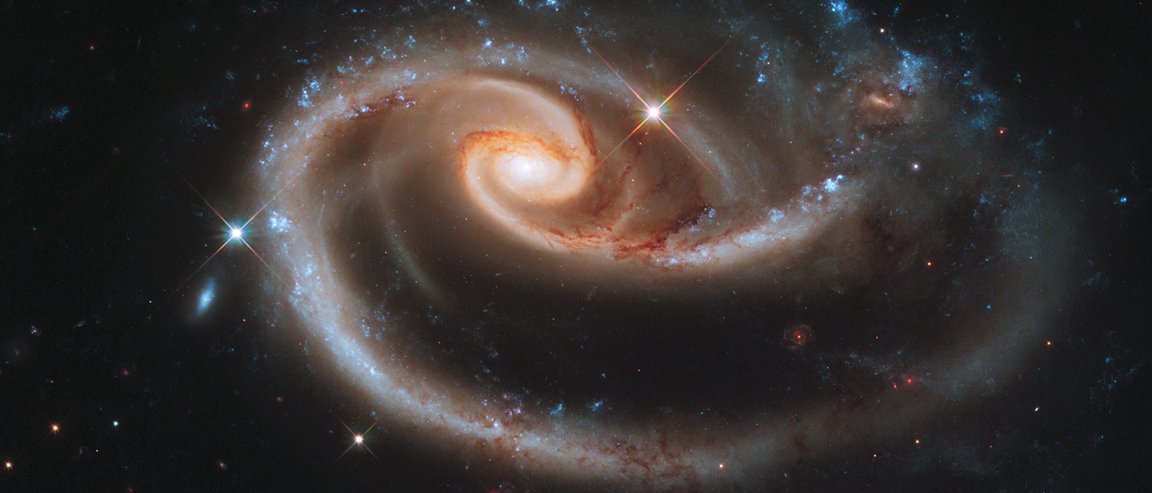

The Mystery of Dark Matter

One of the universe’s greatest tricks, a most profound irony, is that the very evidence that makes physicists and astronomers certain that “dark matter” exists also makes it nearly impossible for anyone to prove its existence. We don’t even recognize dark matter for what it is, because we don’t know what it is — we only register the impact it seems to have on gravity. In other words, we deduce that it’s real because we can see the effect it has on its surroundings. Kind of like a poltergeist moving furniture around in the dark.

[infographic postid=”66353″][/infographic]

The cosmic frustration of these elusive particles is made more challenging because those interactions are so infrequent that we’ve rarely witnessed them. It may also be that these particles are their own matter and anti-matter partners, rendering them invisible to us. And in fact, when it comes to thinking about dark matter, it isn’t simply one problem. The “problem of dark matter” is actually a bunch of problems that all must be solved — which is difficult when you’re not even sure what you’re looking for.

The Deep Blue Sea

As vast and therefore intriguing as the outer limits of our universe may be, here on Earth there are numerous mysteries left to be solved in our oceans. The entire landscape of the deep sea — the world underwater — is as varied as the one above: there are waterfalls, volcanoes, and even lakes, yet we have yet to truly explore the majority of them. And we understand even less about the creatures that live there. We may well understand the topography of the moon better than we do our oceans, strange as that seems. We’ve been looking up when perhaps it would have been just as interesting to look down.

In the deepest, darkest parts of the ocean there are species we’ve barely caught glimpses of and therefore have not thoroughly studied. It’s the stuff of legends — except it’s all real. The “final frontier” may not be the far reaches of space, but the unfathomable depths of our oceans.

The “Hard Problem” of Consciousness

One of the most fascinating, perplexing, and often frustrating unanswered questions is that of consciousness. The human brain continues to be one of the most question-filled foci of science and philosophy alike, and many of those quandaries are based in the question of what it means to be conscious. While we can glean some answers about brain function by using technology like MRIs, consciousness is far more nuanced than even our most refined medical imaging can detect. We know quite a bit about the structure and function of consciousness, but the feeling of it – and the why — have proven so subjective that the challenge of measuring them remains unsolved.

The paradox is that consciousness is, perhaps, the one human experience that each of us knows intensely and intimately — yet to explain it to someone else and have them understand it and share in it seems, at this point anyway, next to impossible.

Are Aliens Out There?

Considering how old and enormous our universe is, the expectation is that there simply must be other lifeforms out there. The question is, why haven’t we made contact with them? Potential solutions to this question, known as Fermi’s Paradox, include everything from “aliens exist and know about us, but think we’re boring and therefore aren’t bothering to say hi” to “aliens don’t know about us at all because we’re located in the universal equivalent to the boondocks.”

As technology advances and allows us to not only see into space farther and more accurately — largely in the form of advance telescopes and satellites — but also allows us to travel into space, if there’s life out there to be found (and that wants to be found), it seems reasonable to think we’ll get there eventually.

Where Did We Come From (And Where Are We Going?)

The question of evolution has plagued humanity since the beginning of time. Our desire to definitively know how we got to where we are now isn’t just important because we care about our own evolutionary history, but because it could give us incredible insight into where we’re headed as a species. It could also, potentially, reveal important information about how evolution could be altered.

It may be that the key to understanding some of the most pressing issues in health and medicine — such as cancer and other illnesses, regenerative medicine, and even longevity — could be lurking in our evolutionary development.

It may well be that these and other greatest mysteries of the universe may not be solved in our lifetime. But our grandparents likely never imagined living in a world where they could put a computer in their pocket or ride in a self-driving car. It may be that in our twilight years, we will try to remember what life was like before we met aliens, colonized Mars, or cured cancer.